Related

The Seattle Public Library (SPL) is continuing to recover from a ransomware attack on Saturday, May 25. At press time, all branches were open, in-person and virtual programs and events were still being hosted, books and other physical materials were available for checkout, and online services provided by third-party vendors including ProQuest, Hoopla, Kanopy, and others were available to patrons. However, access to SPL’s ebooks and e-audiobooks, public computers, in-building Wi-Fi, printing and copying services, pickup lockers, museum pass services, interlibrary loan services, and some other online resources remained unavailable.

The Toronto Public Library (TPL) is in the final stages of recovering from a ransomware attack on October 28, 2023 that shut down the library’s internal network, website, and public computers. Although TPL managed to keep all of its 100 branches open and host programs throughout the ordeal, patrons were unable to access their library accounts online or use the library’s computers for more than two months.

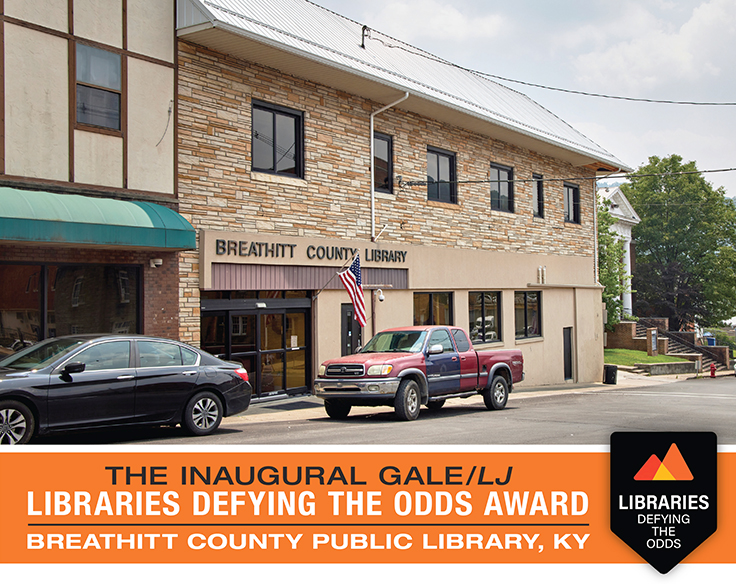

When a series of unanticipated hardships hit Breathitt County, KY, its library came forward to serve residents in large and small ways. For its critical community work now and looking ahead, Breathitt County Public Library is the recipient of LJ and Gale's inaugural Libraries Defying the Odds award. Charleston County Public Library, SC, is awarded honorable mention for its ongoing work to address food insecurity.

The Russo-Ukrainian War is more than a war between armies—it is a war between societies. Russia’s intention is not solely to defeat the Ukrainian military but to turn Ukraine into a gray zone by destroying it as a nation. Among the key casualties of the war are cultural heritage institutions, specifically those where ideas are preserved and exchanged: libraries.

In the violent rainstorms that hit central Appalachia this summer, one of the hardest hit institutions was Kentucky's Letcher County Public Library. Three of its four locations and a bookmobile were severely damaged. Cleanup has been steady but slow, but a GoFundMe fundraiser set up by Kim Michele Richardson, author of The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, has raised more than $30,000 to help the library rebuild and restock.

In April 2015 I wrote the LJ article “We Are the Monuments Men” in response to the burning of the Mosul Public Library by ISIS. I asked, What can be done to protect libraries, cultural properties, and artifacts? Sadly, seven years later, the world is witnessing a new conflict, and I am again asking what can we do as librarians to protect, preserve, save information, special collections, cultural artifacts, and rare items in times of conflict?

U.S. Libraries from the southern states up through the east coast were affected by several severe storms in a row: Hurricane Ida, starting on August 29, Hurricane Henri about a week prior, and Tropical Storm Nicholas, which produced rain and flooding on and after September 14. As with other natural disasters, library staff are simultaneously grappling with damage to their own homes and workplaces and serving the needs of their affected communities.

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) is a $1.9 trillion stimulus package passed by Congress on March 10. It includes targeted funding for various sectors of the economy and government impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, ranging from agriculture to small businesses to education—and libraries. Here are the ins and outs of how new federal funds will reach public libraries and how they can be spent.

The Califa Group—a nonprofit membership consortium of public, academic, school, research, corporate, medical, law, and special libraries across California—was recently awarded an Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS) grant for the Libraries as Second Responders project, which will help train library staff to serve communities that have been, and continue to be, highly impacted by COVID-19. LJ caught up with Califa Assistant Director Veronda J. Pitchford to find out more about the project.

When the long-awaited COVID-19 vaccines began to roll out in mid-December 2020, their distribution was immediately complicated by a shortage of doses and widespread uncertainty about who would be given priority. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued suggested guidelines for phased allocation. When it was not yet clear who would be next, many library workers, leaders, and associations began advocating for public facing library workers to be vaccinated as soon as feasible.

In the messy middle of the pandemic, library leaders share how things have changed since March 2020, their takeways, and continuing challenges.

HVAC systems may be an important tool for reducing COVID risk in library buildings; the details make all the difference.

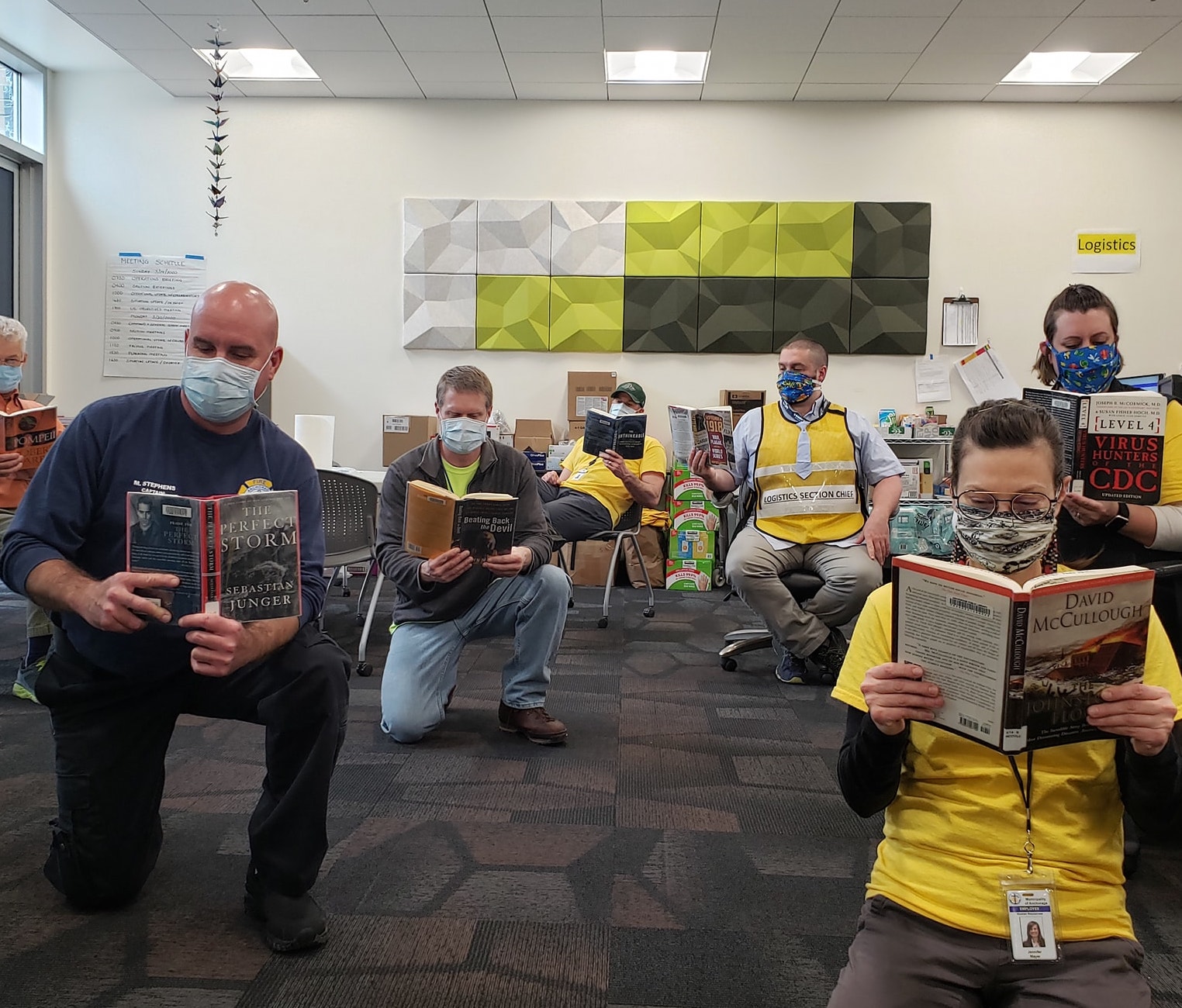

Librarians Elaine R. Hicks, Stacy Brody, and Sara Loree have been named LJ's 2021 Librarians of the Year for their work with the Librarian Reserve Corps, helping the World Health Organization manage the flood of COVID-19 information.

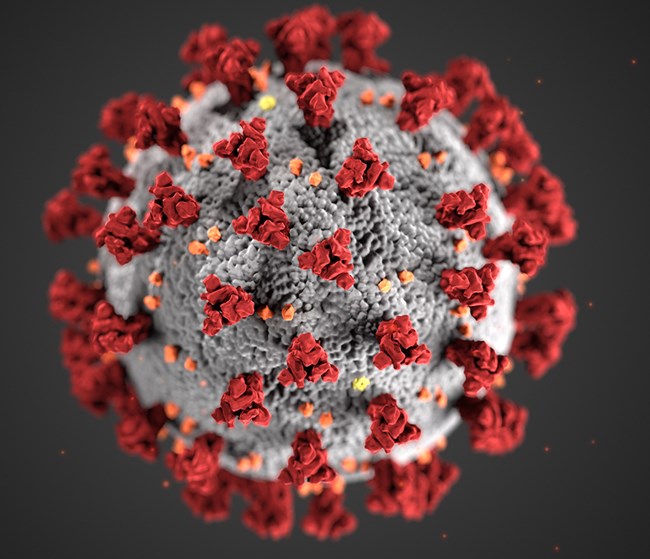

On November 7, Pfizer announced interim findings of a 90 percent effectiveness rate for its SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. On November 16, Moderna announced a similar interim finding of 94.5 percent effectiveness. While there are cautionary notes—these are the companies’ numbers, not the FDA’s, and at press time the trials were not yet complete—it is still a hopeful sign that the most stringent measures to contain community spread may be behind us by 2022. Yet the right-now coronavirus news is grim.

Despite precautionary measures against the coronavirus, such as regular testing and social distancing rules, as a second pandemic wave picks up across the country some schools are opting for an early shut-down of in-person learning. With classes pivoting to all online and residential students being sent home ahead of their Thanksgiving break—or being instructed not to return to campus afterward—academic libraries are once again adjusting to support their communities’ needs.

There are many ways that public libraries have helped during the West coast’s wildfire seasons: providing Wi-Fi and charging stations, helping residents file insurance and FEMA claims, offering parking lots as food and supply drop-offs, and even opening their doors as cooling centers. In a more dramatic turn, the University of California–Merced Libraries stepped up to safeguard the archives and records of the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in a last-minute evacuation.

UPDATE 9/10/20: On September 3, the REALM project published the results of the fourth round of Battelle’s laboratory testing for COVID-19 on five materials common to archives, libraries, and museums. Results show that after six days of quarantine the SARS-CoV-2 virus was still detected on all five materials tested. When compared to Test 1, which resulted in nondetectable virus after three days on an unstacked hardcover book, softcover book, plastic protective cover, and DVD case, the results of Test 4 highlight the effect of stacking and its ability to prolong the survivability of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

California’s 2020 wildfire season is one of the worst on record, with fires causing extensive damage to homes, businesses, and forestland. Libraries across the state have largely escaped severe fire or smoke damage. However, harsh smoke conditions have curtailed many libraries’ curbside or front-door pickup services, and the resources they have offered patrons in past wildfire seasons, such as assistance filing claims and in-library computer use, are impossible to provide safely because of COVID-19 related library closures.

No matter how conscientiously libraries stick to protocol, many have had to roll back reopening operations recently as employees fall ill or report positive COVID-19 tests or contact with others who test positive—or in some cases, as case counts in their areas rise or patrons refuse to comply with masking or social distancing regulations.

The COVID-19 pandemic abruptly shuttered academic libraries across the United States in March, leaving library staff scrambling to continue some semblance of library services. As states have taken steps toward reopening, academic institutions are now looking toward the fall semester and considering how they might safely open their own facilities.

In addition to enhanced cleaning protocols, training, and the public use of personal protective equipment like face coverings, the impacts of coronavirus are transforming how we design public spaces in the short and long term.

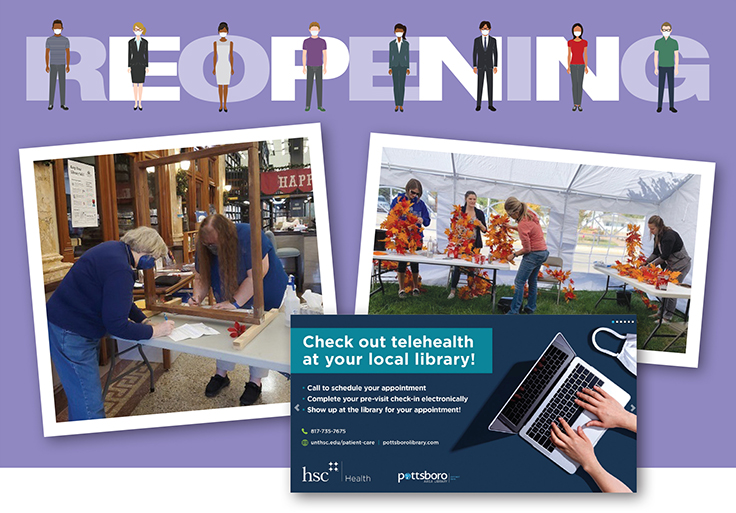

How do you reopen a library with no guidelines or best practices to work from? That’s the question public leaders and staff are considering as library buildings gradually open across the country.

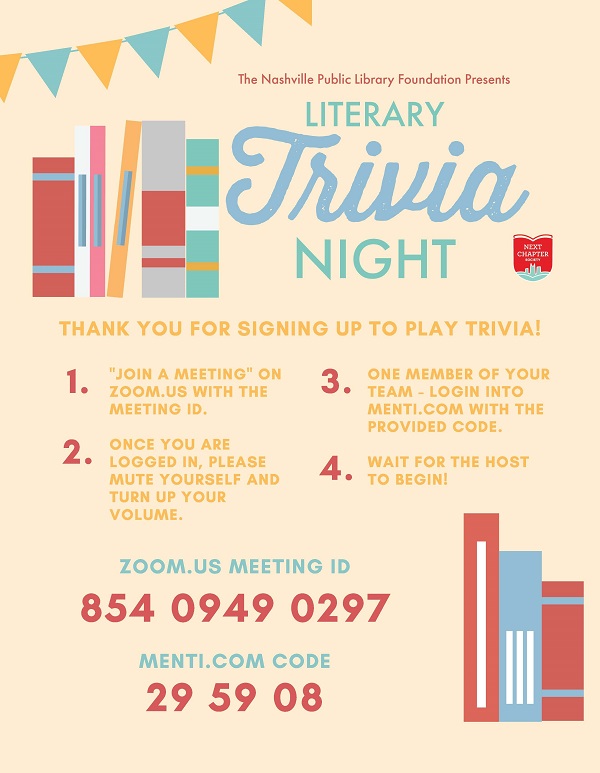

Many libraries are cancelling their galas and other in-person fundraising events due to the global pandemic. As a member of the Next Chapter Society (NCS), which works with Tennessee’s Nashville Public Library Foundation to fundraise for the Nashville Public Library (NPL), I worked with my committee to shift our summer activities online.

There is no 100 percent protection against the risk of COVID-19 aside from self-isolation, but we hope that the plans we’ve developed for re-opening our academic libraries will help you figure out how to provide the best protection for your staff and patrons.

Some libraries are already attempting to reopen their physical locations to the public, at least to some limited extent. Others, in harder hit areas or with local governments more focused on stopping the spread of Coronavirus, are still months away. But all are considering how to reconfigure their space, as well as their service, to best shield staff and patron health.

As we begin to reopen more and more libraries across the country the pressure you will feel as a leader is going to increase. You are crucial to your organization’s future right now. It’s okay to be nervous; it’s okay to be scared. Those emotions will not stop you from doing what you need to do. We can do this. You can do this.

As states and cities suspend coronavirus-related shutdown orders, two library apps—ConverSight LIBRO and CapiraMobile—are introducing curbside pickup features that will enable library staff to fulfill requests for books and other physical materials while maintaining social distancing recommendations and minimizing personal contact with patrons.

A handful of shuttered library buildings across the country are temporarily providing workspace that allows essential workers and services to properly social distance amid the COVID-19 crisis.

As a majority of academic libraries have transitioned to remote work in the wake of coronavirus-closed campuses, a growing number of United States–based archival workers—many of whom are in part-time, hourly, term-limited, or contract positions—are facing financial challenges. To help address some immediate needs, a team of archives workers partnered with the Society of American Archivists Foundation to create the Archival Workers Emergency Fund.

In 2016, a man set fire to a library in St. Cloud, MN. Allister Chang had an opportunity to speak with Karen Pundsack, director of the Great River Regional Library System, to reflect on what the library learned from the experience that is applicable to its COVID-19 response today. She demonstrates how library resilience transfers from one disaster to another, and in the process, the resilience of libraries as social infrastructure.

To maximize service—and to help safeguard the jobs of their colleagues from layoffs and furloughs—library and archives workers are crowdsourcing lists of work-from-home assignments. These lists continue to grow—as does the need for them.

The more people are coming into contact with one another, and the more people who are coming into contact with a surface (for example, a library book), the higher the risk becomes.

The Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) hosted a webinar on Monday, March 30, “Mitigating COVID-19 When Managing Paper-Based, Circulating, and Other Types of Collections.”

With most library buildings temporarily closed to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, some libraries are combining the need for meeting space with the shift to digital service delivery.

The coronavirus is shining a harsh light on the gaps in our social safety net, how essential libraries are as they try to fill more and more of those gaps, and the limitations of the library as an overstretched catchall solution to inequity.

As public, academic, school, and corporate library workers have been watching their workplaces close and striving to adjust to self-quarantining, medical librarians are facing additional challenges as a result of COVID-19.

With public libraries across Canada suddenly shuttered in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, library leaders and workers across the country are quickly adapting to still serve people, primarily online.

For library workers who are working to convince local governments to close the libraries and continue to pay staff during the COVID-19 pandemic, the best bet is to discuss the issue with their union. For those without a union, here are some advocacy ideas for convincing decision makers to close the library during the pandemic and support the staff.

On March 17, the American Library Association (ALA) released a statement recommending that libraries be closed to the public, after considerable outcry on social media at earlier statements that failed to take a position on the issue. Days before, Alison Macrina—librarian and founder of the Library Freedom Project—had begun work organizing the Library COVID-19 Solidarity Network, bringing together public and academic library staff to advocate for full library closure throughout the United States.

As recommendations to slow the spread of COVID-19 across the country become common knowledge, public events have been canceled, public schools have closed, and calls for social distancing to flatten the curve have become the norm. But some libraries remain divided on whether to remain open but suspend public programming, outreach, or meeting room rentals; limit hours; or close entirely.

When I started writing my editorial for the April issue last week, a mere handful of public libraries had closed to contain the spread of COVID-19, though many had canceled public programming. Less than a week later, nearly 500 have closed to the public. But there are more than 9,000 public library systems in the United States—and we should close all of them. Today, not in two weeks when the April issue lands on your desk.

In Seattle, WA, considered by many to be Ground Zero for the coronavirus in the United States, directors have have been modeling how libraries can deal with a public health crisis calmly and compassionately.

Civic unrest and natural disasters are not unique to the 21st century. But with the growth of rapid news cycles and citizen documentation through social media, careful documentation of these tragedies—in real time or close to it—is a responsibility that public and academic libraries, archives, and other cultural institutions are taking on more and more.

Few leaders ever anticipate dealing with a crisis of epic proportions. But as recent events in higher education demonstrate, leaders whose fortitude was formed in such a crucible bring a unique skill set to the position.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing