Related

While Texas continues to be a leading state in the number of book bans reported each year, a recent challenge at the Montgomery County Memorial Library has been reversed. The Texas Freedom to Read Project reported that a children’s book, Colonization and the Wampanoag Story by Linda Coombs (Aquinnah Wampanoag)—an account of American colonization and Native traditions described from an Indigenous perspective—was challenged in September and subsequently moved out of the juvenile nonfiction area to the fiction collection.

About 100 lawyers, library professionals, educators, students, and activists attended the Banned Books and Libraries Under Attack Conference at the Cleveland State University (CSU) College of Law, which featured more than a dozen speakers and panelists.

Between September 22 and 28, the nation’s library community once again “celebrates” Banned Books Week, an annual event established in 1982 by the American Library Association (ALA) to profile acts of censorship and book banning in schools and libraries across the nation. Beginning with a “Library Bill of Rights” that ALA adopted in 1939, library leaders worked hard during the 20th century to hone a national image as defenders of intellectual freedom, opponents of censorship, and proponents of the freedom to read. But between 1939 and 1982 that image evolved to become an information silo of librarianship’s own making, one that was silent on or indifferent to issues of race and libraries.

During Banned Books Week, this year September 22–28, LJ has seen a wide range of libraries celebrating the right to read in their communities: public, K–12, and academic; urban and rural; large and small—and, now, little. Little Free Libraries, the birdhouse-sized book exchange structures scattered across neighborhoods around the world, have joined forces with the American Library Association (ALA) and PEN America to encourage the distribution of banned books in the areas they’re needed most.

Two and a half years after launch, Books Unbanned has continued to grow as a vital resource for people in schools and communities where book challenges otherwise put content out of reach.

This Prison Banned Books Week, we’re calling for public library catalogs to be made available on prison tablets.

Voting on proposals for 2025 SXSW and 2025 SXSW EDU panels opened on August 6, and libraries are well represented among the many panels submitted for consideration.

On July 30, the U.S. Senate passed the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) 91–3. Supporters of the bill say that it will help protect children from the potential harms of social media platforms and other online services, but critics say that if the legislation passes the House and becomes law, it will lead to online censorship—potentially including politicized censorship by the Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general who would enforce the law.

In their shared hometown of Columbus, OH, at an event where readers celebrated their writing, Hanif Abdurraqib and Jacqueline Woodson sat with Library Journal for a conversation about libraries, book bans, and censorship.

As a book lover who works in the book industry, I have a job that aligns with my love for reading—and I get to work with librarians! Witnessing the sharp rise in attempts to ban books nationwide in recent years, I have become a vocal supporter of the First Amendment in ways that I didn’t expect when I began in publishing in 1988.

Frederick Douglass famously said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” This powerful and inspiring idea continues to resonate more than a century later, at a time when the essential services that libraries provide are more vital than ever.

Growing up in India as a young Sikh boy to aspiring middle-class parents, I understood their singular focus was to educate their children. Books were the windows that allowed me to gaze into a world far beyond my limited surroundings or imagination. The ancient tales of equality, courage, and righteousness from our scriptures, region, and history of valor ignited my imagination as I got older. At the same time, contemporary literature exposed me to the rich tapestry of cultures that coexisted in our vibrant nation.

Two and a half years ago, I was fired by the High Plains Library District (HPLD) in Weld County, CO, after I objected to cancelling programs for LGBTQIA+ teens and youth of color because they were “polarizing.”

Freedom to read issues are generating legislation—both library-adverse and library-protective—across the country.

When the LJ team decided to focus our June issue on censorship, I couldn’t get the idea of exploring the personal nature of book bans out of my head. Yes, the broad societal impacts of affronts to intellectual freedom are significant—but what do they look like and mean for individual readers?

At the 2024 Public Library Association (PLA) conference, held April 3–5 in Columbus, OH, presentations were notably targeted and useful. And, as a number bore out, those concerns overlap in many areas.

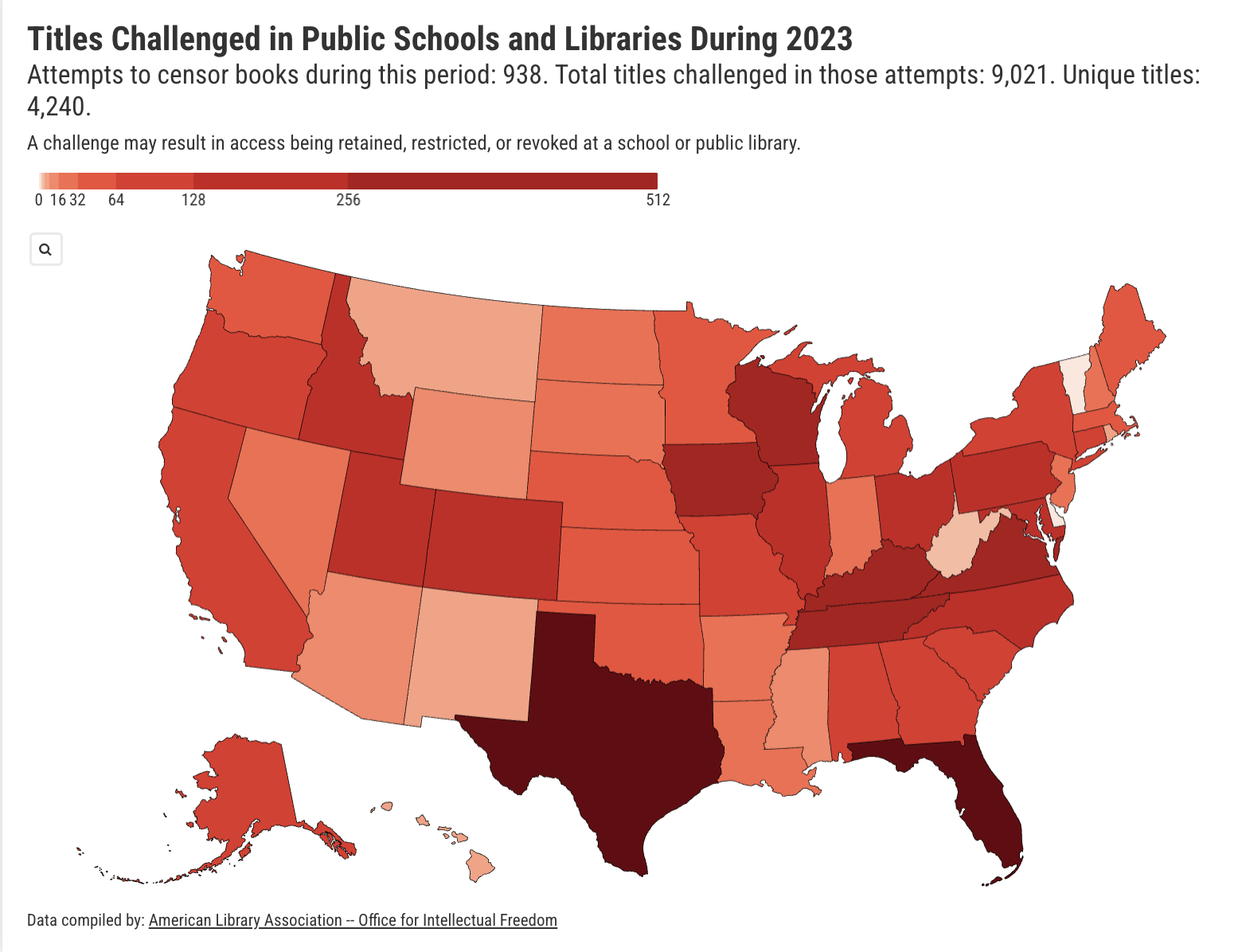

On March 14, the American Library Association (ALA) released its most recent book challenge data for 2023. According to ALA’s Office of Intellectual Freedom (OIF), which tracks challenges and acts of censorship in public schools and libraries across the United States, the number of targeted titles rose 65 percent from 2022—once again, the highest levels ever documented by ALA. In public libraries, numbers increased 92 percent over the previous year; school libraries saw an 11 percent increase. Challenged titles featuring the voices and lived experiences of LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC individuals made up 47 percent of those targeted in censorship attempts.

In the past two years of semi-occupation and warfare, public libraries in Ukraine have established themselves as actors in state defense. Among the first institutions to reopen after the war began, libraries continue to operate despite a shortage of funds and staff, and in the areas close to the front line, continuing shelling.

West Virginia legislators recently advanced a bill that would remove criminal liability protections for public library, museum, or school employees accused of displaying “obscene matter to a minor." Under House Bill 4654, which passed the West Virginia House of Delegates on February 16, in an 85–12 vote mostly along party lines, any adult who knowingly and intentionally displays obscene matter to a minor could be charged with a felony, fined up to $25,000, and face up to five years in prison if convicted.

Unite Against Book Bans—the national initiative launched by the American Library Association (ALA) in 2022 to help readers, libraries, publishers, and other institutions in the fight against censorship—this week launched a free collection of book résumés “to support librarians, educators, parents, students, and other community advocates in their efforts to keep frequently challenged books on shelves.” Separately, OverDrive subsidiary TeachingBooks last month announced the launch of a new Book Résumés Toolkit at ALA’s LibLearnX conference in Baltimore.

On January 30, in response to pressure from Gov. Kay Ivey, the Alabama Public Library Service—the agency that advises and administers funds to the state’s 220 public libraries—announced its official decision not to renew its membership with the American Library Association (ALA). But advocates are urged to look beyond the controversy over ALA to the larger issues in play, notably the growing influence that the state’s elected officials have on library freedoms.

When Patty Hector, former director of the Saline County Library in Benton, AR, was fired on October 9, it didn’t come as a surprise. A decision to shift control of the library from its board to county officials, driven primarily by Hector’s refusal to comply with a resolution to move certain books containing content about racism, LGBTQIA+ subjects, and sexual activity from areas where anyone under the age of 18 could access them, was proposed in April and passed in August. What may surprise some, however, is that Hector has thrown her hat in the ring for a spot on the Saline County Quorum Court, the same body that had her terminated.

A hearing held October 19 by the House Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education Subcommittee on graphic content in school libraries drew testimony from both witnesses concerned about the suppression of material and others troubled by the content they see in school libraries.

With the sharp uptick in challenges to books with LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC subjects and authors, this year’s Banned Books Week (October 1–7) resonates strongly with library staff and users alike. Public, academic, and school libraries from Los Angeles to Maine have launched local anticensorship campaigns—and some, like Brooklyn Public Library's Books Unbanned and New York Public Library's Books for All, are providing access to removed or restricted books nationally. One such initiative, the Digital Public Library of America’s (DPLA) Banned Book Club, has been providing challenged books to readers across the country, via the free Palace e-reader app, since its launch in July.

The ongoing debate over the freedom to read moved to the chambers of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, which held a hearing September 12 entitled “Book Bans: How Censorship Limits Liberty and Literature.”

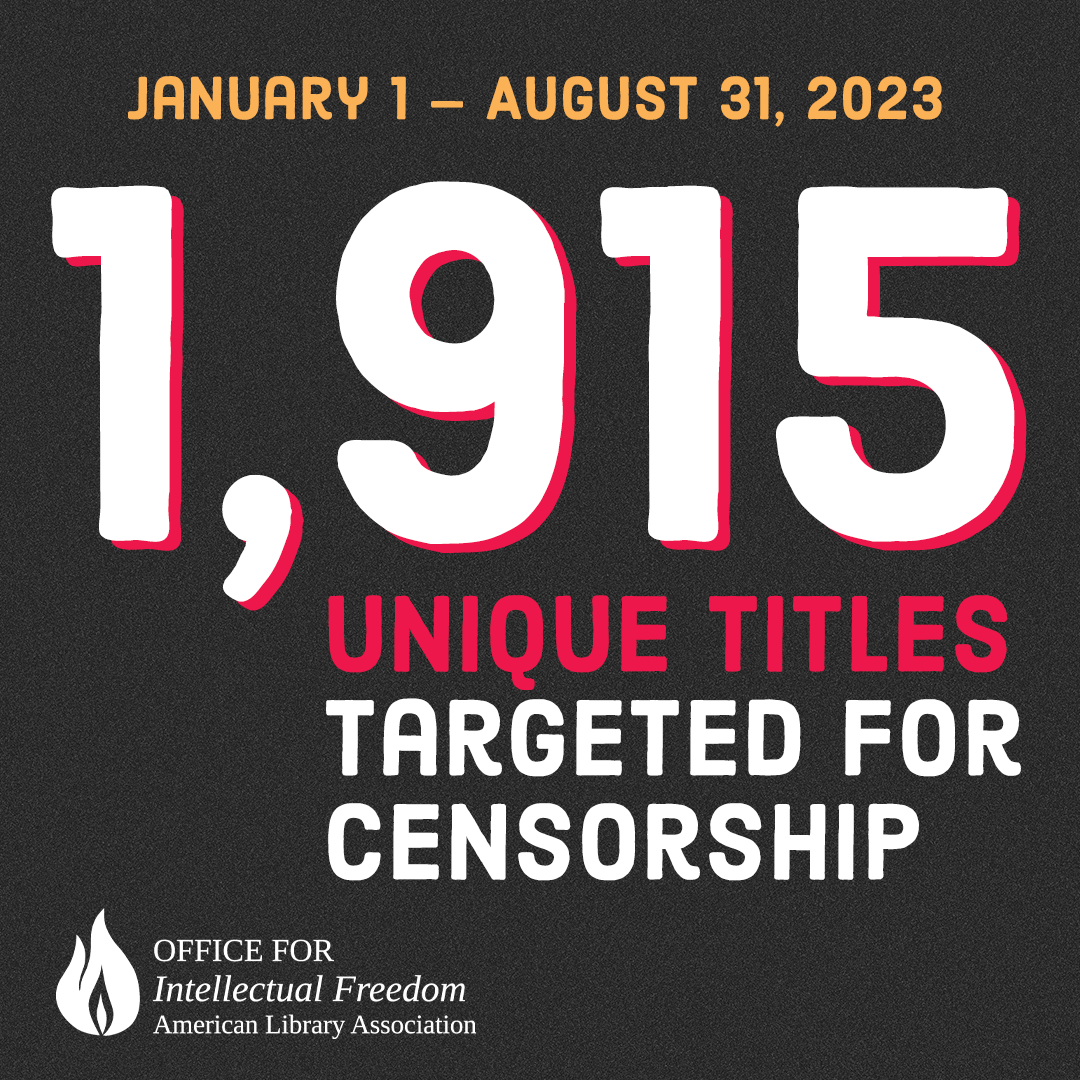

The American Library Association (ALA) has released its preliminary data on the attempted censorship and restriction of access to books and other materials in public, academic, and K–12 libraries during the first eight months of 2023. Between January 1 and August 31, ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom documented 695 challenges to library materials to 1,915 unique titles.

All eyes are on Texas as HB 900, the state’s controversial new book rating law, is slated to take effect September 1, 2023. Signed by Governor Greg Abbott on June 12, the legislation aims to prevent the sale of books deemed “sexually explicit” or “sexually relevant” to school districts by requiring book publishers and vendors to rate individual titles based on content.

Book banning groups are becoming more organized, but libraries are evolving new tactics to oppose censorship efforts, panelists said during the “#UniteAgainstBookBans: Advocate for your community’s right to read” panel with Emily Drabinski, Sara Gold, and Lisa Varga, with moderator Brian Potash, at OverDrive’s biennial Digipalooza conference in Cleveland August 9–11.

House Bill 1315, signed by the governor, regulates “pornographic media exposure” to K–12-aged children and “digital and online resources” provided by vendors to those children. The bill requires a vendor or provider of digital or online resources or databases to have safety policies and technology protection measures that prohibit and prevent a person from sending, receiving, viewing, or downloading content that officials consider “obscene.”

The overarching concern at ALA Annual in Chicago this summer was the proliferation of censorship attempts and book challenges at libraries of all kinds, in all states.

In the Southern California community of Huntington Beach, days before sharp budget cuts to the Huntington Beach Public Library (HBPL) were proposed—and then walked back—battle lines were drawn over a proposal to screen public library materials for what some deem sexually explicit or age-inappropriate content, and possibly limit access to those materials. The challenge, however, did not originate with an anonymous patron or member of a right-wing group, but with the city’s Mayor Pro Tem Gracey Van Der Mark.

On Thursday, June 22, the evening before the American Library Association (ALA) Annual Conference in Chicago officially began, Unite Against Book Bans hosted Rally for the Right to Read: Uniting for Libraries and Intellectual Freedom and an intellectual freedom award ceremony, attended by about 600 conferencegoers.

Library leaders, staff, and boards need to be prepared for increasingly sophisticated attacks on readers’ rights.

When a planned event came under attack, Downers Grove Public Library staff handled the hostilities, keeping safety a priority.

A bill that explicitly prohibits Illinois libraries from banning books is speeding its way toward passage by the General Assembly, and the Illinois Secretary of State said he wants “every librarian in the country to know we have their backs.”

Censorship efforts in the 2020s have moved beyond concerned parents to include restrictive legislation, library board power plays, and defunding.

The employees working the front desk are the ones who face the parent angry about a book’s content, the delegate of a group challenging the library’s right to select and shelve titles as it sees fit, or the media looking for an impromptu comment.

UPDATE: On March 31, a Federal District Court Judge in Texas handed down an injunction stopping the ongoing removal of books from the Llano County library system. The decision will immediately reinstate books that government officials have already removed from the system. The court found that library officials violated the First Amendment because they had targeted nationally acclaimed books based on their viewpoint and content. The Court’s order states: “The Court finds it substantially likely that the removals do not further any substantial government interest—much less any compelling one.”

Connecticut's Senate Bill 2, “An Act Concerning The Mental, Physical And Emotional Wellness of Children,” would, among many other things, allow every Connecticut municipality to designate a single sanctuary library—a place where patrons are promised access to books banned or challenged elsewhere.

Library directors often bear the brunt of intellectual freedom challenges from community members—even from their own boards—and some have chosen to leave.

According to Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry’s website, the intent of his online form for reporting graphic sexual content in libraries, created in late November 2022, is to protect minors. But the form—which has been called a “tip line” by the news media—has fueled criticism that it promotes censorship, targets the LGBTQIA+ community, and could escalate threats against library workers.

Brooklyn Public Library's Nick Higgins, Amy Mikel, Karen Keys, Jackson Gomes, and Leigh Hurwitz have been named LJ's 2023 Librarians of the Year for their work on Books Unbanned, providing free ebook access to teens and young adults nationwide to help defy rising book challenges across the country.

The EveryLibrary Institute, the companion organization of library advocacy group EveryLibrary, commissioned Embold Research, a nonpartisan research firm, to poll 1,223 U.S. voters on book banning. The survey found that nearly all (92 percent) have heard at least something about such censorship, and at least 75 percent will consider the issue of book banning when voting this November.

The American Library Association's Office of Intellectual Freedom tracked 729 attempts to ban or restrict library resources in K–12, higher ed, and public libraries in all of 2021, targeting 1,597 unique titles—itself the highest number of attempted book bans since ALA began keeping track of challenged books more than 20 years ago.

As book banning and censorship continues to ramp up across the country, particularly of work aimed at teens and young adults, New York City public libraries are stepping up to help young readers connect with challenged books.

The press freedom nongovernmental organization Reporters Without Borders (RSF, after its French title, Reporters Sans Frontières) has created a way for readers everywhere to access and read documents that have been banned or censored in the countries where they were published—through The Uncensored Library, a collection of articles and books housed in the virtual world of Minecraft.

Book challenges are not new. But what has changed, according to several people interviewed for this article, is the scope and tactics of the challenges.

The literary website Book Riot has teamed up with library political action committee (PAC) EveryLibrary in the battle against censorship in libraries. Through December 22, Book Riot will match donations to EveryLibrary up to $5,000 to help the organization combat the book challenges and proposed censorship measures that have ramped up across the United States this year.

Book challenges are, of course, nothing new to libraries. But they are ramping up in both frequency and intensity, and will take teamwork to resist.

A vote by the Lafayette Public Library, LA, Board of Control to reject a grant for a discussion on voting rights, which resulted in former director Teresa Elberson abruptly opting to retire, has highlighted longstanding issues between the board and library administration, and fears for the library’s future.

A bill filed this week in Missouri would give a specially appointed parental board oversight over public library materials deemed inappropriate for minors and proposes legal ramifications for librarians who don’t comply—leaving library leadership, workers, and supporters up in arms.

UPDATE: A similar bill in Tennessee, the Parental Oversight of Public Libraries Act (H.B. 2721), was killed in the House Cities and Counties subcommittee on March 11. The Senate companion bill, S.B. 2896, is expected to die as well.

U.S. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) on February 12 introduced the Data Protection Act of 2020, new legislation that would create the Data Protection Agency, an independent federal agency that “would serve as a ‘referee’ to define, arbitrate, and enforce rules to defend the protection of [U.S. citizens’] personal data.”

OIF Examines Legal Issues for Library Social Media and First Amendment “Audits” | ALA Midwinter 2020

At an early Saturday session at the American Library Association (ALA) 2020 Midwinter meeting, ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom (OIF) weighed in on several areas where libraries and their leaders and staff may have questions regarding their rights, offering resources for both public and academic libraries.

In response to a January 17 Washington Post article by reporter Joe Heim, the Washington, DC–based National Archives and Record Administration (NARA) has restored an altered promotional photograph in its lobby to its original state and published an apology on its website .

On October 29, writer Meghan Murphy spoke at a rented theater space in Canada’s Toronto Public Library (TPL) Palmerston branch. The discussion—“Gender Identity: What Does It Mean for Society, the Law and Women?"—was booked by an outside group, Radical Feminists Unite, and was not part of library programming. The appearance sparked protests against the library’s decision to rent the space to Murphy, particularly from the transgender and broader LGBTQ communities, as well as a barrage of criticism on social media.

Politics spurred a library budget and spending decision in Citrus County, FL, in October, when the Citrus County Commission withdrew a motion for the Citrus County Library’s request to purchase a digital New York Times subscription. While library acquisitions are often scrutinized from a budget perspective, this refusal raised attention when county commissioners went on record with non-financial reasons for voting against the electronic subscription.

The Leander Public Library (LPL), TX, has drawn criticism for proposed changes to meeting room and speaker policies—instituted not by the library, but by city government of this suburb north of Austin. LPL has been run by private library administrators Library Systems and Services since it was established as a city department in 2005. In the wake of several recent instances of programming deemed “controversial” by city leadership, amendments to library policy have drawn the attention of residents, city council members, and library and civil rights associations.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing