Academic Libraries

When she was in college, Dr. Shamella Cromartie had a job at a public library where leadership and others were Black, which encouraged her to pursue a career in the field. “It’s important to see people that look like you in these positions so that you know that you can do it, too,” she says.

Many librarians lauded the development of Open Access (OA) publishing models, which offered, at least initially, to help solve the problem of an unsustainable and inequitable scholarly communications ecosystem while simultaneously addressing a growing interest in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). In the past year, the idea that, with appropriate guardrails, Artificial Intelligence (AI) can also play a role in changing scholarly communications has risen to the fore. But can OA, DEI, and AI ever live up to their promise of an affordable, equitable and sustainable publishing ecosystem?

Most libraries don’t own their own ebooks. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to LJ readers, yet it’s a statement that continues to confound elected officials and administrators who get an astounding amount of say in how much money public and academic libraries are allotted. This is one of the reasons I, along with my coauthors Sarah Lamdan, Michael Weinberg, and Jason Schultz at the Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy at New York University Law, published our recent report, The Anti-Ownership Ebook Economy: How Publishers and Platforms Have Reshaped the Way We Read in the Digital Age.

In Shavonn-Haevyn Matsuda's MLISc program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, she focused on examining and challenging inadequacies of access in information systems and library services. Later, after becoming head librarian at the University of Hawai‘i Maui College Library, Matsuda’s doctoral research investigated creating a system of information for Hawaiian archives and librarianship.

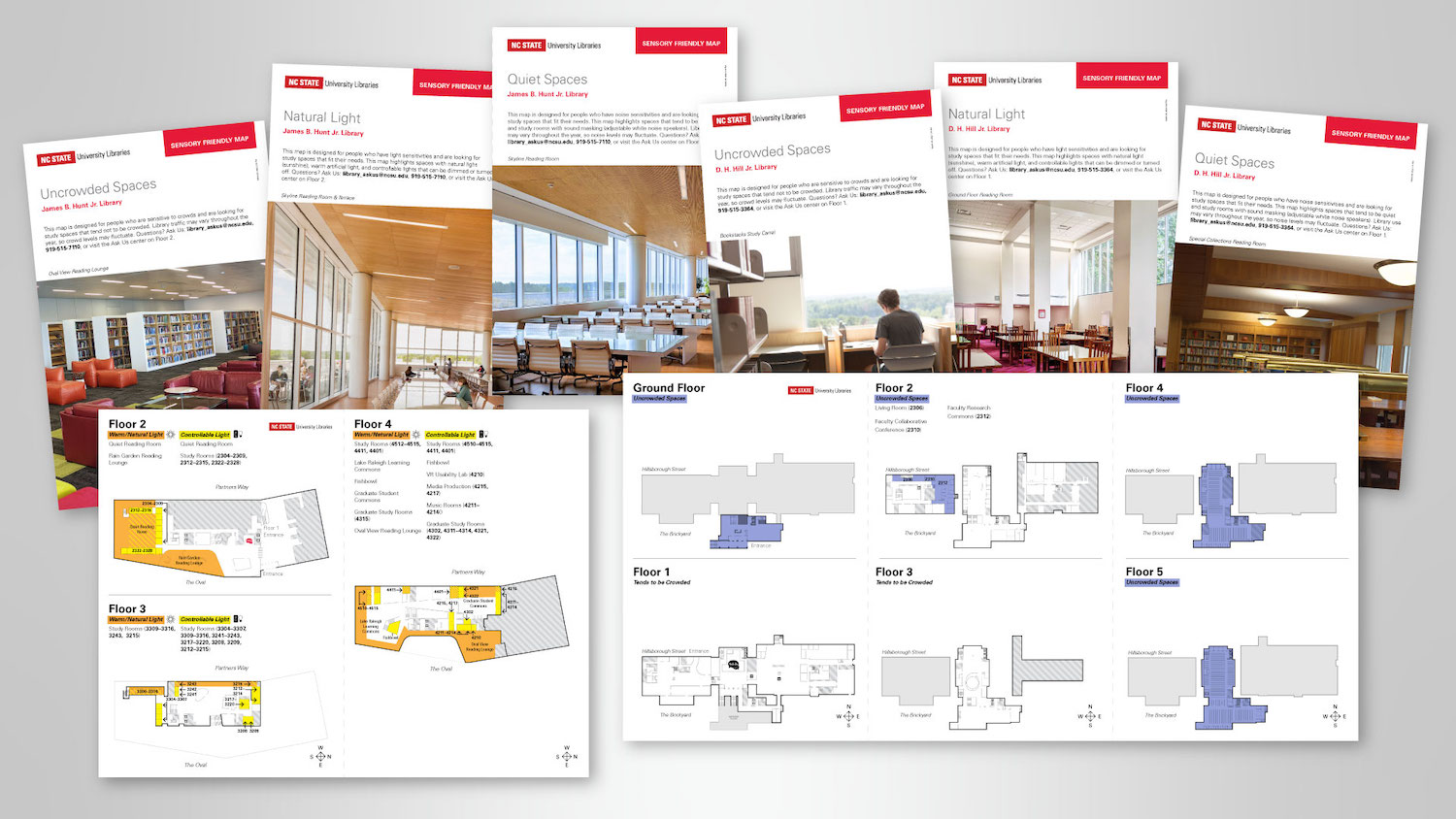

The need for increased accessibility is an ever-growing priority, as is understanding the scope and nuance of the concept. At North Carolina State University (NC State) Libraries, Raleigh, staff from a range of functional areas are working together to address and increase accessibility in their physical spaces, collections, and offerings. In May 2021 they formed an Accessibility Committee to coordinate and implement practices and changes throughout the system.

Professors and librarians at academic institutions sometimes describe certain students—or groups of students—as “not ready for college,” or assume that they “don’t know how to study” or are “at risk of dropping out.” These negative labels are most often given to students who are first-generation, low-income, and/or BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color). These views are called “Deficit Thinking”—blaming students for any failure to excel in a new, unfamiliar academic environment, rather than examining how an institution may be failing those students.

What do accessible spaces/programs/services look like in libraries? Ongoing engagement with disabled patrons and staff is key.

The latest report from Ithaka S+R, “Big Data Infrastructure at the Crossroads,” released December 1, offers critical findings and recommendations on the ways higher ed researchers, scholars, and technicians can partner with university and college librarians to support data research. The report was built from quantitative results and interview transcripts produced by a cohort of librarians at each participating institution.

On March 17, Ithaka S+R released results from its most recent survey of more than 600 academic library deans and directors across the United States. The report, “National Movements for Racial Justice and Academic Library Leadership,” looks at how their perspectives and strategies around diversity, equity, inclusion (EDI), and antiracism have changed over the last year, as well as their perceptions of COVID-19’s financial impacts on staff and faculty of color.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing