Gaming History at the Strong National Museum of Play | Archives Deep Dive

When the Strong National Museum of Play opened its doors in 1982 in downtown Rochester, NY, it was built around the collections of Margaret Woodbury Strong (1897–1969), who had spent a lifetime collecting household objects—particularly those related to play, such as dolls and dollhouses. The museum’s initial mission was “to document everyday life in the northeastern United States between 1840 and 1940, which was essentially the impact of industrialization on the rising middle class.” In 2003, the museum refocused on play, play-centered objects, childhood, and education.

|

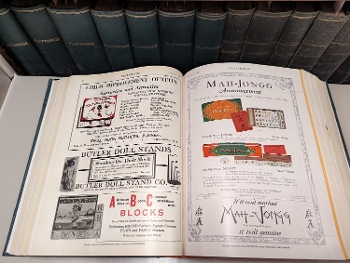

Mah-jongg spread from the September 1923 issue of PlaythingsCourtesy of the Strong Museum |

When the Strong National Museum of Play opened its doors in 1982 in downtown Rochester, NY, it was built around the collections of Margaret Woodbury Strong (1897–1969), who had spent a lifetime collecting household objects—particularly those related to play, such as dolls and dollhouses. She wanted her collection to become a public museum, but died before the dream could be realized.

However, Strong stipulated in her will that a board should be formed to establish a museum and decide its mission. The three original trustees appointed an additional three board members and hired experts from institutions such as the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and Colonial Williamsburg to assess the collection. They determined that its strength lay in Strong’s dolls and other toys. But, as Julia Novakovic, Strong Museum senior archivist, pointed out, “This was 1969. You [couldn’t] make a museum about dolls and toys.”

Instead, the museum’s initial mission was “to document everyday life in the northeastern United States between 1840 and 1940, which was essentially the impact of industrialization on the rising middle class,” according to its website. This turned out not to be a very compelling topic, and visitors did not often return. About $60 million of Strong’s estate had been set aside to support the museum in perpetuity, among 19 other legatees, but the Strong continued to explore ways to attract more guests.

In the 1990s, the museum began bringing in more family-oriented programming, including a Sesame Street exhibit and a mini-Wegmans Super Kids Market interactive exhibit. In 2003, the museum refocused on play, and “how it encourages learning, creativity and discovery,” said Novakovic.

The Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play, were part of the museum from its inception. The library and archive were named for Sutton-Smith (1924–2015) in recognition of his importance as a leading scholar of play, explained Vice President of Collections Christopher Bensch. Sutton-Smith then donated his collected works, papers, and personal library to the Strong, and they became a key part of the collection.

As the museum’s focus shifted to toys and other play-centered objects, childhood, and education, the archives deaccessioned holdings not in scope with the new mission. “Just in the last decade or so, [the library and archives of play] has really exploded,” Novakovic said. “We’ve gotten some really iconic collections.”

FROM ANALOG TO VIDEO GAMES

The archives contain 3,000 linear feet of physical archival materials and about a dozen terabytes of digital data, mostly from the latter half of the 20th century—although items include books of English fairy tales dating back to the 1600s.

The collection focuses on three main areas. The first is dedicated to the study of play and includes works from play scholars, educators, sociologists, historians, and multidisciplinary scholars, which the Strong began collecting after the mission shift in 2003. The collection includes “the research materials and writings of some of the foremost play scholars who have devoted their careers to exploring the substance, psychology, and social impact of play,” noted Bensch.

Artifacts of play make up the second main category. This includes materials from toy designers, and game inventors and records from toy and game companies. One section, the Play Generated Map and Document Archive (PlaGMaDA), includes maps, character sheets, drawings, and other material created for tabletop or roleplay games such as Dungeons & Dragons or Shadowrun. Tim Hutchings, the donor behind the PlaGMaDA papers, collected these materials from gamers, since most people tend to pack them away or throw them out after the game session is done. These ephemeral materials “tell us about how a [game] character evolved, or how your play improved,” Novakovic said. “Some things are just really beautiful and artistic.”

The third area, collections related to video and electronic game history, is the largest and most used part of the archives. It contains materials from major game companies, including the Atari Coin-Op Division, Atari’s remaining archives—some 600 linear feet of material that includes technical designs, documentation, memos, notes, photographs, marketing materials, and wiring diagrams from 1973 until the company closed in 2003.

The International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG) was established in 2008, making the Strong one of the first major institutions to collect video game history, Novakovic said. Iconic video games from the 1980s, such as Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? and Oregon Trail, are featured, as well as others developed by Sierra On-Line and Broderbund Software, plus materials from pinball game companies and papers from smaller companies and individuals. However, the Strong does not have materials from Nintendo, which is a common request from researchers.

Designers represented include Jordan Mechner, who revolutionized game animation. For the 1980s franchise Prince of Persia, he wanted people’s movements to be smoother and more realistic, rather than the jerky movements ubiquitous in 8-bit games at the time. He filmed his brother running, jumping, and climbing; printed the film frame by frame; and then hand painted each frame. Finally, he rotoscoped the images and programmed them into code.

The digital collection holds more than 46,000 trade catalogs from companies such as Playskool and Hasbro aimed at wholesalers, retailers and consumers; in 2018, the Institute of Museum and Library Services awarded the Strong a grant to digitize more than 2,000 pre-1960 catalogs. Oral history projects include the Women in Games Initiative and the Doll, Parker Brothers, and Mahjong oral history collections.

Other digital projects include papers from Parker Brothers, featuring George S. Parker’s diaries, and the diaries and papers of Sid Sackson, who designed more than 500 board games. He also consulted for game companies and corresponded with individuals like composer Stephen Sondheim, a fan who created his own games. In his prolific diaries, Novakovic said, Sackson noted every person he talked and all of the media he consumed. At the end of each year, he indexed his own diaries—a boon to curators and researchers.

Thanks to a National Archives grant, the Strong is working to digitize Sackson’s diaries. The 1963 to 1971 diaries have been fully transcribed, and another five years are open at any time for crowdsourcing.

Endangered media pose an ongoing challenge. Some games are formatted in media that are—or are on their way to being—obsolete, such as Betamax and floppy disks. Equipment that can use older media formats is expensive and requires special skills and knowledge.

The Strong archives have been used for a variety of projects, from histories of Monopoly to examinations of the ways historical events, such as World War I and II, are depicted in games. One man who owned his own arcade, wanted to replace artwork on one of the game cabinets and reached out to the Strong, which provided historical reference scans of the part he needed to recreate.

MISSING AND PROBLEMATIC STORIES

As wide-ranging as the archives are, there are “visible gaps in the collection,” Novakovic pointed out—notably, the lack of material detailing the contributions of women and people of color. It’s an institutional goal and effort. Bensch, Novakovic, and other members of the curatorial team have been actively working to establish relationships with Black, Latine, and Asian game and toy creators and hope to receive materials for the collection from game creators and designers of color.

She also acknowledged that some materials, such as the trade catalogs, can be a “real rollercoaster, because you’re going to see some awful stereotypes.” The Strong works to contextualize offensive works, Novakovic said, through display narrative explaining the items’ historical context.

The museum is also collecting more stories of the women behind the scenes in the video gaming industry. Since 2017, the Strong has been conducting the Women in Games initiative to gather oral histories and other ephemera from women in the game industries.

COME TO PLAY

As the majority of the Strong’s materials date from the latter half of the 20th century, much of them are still under copyright, limiting what can be digitized and made available online. Materials can be accessed on-site at the Strong, or for researchers who are unable to come in person, archives staff can answer questions or provide reference scans for a small fee.

For those who wish to visit the Strong, Novakovic recommended filling out a research request two weeks beforehand. Archives staff can for long distance scholars and provide reference scans.

In addition to the cultural and historical background, they provide, Novakovic said, the Strong’s collections are, above all, about the games people played growing up. “Our archives can be a lot of fun, and there is definitely something for everyone,” she added.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!