Across her first two novels, Yanagihara established a certain pain/pleasure dichotomy that was more than mere point-counterpoint; it reflected the symbiotic relationship between suffering and meaning—specifically found in our capacity to love—that is emotionally and thematically instructive to the stories Yanagihara seems compelled to tell. This remains much the case with her third novel, though in less explicit terms. Following the opera of miseries that was

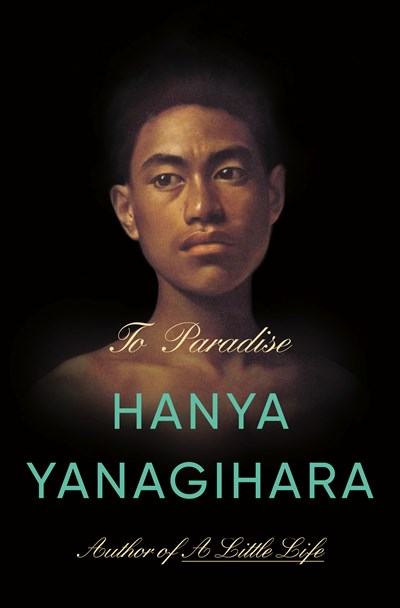

A Little Life, her latest is far more sedate, for better and for worse. To her credit, it is somewhat more clear-headed and certainly more conceptual, employing a three-act structure that jumps forward one century with each part, moving from the mansions and walk-ups of late 1890s New York City to mid-20th–century Hawai‘i to a near-future totalitarian state ravaged by perpetual pandemics. But while Yanagihara has faced accusations of miserablism and melodramatic hysteria, any indulgence here is cast instead toward establishing psychological and cultural acuity. She elongates each component part of her triptych narrative and excavates the crevices of character psyches with almost obsessive detail—something of an inverse of A Little Life’s swirling emotional tempest, though her patience with incident can border on paralysis at an unearned 700-plus pages. The narrative still impresses in spurts, particularly when it skews more erudite, but such littered pleasures are suggestive of an author at waypoint rather than destination, confidently forging new terrain but wandering too long in its unfamiliar territory.

VERDICT A distinct left turn for Yanagihara, one rooted in more mature social and psychological nuance but which the author is unequipped to support, either emotionally or formally, at its long-winded length.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!