Related

One painful part of living through the pandemic for me was the sense that Americans were failing one another. Recent catastrophic weather events have brought back that same sense of unease. When deadly Hurricanes Helene and Milton made landfall last month, conspiracy theorists suggested they were manufactured for political benefit. Federal relief efforts were stymied by online misinformation, and a man was arrested for threatening FEMA workers. America, we’re not okay.

Whatever our personal politics across library land, the truth is that we live in a nation where a majority of voting Americans chose the candidate whose positions run counter to many policies and values that libraries support. So, what are we going to do about it?

As Lorcan Dempsey, formerly with OCLC, observed in portal: Libraries and the Academy (2008), “discovery happens elsewhere”—that is, people are using internet search engines, recommendations from social media, or emails from friends and colleagues to discover content. Search can be a powerful tool, provided you know what you are looking for. Yet there are significant problems associated with the search process.

My journey into librarianship was a bit unusual: Unlike those who began as a page or in an LIS role fresh out of grad school, my library career started in marketing. It was my job to understand the many ways the library brought value to the community and to develop stories and campaigns that shed light on the best aspects of our work. I was so inspired by what I saw in our branches that I eventually pursued a library degree. And as I deepened my knowledge, I saw that libraries could benefit from more attention to external communication.

Between September 22 and 28, the nation’s library community once again “celebrates” Banned Books Week, an annual event established in 1982 by the American Library Association (ALA) to profile acts of censorship and book banning in schools and libraries across the nation. Beginning with a “Library Bill of Rights” that ALA adopted in 1939, library leaders worked hard during the 20th century to hone a national image as defenders of intellectual freedom, opponents of censorship, and proponents of the freedom to read. But between 1939 and 1982 that image evolved to become an information silo of librarianship’s own making, one that was silent on or indifferent to issues of race and libraries.

For the past four years, EveryLibrary has been working to fight the book-banning movement. A large part of that fight is developing effective messaging against book bans, as well as conducting extensive message testing, surveys, and focus groups to understand the impact of messaging and determine which messages perform best.

Perhaps one of the truest versions of life in America’s small and rural communities can found each day in their public libraries, where residents connect.

Frankly, I should have seen it coming, but personal growth and change can be so subtle that you sometimes don’t realize you’re doing it until you’ve done it. When I literally squealed with delight upon discovering “Gardening with Monty Don” on the Hoopla BingePass at PLA 2024, it dawned on me that I was no longer someone who just liked plants...I’d become a gardener.

When the LJ team decided to focus our June issue on censorship, I couldn’t get the idea of exploring the personal nature of book bans out of my head. Yes, the broad societal impacts of affronts to intellectual freedom are significant—but what do they look like and mean for individual readers?

As a book lover who works in the book industry, I have a job that aligns with my love for reading—and I get to work with librarians! Witnessing the sharp rise in attempts to ban books nationwide in recent years, I have become a vocal supporter of the First Amendment in ways that I didn’t expect when I began in publishing in 1988.

Frederick Douglass famously said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” This powerful and inspiring idea continues to resonate more than a century later, at a time when the essential services that libraries provide are more vital than ever.

Growing up in India as a young Sikh boy to aspiring middle-class parents, I understood their singular focus was to educate their children. Books were the windows that allowed me to gaze into a world far beyond my limited surroundings or imagination. The ancient tales of equality, courage, and righteousness from our scriptures, region, and history of valor ignited my imagination as I got older. At the same time, contemporary literature exposed me to the rich tapestry of cultures that coexisted in our vibrant nation.

Two and a half years ago, I was fired by the High Plains Library District (HPLD) in Weld County, CO, after I objected to cancelling programs for LGBTQIA+ teens and youth of color because they were “polarizing.”

My mentor used to say that we really only need to ask two questions when recruiting people: “Do you like to solve problems?” and “Do you like to help people?” If so, you would like working in the library! I tend to think that she’s right—and if the Library Journal 2024 Movers & Shakers are any indication, the opportunity to support community, exercise creativity, and advance learning are forces driving their work.

It’s April, which means that in addition to celebrating spring’s arrival, I’ll be joining libraries across the nation in celebrating National Library Week.

In the past two years of semi-occupation and warfare, public libraries in Ukraine have established themselves as actors in state defense. Among the first institutions to reopen after the war began, libraries continue to operate despite a shortage of funds and staff, and in the areas close to the front line, continuing shelling.

As the 2024 election year heats up, positive framing will be increasingly important for libraries. I’m certainly guilty of falling into a “doom loop” of negativity when I think about what the future might hold for libraries—or even democracy itself. But we cannot be our smartest, most strategic selves if we focus only on negating anti-library rhetoric. We need to advance a positive pro-library narrative—one that is grounded in the history of our good work—to unite us as advocates and connect with voters across the spectrum.

I’ve been worried about library visits for a while now, but my concerns have largely focused on the effect fewer visits will have on the future of libraries. What I learned is that I had it backwards. Yes, there’s a danger to libraries when fewer people use them; but the bigger threat in decreased library use is to the community itself.

After a year spent enduring book challenges and politically charged barbs, no one can blame the profession for entering 2024 shell-shocked and exhausted. Yet, in the face of this trauma, we still find librarians and library workers who are resolute in their commitment to library values. Tired, yes, but smart about the ways in which they can provide important library service within the political context of their unique community and situation.

If you're seeing this, chances are you’re someone who identifies as a reader. And, as a reader, you may be shocked to discover that there are many American adults who just aren’t.

We already recognize the profound impact of pandemic learning loss: student performance in math and reading has hit its lowest levels in decades. What’s more, students demonstrated slower than average growth in the last school year, meaning learning gaps aren’t closing—in some cases, they’re growing. That’s where libraries can step in.

At a time when collaboration is endangered by conflict and critical thinking is often jettisoned in favor of the latest “hot take,” I can’t help but feel like library professionals are the leaders we need to secure a brighter future.

Most libraries don’t own their own ebooks. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to LJ readers, yet it’s a statement that continues to confound elected officials and administrators who get an astounding amount of say in how much money public and academic libraries are allotted. This is one of the reasons I, along with my coauthors Sarah Lamdan, Michael Weinberg, and Jason Schultz at the Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy at New York University Law, published our recent report, The Anti-Ownership Ebook Economy: How Publishers and Platforms Have Reshaped the Way We Read in the Digital Age.

The overarching concern at ALA Annual in Chicago this summer was the proliferation of censorship attempts and book challenges at libraries of all kinds, in all states.

At LJ, we watch the places where the law touches libraries. In recent years those areas of overlap have become unmistakable, as elected officials across the country propose—and pass—bills that would cut funding, prosecute staff, and remove collection oversight by libraries. We’re also looking for good news, though, and some emerging safeguards are promising.

This month, as we have every year since 2002, LJ celebrates a new cohort of Movers & Shakers. The 49 individuals profiled hail from every corner of libraryland and beyond. And while I agree that the award can’t compare with the sheer number of bright lights in the library firmament, I also think the emphasis on individuals isn’t a bad thing. Yes, these services need everyone on board, every day, to carry them forward and turn them into reality. But someone jump-started those realities, and that’s what Movers & Shakers celebrates.

Public and academic libraries should be leaders in moving away from fossil fuels, prioritizing investments in net-zero energy construction, renewable energy, and electric vehicles. This requires commitment from leadership in facility and budget planning. Library administration and governing boards of trustees need to step up to prioritize greenhouse gas emission reduction in their strategic and operational planning.

The employees working the front desk are the ones who face the parent angry about a book’s content, the delegate of a group challenging the library’s right to select and shelve titles as it sees fit, or the media looking for an impromptu comment.

This will be my last editorial for LJ. For me, this news is bittersweet; I’m excited to begin a new role elsewhere in libraryland, as managing editor of CQ Researcher at SAGE Publishing. But I will miss my colleagues, the opportunities I have had here to learn from and collaborate with librarians across the country, and my chance to bend your ear every month.

Library advocates have become increasingly sophisticated about collecting the emotional outcome stories that bring to life how libraries change lives. We may, sadly, need to start applying that savvy to collecting the outcomes of what happens when libraries are lost or gutted, whether due to pervasive underfunding, as in the UK, or ideologically driven campaigns against books, displays, and programs that represent LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC experiences, as is being attempted in the U.S.

At LJ’s recent Design Institute in Missoula, MT, the term places of refuge came up several times. It was new to me, but the meaning was clear from the context: individual-scale spots within the larger, communal library. But the refuge the library can offer is inherently temporary. For libraries to help make their whole communities places of refuge, libraries need to facilitate long-term planning for resilience to disasters that are more frequent and severe—plus, support government policy changes to slow and perhaps reverse that progression.

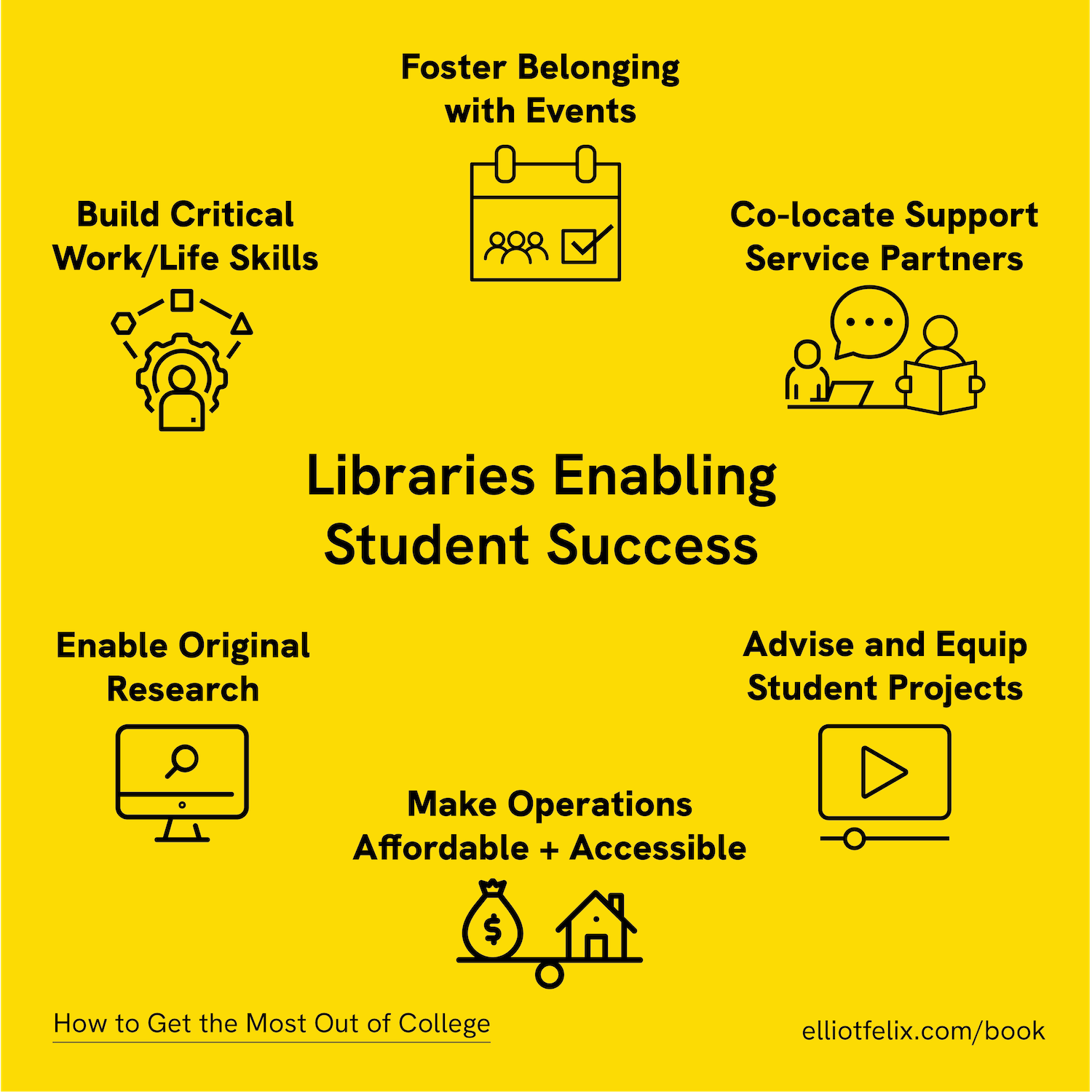

At a time when the cost of higher education is rising and so are questions about its value, libraries can lead the way in enabling student success and helping students get the most out of college. To do this, college and university libraries must continue their transformation from places to access information to places to also create, connect, and grow.

Teachers, librarians, and nurses have some important things in common. They do essential, mission-driven work. They’re mostly women (from 74 percent of teachers to 90 percent of nurses). They’re often underpaid. They’ve faced increased job stressors in the last few years. Many are thinking of leaving their jobs, if not fields—up to 77 percent of Texas teachers in a recent poll. The resulting shortages put more pressure on those who stay.

Recently I became acquainted with the creative works of a colleague, Jessy Randall, and I am impressed by the reciprocity between her archival work as the Curator of Special Collections at Colorado College and her poetry. Her latest book, Mathematics for Ladies: Poems on Women in Science, published by Goldsmiths Press and distributed by MIT Press, is a union of research and creativity.

A recent study shows truth in the saying, “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know.” Published in Nature, it examined Facebook relationships of 72 million people—84 percent of U.S. adults 25 to 44—and found that the biggest determining factor of a neighborhood’s less wealthy children obtaining positive economic mobility as adults was how much they connected with people outside their economic strata.

In February, after being alerted to the issue by a group of Massachusetts librarians, Library Freedom Project and Library Futures released a joint statement demanding accountability from Midwest Tape President and Hoopla founder Jeff Jankowski about hateful content and disinformation regarding COVID-19, the Holocaust, LGBTQIA+ people, and other topics on his company’s massively popular electronic content platform for public libraries. Six months later, there is still a great deal of disinformation to be found in Hoopla’s collection on topics ranging from LGBTQIA+ experiences to reproductive health to vaccines.

It is crucial that libraries help their communities grapple with pressing current issues. But it’s also important to rest, both individually and collectively.

Libraries cannot second-guess patron motives or impose barriers based on subject matter. I suggest that the best response is to turn the letter of the law back on attempted saboteurs.

On Earth Day 2022, Suffolk County, NY, Executive Steven Bellone announced a $12 million investment in electric vehicle charging stations. He chose the Lindenhurst Memorial Library—the second library in the country to be certified under the Sustainable Libraries Initiative’s Sustainable Library Certification Program—as the location for the press conference.

Responses to the pandemic from rural librarians represent an opportunity to better understand how libraries that want to make social well-being impacts can do so. The recent Institute of Museum and Library Services’ “Empowering Readers, Empowering Citizens” convening highlighted a host of pressing challenges facing libraries in this late-pandemic period—and the variation in the responses from urban and rural libraries couldn’t have been starker.

Like many people around the world, I have become enamored with Ted Lasso. This comedy from Apple stars Jason Sudeikis as the titular character in a show with storylines that are funny, sweet, sad, and, at their heart, kind.

In the midst of the myriad problems facing libraries in the United States—from the pandemic to burnout to the drastic increase in materials challenges—I want to celebrate a big win: the shift to libraries as at-scale providers of home connectivity for the digitally disenfranchised in their communities.

Who is in charge of your library? In Kentucky, in 2023, the answer will change. Gov. Andy Beshear’s veto of a state Senate bill was unexpectedly overridden in mid-April, enabling local politicians to take control of public library board appointments, and thus spending, and even the continued existence of facilities.

In 2021, the Annenberg School’s Library Archives accessioned the collection of Amy Siskind’s Weekly List website; however, the path to get there was complicated, and the final gift looked quite different from how it was conceived in the initial conversation.

In April 2015 I wrote the LJ article “We Are the Monuments Men” in response to the burning of the Mosul Public Library by ISIS. I asked, What can be done to protect libraries, cultural properties, and artifacts? Sadly, seven years later, the world is witnessing a new conflict, and I am again asking what can we do as librarians to protect, preserve, save information, special collections, cultural artifacts, and rare items in times of conflict?

The field needs to support innovation to meet our changing communities’ needs—but focus on invention can lead to taking essential duties, and the people who do them, for granted.

There is no more time to waste. Climate action is needed NOW. Libraries should be visible leaders and partner in this effort not only to protect the assets the public has entrusted them with but also to ensure library workers and community members have the support they need, through libraries, in the face of disruption.

Book challenges are, of course, nothing new to libraries. But they are ramping up in both frequency and intensity, and will take teamwork to resist.

The movement in public libraries toward eliminating late fines for borrowed materials is equitable—and practical.

Virtually every public library has something in its local history or current circumstances that could serve as the seed of a program that personalizes big-picture issues by focusing on their relevance to patrons’ own lives and communities.

It remains to be seen whether governments that relaxed or eliminated their mask mandates will move as quickly and decisively to put them back in place. But libraries shouldn’t wait for them to do so.

LJ ’s first readers’ advisory (RA) survey in eight years found that RA is a growing practice, but librarians want more training and tools to do it better, particularly in genres they don’t read for pleasure. Can crowdsourcing help RA keep up?

The 2021 ParkScore rankings, conducted annually by the Trust for Public Land, show a significant shakeup. It’s not because of major changes to the parks in the past year, but to the scoring: this year the Trust added equity to its decision matrix, which includes access, investment, amenities, and acreage. The resulting change in the lineup of top-scoring park systems shows how inadequate measuring overall access is for learning whether everyone is well served.

I never imagined that we would find ourselves honoring a second class of Movers & Shakers at a distance owing to the pandemic—albeit now with an end, perhaps, in sight.

I’ve been delighted to watch the ambitious program in Ohio in which 137 of the state’s 251 library systems (and counting) have chosen to help distribute about 2 million at-home coronavirus testing kits. At press time, libraries had already distributed nearly 60,000 tests through about 365 locations.

The challenge for libraries is, first, to obtain and spend federal funding, and second, to parlay that temporary help into a permanent paradigm shift. The new equipment will outlast the emergency. It is up to library leaders to document its ongoing impacts, so that when breakage and age take their inevitable toll, funders will find it unthinkable not to replace and upgrade the gear.

Much emphasis on STEM in libraries has focused on preparing patrons for careers in related fields, whether they are kids and teens or adults looking to retrain. But providing everyone with the tools necessary to grapple with the impact of STEM on their medical decisions, votes, and consumer choices, even if they never work in scientific fields, is just as crucial.

Congratulations on your inauguration. I know you face urgent challenges and must take decisive action at scale. I write to urge you to keep libraries in mind as you design structural remedies to ameliorate the immediate crises and prevent the next.

When I look at the state of the nation, my first reaction is frustration with squandered opportunities for the federal government to address both pandemic spread and economic hardship. Both could have been considerably ameliorated with sustained, coordinated action from the top over the past 10 months.

Navigating any place of employment can be complex for transgender and nonbinary people, but having an informed and supportive supervisor can make things easier.

As we think through the lessons we have learned over the past four years, one thing is quite clear: the way “we’ve always done things” is not sustainable for the well-being of our communities. We need to seek out those patterns that are emerging to systemically change the policy landscape of our society, economy and the environment and respect that leadership may look different in the coming years.

On November 7, Pfizer announced interim findings of a 90 percent effectiveness rate for its SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. On November 16, Moderna announced a similar interim finding of 94.5 percent effectiveness. While there are cautionary notes—these are the companies’ numbers, not the FDA’s, and at press time the trials were not yet complete—it is still a hopeful sign that the most stringent measures to contain community spread may be behind us by 2022. Yet the right-now coronavirus news is grim.

There is a threadrunning through almost all major headlines in our country this year: racial injustice.

Because information is critical to an informed electorate, the government formed an institution to ensure affordable access and avoid censorship. As a result, a high literacy rate led to economic growth. I’m speaking, of course, of the Postal Service Act of 1792, decades before the first modern public library opened in Peterborough, NH.

Welcome to Trans + Script, a column dedicated to amplifying the voices of transgender, nonbinary (nb), and queer library people and highlighting topics related to their experience in libraries. We’re in big cities, small towns, rural communities, on military bases, in areas of wealth, and in areas of poverty. Why is that reality important enough to be the first topic in this column? Because even though there are a lot of us and we’re everywhere, representation still matters.

How can librarians determine when their implicit bias has guided them into viewing Black patron behavior as dangerous, and hence guided them to call 911, and when a situation is actually dangerous and requires a police response?

While exact demographics are hard to come by, the informal consensus seems to be that members of most public libraries’ board of trustees or directors are largely white, well-off, and older. Meanwhile, the communities they represent are often far more diverse.

When the university moved to virtual instruction in March, Cornell University Library's Virtual Reference Response Team focused on building capacity in the ways we already connected with our remote users. Leveraging our Ask a Librarian suite of email, chat, and in-depth research consultations options became our primary concern.

Black Lives Matter. Indigenous people should be honored and recognized. Xenophobia is not acceptable. This movement across our country is a call to action, and libraries are redefining what the scope of this work entails and how we need to take the appropriate action to create a safe space for everyone.

Linked Data is only as useful as the metadata on which it depends, and poor quality metadata ultimately causes the challenges many librarians hope to address with Linked Data.

Libraries can and should continue to apply creative problem-solving to mitigate the worst impacts of this pandemic on staff and users. There is a limit to what even the most nimble, inventive, and dedicated libraries—or even consortia or associations—can fix. But that doesn’t mean there is nothing we can do. We need to think bigger and to throw the collective power of our profession toward advocacy for large-scale solutions.

In many towns across the United States, seeing members of the police in the public library is common-place. Off-duty officers moonlight as library security guards. Library programs like “Coffee with a Cop” aim to help the police develop closer bonds of trust with the community. And police are often called to deal with behavioral issues or threats to patron or staff safety. But as the past weeks of protest after the police killing of George Floyd, among others, make plain, for a substantial portion of patrons and staff, the presence of the police is itself a threat.

The massive change in life circumstances over the weeks since my last column have been strange, terrible, and beautiful—often all at once.

We need a National Library Workers Organization. The COVID-19 crisis has brought home to American workers their individual vulnerability—and their collective power.

Online classes pose many challenges, from baseline access to computers and the internet to requiring proficiency with new technologies and platforms, as well as motivation issues.

As we begin to reopen more and more libraries across the country the pressure you will feel as a leader is going to increase. You are crucial to your organization’s future right now. It’s okay to be nervous; it’s okay to be scared. Those emotions will not stop you from doing what you need to do. We can do this. You can do this.

Some libraries are already attempting to reopen their physical locations to the public, at least to some limited extent. Others, in harder hit areas or with local governments more focused on stopping the spread of Coronavirus, are still months away. But all are considering how to reconfigure their space, as well as their service, to best shield staff and patron health.

At many of our institutions, student-parents—students with one or more dependent children—are a growing population. Research in higher education has long demonstrated that student-parents face a number of obstacles to completing degrees and participating in college experiences. Academic librarians, however, have done little work to study what student-parents uniquely need to succeed academically.

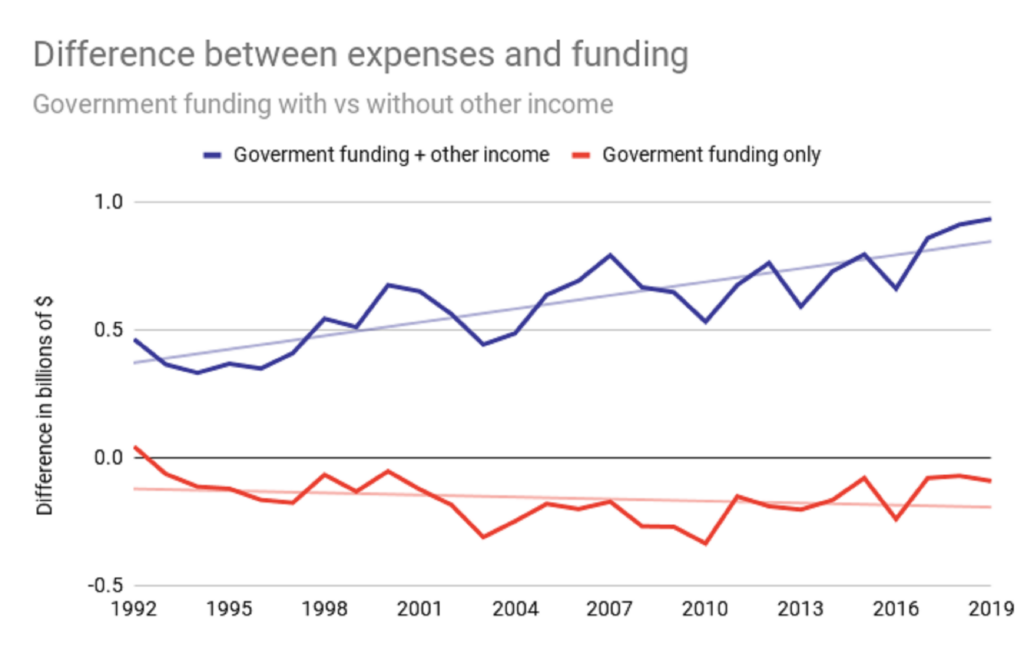

As public libraries do more and more in times of crisis to fill gaps in our social safety net, it is time to rethink how publishers and content providers relate and do business with public libraries and their customers. How can those relationships be retooled and reimagined to provide outcomes that are more beneficial for all?

There’s been a trend in articles coming out in major publications about how excited people are to get back to their libraries and how resilient libraries are. While they pay important attention to the needs libraries are still striving to meet in their communities, these narratives do nothing to expose the miserable realities that library workers are experiencing, or incite any kind of action to be taken in their defense.

It is important to take a moment, even in the midst of crisis, to honor this year’s Movers & Shakers. It is a waypost, a signifier of normalcy in a year from which so many landmarks are missing. But it’s also a reminder that we still need people moving us forward and shaking up our thinking—perhaps never more so than when we feel shaken by forces outside our control.

We all know that libraries are under attack, especially in regards to funding, pretty much all the time. I think part of our collective fear at this moment is local governments thinking that because we closed that we aren't really that important. I believe some are feeling that tension without verbalizing this sentiment. We worry about the short-term as well as the long-term consequences that our closings will have on our libraries. However, I do not thinking rushing to reopen solves this issue.

The more people are coming into contact with one another, and the more people who are coming into contact with a surface (for example, a library book), the higher the risk becomes.

The coronavirus is shining a harsh light on the gaps in our social safety net, how essential libraries are as they try to fill more and more of those gaps, and the limitations of the library as an overstretched catchall solution to inequity.

When I started writing my editorial for the April issue last week, a mere handful of public libraries had closed to contain the spread of COVID-19, though many had canceled public programming. Less than a week later, nearly 500 have closed to the public. But there are more than 9,000 public library systems in the United States—and we should close all of them. Today, not in two weeks when the April issue lands on your desk.

Taking a step back is about more than just creating an opportunity for others to step forward; it is about making sure that we are getting the most for our profession and communities.

Vocational awe. Burnout. Low morale. Precarity. Undercompensation. Together, the themes I see cropping up in LIS research, conference presentations, and Twitter point to a chronic problem.

Watching libraryland organizations in action over my eight years at LJ, I’ve been struck by the wisdom in structures that ensure the president-elect and immediate past president have roles in governance as well as the current leader. Getting insight into the decision process before you take over imparts invaluable training. Staying involved in a new capacity after your term is up creates continuity—and institutional memory can help prevent beginners’ mistakes.

Proponents of "grit" claim that developing a combination of passion and perseverance is the most significant factor shaping one’s life. The problem is, this contention ignores a great deal and has unintended negative consequences.

As the New Year dawns, I am thrilled to share the news that Meredith Schwartz, Library Journal’s Executive Editor, will be the new Editor-in-Chief, starting January 1. On the same day, I will take on the role of Group Publisher, overseeing the development of LJ, School Library Journal, and The Horn Book. In our respective new capacities, Schwartz and I will build on an effective partnership to bring you what you need to do your important work, through the many projects and initiatives that make up the Library Journal brand as a whole.

From the Bell Tower has explored the intersection between higher education and academic libraries for over a decade. It’s been a time of vast change, but what lies ahead is sure to hasten the pace of what will likely be more radical change. Paying attention to higher education will allow academic librarians to adapt to whatever comes their way.

As the year turns, so come the trends discussions and lists. There are certainly many that impact the people libraries serve, directly and indirectly. As I was starting to make my own list, Oxford announced its 2019 word of the year, “climate emergency,” defined as “a situation in which urgent action is required to reduce or halt climate change and avoid potentially irreversible environmental damage resulting from it.”

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing