2018 School Spending Survey Report

Listen Out Loud: Lou Reed Archive Comes Home to Lincoln Center

On March 2—which would have been Lou Reed’s 75th birthday—the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (NYPLPA) announced its acquisition of the late musician’s complete archives. The press conference, held at NYPLPA’s Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center, in Lincoln Center, touched off a two-week celebration showcasing Reed’s work, including displays of selected items from the archives at NYPLPA and the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, as well as several public programs.

Lou Reed's passport

Photo credit: Jonathan Blanc/The New York Public Library

REED, RECORDKEEPER

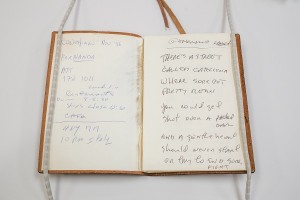

Notebook with lyrics

Photo credit: Jonathan Blanc/The New York Public Library

A HOME AT LINCOLN CENTER

NYPLPA was the team’s first choice for the archives’ home. After the Velvet Underground dissolved, Reed’s first solo show in the United States was at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in 1973. "It was kind of his welcome home show,” said Weiner at the March 2 event. “So we're really happy that on this occasion…Lou is once again welcomed into the hearts and minds of New York City through the Lincoln Center of the Performing Arts." Arrangements were finalized in December 2016, and paper and other non-audio materials were delivered to NPYL’s Library Services Center in Long Island City for processing. (Anderson has retained Reed’s equipment, guitars, and several boxes of awards, as that was outside the scope of what NYPLPA could accommodate. Most of the less iconic gear was auctioned off on eBay in 2014 to help finance work on the archives.) Jonathan Hiam, curator of NYPL’s American Music Collection and the Rodgers and Hammerstein Archives of Recorded Sound at NYPLPA, was excited about working with the collection from the start. Reed “was a consummate New Yorker,” he told LJ. “He was a lover of the library, and of course his artistic legacy fits squarely in with the types of materials we collect here." Anderson worked closely with NYPLPA throughout the accession process. "It was amazing to see the level of detail and focus that she put towards answering all the questions that had to be answered as we went along,” said Fleming. Processing the paper materials will take about a year, Hiam said; in addition to straightforward material such as receipts and contracts, there are thousands of photographs in which the subjects have not yet been identified. “And the fan art! Fan letters, of course, there are a ton of those and those are a blast. But also the gifts that people would send—photography, drawings, recordings...a sweater.”

Sweater knitted by fan

Photo credit: Lisa Peet

PLANS FOR THE ARCHIVE

The Lou Reed Archives team has further plans for the collection. Fleming is working with Anderson, Stern, Willner, and pop culture publisher Anthology Editions on a book featuring Reed’s personal essays, poems, and photographs from the archives. The volume will include an audio card with recordings of Reed reading his poetry, including his first major reading, in 1971, at the St. Marks Poetry Project. “It's still being developed,” said Fleming, “but that's the idea—to immediately start finding ways to make things out of this archive.” Another idea, still in the planning stages, is for a soundproof, contained room within the library where patrons could book time to listen to work by Reed—or any other artist—without headphones. "When we first visited the place, we asked them, 'Where do people get to listen to the music?' And they showed us the tables where they put on headphones,” Fleming recalled. “Immediately we [said], 'Is there somewhere in the building where there could be enough space to build out a little listening room with the highest tech gear like Lou would use to listen to stuff loud?' ” NYPL has been amenable to the idea, he told LJ, and he and Anderson are hoping to make the Lou Reed Listening Room a reality. "Over the next year…some of these other projects will begin to take better shape,” said Hiam. “Once we know everything that's in there and how to handle it, and we've done the preservation work we need to do, then we can start to see how it will fit into modes of access and wider projects." He hopes to see a larger exhibit drawing from the full archive sometime in the next few years, and predicts that the material received from Anderson’s team is not the full extent of what will eventually become the Lou Reed Archives. "Once the public sees an archiving project like this, a local hero come into the library...we start to get quite a few people contacting us to tell us ‘hey, I've got this,’ or ‘Lou Reed gave me this.’ So once an archive initially comes in, then there's this period where we start to...snowball,” Hiam told LJ. “People are excited to contribute and be part of this." Hiam is enthusiastic about the archives’ reception. “I don't think we really have anything here in music and recorded sound that's quite this size and scope, but because [Reed] had such an impact upon popular culture, I think there's going to be something for everyone.” Added Anderson at the March 2 event, “Lou had a cast of Shakespearean characters and wrote down what they said and what they might have thought. [His songs were] really many novels in short form. So I know he'd be so thrilled to be at the library."RELATED

RECOMMENDED

TECHNOLOGY

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!