Related

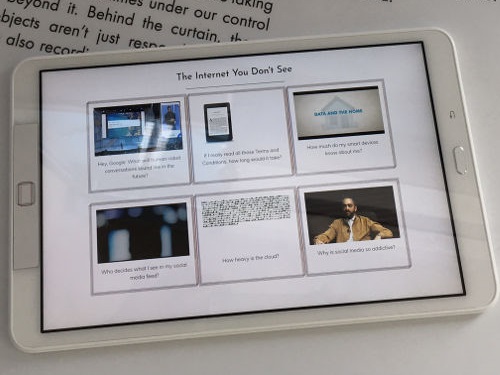

From January 2 through 18, the Nueces County Keach Family Library in Robstown, TX, is hosting the Glass Room Experience, a special exhibition designed to spark discussion about personal data and online privacy.

At the University of North Alabama, we are quite proud of the first-year library instruction sequence that was built through years of hard work, testing various ideas and components, and constant reflection and assessment.

First-year college and university students enter with widely varying levels of information literacy, particularly in light of the funding crisis that has left so many K–12 public schools without functioning school libraries and trained school librarians/media specialists. LJ recently set out to understand what information literacy instruction entering students need, what they’re getting, and what impact it has on their experience as first-year students.

I wrote recently that the rate of media illiteracy is the information crisis of our time (“Faked Out,” School Library Journal, 1/17, p. 6), but now that very real issue has nonetheless been trumped by a full-on deliberate assault on the flow of information—from journalism and scientific research to dissemination via social media and traditional channels. There is no such thing as an alternate fact, but there is certainly an alternate reality: a chilling, censorial, obfuscating one being offered as a threatening new normal by the new federal administration in the first days and weeks of 2017.

Heather Moorefield-Lang has witnessed the face of freshman terror when the first-year students walk into the college library at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, are confronted by two million books, and don’t know where to start. As an assistant professor at the School of Library and Information Sciences, she knows that relieving that angst is her job.

So many ideas can be sparked by coincidental juxtaposition. In the past few weeks, I have been thinking about the intersections between scholarly communications and information literacy. This was largely because I was part of a panel at the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Conference about the task force charged with implementing the 2013 White Paper on the topic. My specific task was to discuss how the new Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education illuminated the approach we called for in the white paper. On top of these concerns came the Blurred Lines copyright case, which was all over the media in the past few weeks, and about which I have been asked my opinion repeatedly. Can these different strands be woven into a coherent idea?

Now that the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education is finished, I finally got around to reading it. I was often critical of parts of the information literacy standards, but haven’t found much to criticize about the “Framework,” although I know others have. Most of the “threshold concepts” are things I’ve been talking about with students for years, so there’s little in it that seems particularly new, except thinking of such ideas as threshold concepts. There was one thing that surprised me, though: the recognition of various forms of privilege.

Students’ confidence radically mismatches librarians’ assessment of their skills, two reports from EasyBib conclude, particularly in website evaluation, paraphrasing and direct quotation. Also, students are using the open web less often they were two years ago, and dramatically more librarians are stressing the role of faculty in promoting information literacy. The first report, Trends in Information Literacy: A Comparative View, was published in May 2014; the second, Perspectives on Student Research Skills in K-12 and Academic Communities, came out the following October; taken together, the two reveal some thought-provoking data on information literacy across the country.

A new survey reveals a wide gap between provosts and business leaders when it comes to judging college students’ readiness for the workplace. What can academic librarians take away from the controversy?

In my last column, I discussed research on cognitive bias and the human mind, and speculated that what librarians call information literacy is a deeply unnatural state. The human mind hasn’t evolved to analyze carefully or think critically without a great deal of effort, and even then, the effort is often misplaced. That’s of course one reason we educate people, and higher education particularly values traits like intellectual curiosity and critical thought that often help us overcome our natural intellectual inclinations. But education is not necessarily a salvation.

Librarians tend to view information literacy in light of the ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards. Information literacy is a set of competencies, a set of things we should be able to do. However, one of the many problems with becoming information literate in any robust sense is that it’s completely unnatural. The entire enterprise goes against the way the human mind tends to gather and use information. Human beings are animals perhaps capable of information literacy, but apparently designed to work in other ways.

Peer to Peer columnist Barbara Fister reflects on the need to reinvigorate instruction in light of how we now collect resources. This essay is part of an exclusive LJ series, Reinventing Libraries, that looks at how the digital shift is impacting libraries’ mission.

In a series of exclusive essays, thinkers from the library world address how the digital shift is impacting libraries’ mission. Peer to Peer columnist Barbara Fister reflects on the need to reinvigorate instruction in light of how we now collect resources. University of Washington iSchool’s Joseph Janes, in turn, calls for libraries to strike a balance between protecting privacy and innovating to add value—with patrons’ permission.

articles

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing