Getting Out the Vote: Library Resources for Voter Empowerment

During voter education week, public and academic libraries step up efforts to ensure voters have what they need before they go to the polls.

The term “October surprise” was coined by then–presidential candidate Ronald Reagan’s campaign manager in 1980. Since then, depending on who’s got the goods up their sleeve, the last-minute reveal is both hoped for and dreaded by campaign machines. But this election season, and the years leading up to it, have been so tumultuous that we haven’t needed to wait for October. Libraries have kept up a daily battle, pushing back against book-banning groups and others who oppose full access to library resources, working against an onslaught of misinformation, combating voter suppression, and helping patrons to stay politically informed and active.

American Library Association (ALA) President Cindy Hohl tells LJ that “Much is at stake this election year—not only for libraries, but for our representative democracy.” With that in mind, Hohl points to ALA’s plans to highlight “learnings from librarians who have honed strategies to increase voter participation and sustain civic engagement.” In May, the association hosted a webinar that presented real-life examples of successful collaborations with local League of Women Voters (LWV), and the two organizations have collaborated on a 2024 Election Collaboration Toolkit.

With a contentious election upcoming, academic and public library workers, as well as organizations joining libraries, have been expanding their work to help democracy thrive in their communities and to address concerns around equity, access, and education at the polls.

GET PATRONS TALKING

|

ALA’s Reader. Voter. Ready messaging, in partnership with

|

One such issue is voter suppression. The Brennan Center for Social Justice at New York University notes that election misinformation “interferes with voters’ ability to understand and participate in political processes. And it has been weaponized by lawmakers to justify new voter suppression legislation.” At the ALA Annual conference held June 27–July 2 in San Diego, CA, ALA’s Social Responsibilities Round Table hosted the program “Combatting Voter Suppression in Your Library,” which introduced materials such as Rutgers University Libraries’ award-winning Voter Information Guides and American University Libraries’ absentee ballot toolkit—much voter suppression is centered on outlawing absentee voting.

The presentation covered three levels of democracy support performed by libraries, which fall along an increasing spectrum of engagement, notes Nancy Kranich, former ALA president and a speaker at the event. Libraries can inform patrons about voting, teach them to detect related misinformation, and host forums about democracy. Kranich advocates for the most engaged level, and described to session attendees how to organize a forum at their library.

This is an extension of the work she did as ALA president, Kranich explains, when she released Smart Voting Begins at Your Library, a guide that saw updated versions in 2020 and 2024. The presentation also built on work she did at Rutgers University, NJ, where she serves as teaching professor in the Master of Information program and coordinates the Library and Information Science concentration. In 2020, the Rutgers library held an online program in which it showed the film Rigged: The Voter Suppression Playbook, followed by an online panel discussion with the film’s creators, media specialists, voting rights experts, and others.

Kranich recommends that libraries coordinate “deliberative dialogues,” in which nonexperts sit with a trained guide and talk about an issue. Participants discuss a “wicked” or “unsolvable” problem and its causes, consequences, tradeoffs, and possible solutions and their pros and cons. National Issues Forums, which publishes its Guidelines for Facilitating Discussions, holds institutes that teach participants how to run these forums, and ALA offers training as well, with topics not limited to voting. “Working through the issues and weighing them in a neutral way can bring up surprising issues,” says Kranich, who observes that libraries are ideal hosts for these meetings because of the availability of meeting rooms where groups can sit in a circle to speak, and because the community tends to view the library as a nonpartisan location.

YOU PROMISED…

A pledge-based approach is another effective way for libraries and library-adjacent organizations to get out the vote. Patrons are not only reminded to vote, they are also asked to promise to do so and to take specific action in their communities. “Get Yourself Ready,” prompts ALA’s Advocacy and Public Policy site, “Reader. Voter. Ready.” There, patrons commit to “being informed, registered, and ready to vote this election year” by filling in a contact form that is both a pledge and a signup to receive election-related resources and engagement opportunities.

ALA urges two further steps: “Get Your Community Ready” and “Readers to the Polls.” The latter content is coming soon,

according to the site, but plenty of community resources are available under the former tab, including links to organizations such as Voters Unite Against Book Bans and resources such as ALA’s Media Literacy for Adults and the association’s Government Documents Round Table (GODORT) voting and election toolkits.

Also asking library users to take a pledge is EveryLibrary, a “staunchly nonpartisan and fiercely pro-library” organization that “helps public, school, and college libraries win funding at the ballot box [and supports] grassroots groups across the country defend and support their local library against book banning, illicit political interference, and threats of closure.” EveryLibrary has also started a petition for librarians and others to sign in protest of Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s plan whose opening section, explains EveryLibrary, is “filled with allegations of criminal conduct by librarians, publishers, authors, and educators and argues in favor of criminal charges and incarceration.”

EveryLibrary’s work “is inherently tied to politics,” says Sanobar Chagani, democracy projects coordinator at EveryLibrary, “because our goal is to protect access to information, which is an essential part of democracy, and that’s why we offer support to local organizers who are fighting against censorship and book bans in libraries across the country.” Ahead of the November elections, the Libraries2024 initiative—which includes the previously mentioned pledge—is a natural extension of that work, Chagani notes, because “it informs voters about the issues related to libraries that directly affect them, including access to public education, book bans and censorship, and their rights as taxpayers.”

EveryLibrary also runs an ongoing VoteLibraries campaign, which “encourages more libraries to get involved in the political process by encouraging them to serve as polling places and ballot dropoff locations and to host conversations about political misinformation and disinformation.” Asked how else libraries can continue the work after this year, Chagani suggests that they “constantly make conscious efforts to promote democracy and voter participation and fight against political violence and misinformation.” There are also inexpensive or free efforts libraries can undertake, she adds, including offering “books and materials related to voting, democracy, and the political process; creating local candidate and issue guides; and partnering with organizations that are already doing this work.”

FRIES WITH THAT?

Sacramento Public Library (SPL) already has its boots on the ground. Deputy Director of Public Services Cathy Crosthwaite tells LJ that ballot boxes are provided at every SPL location starting 30 days

|

Glenview Public Library, IL, spotlights information literacy librarians in its newsletter |

prior to the election, and every staff member who wants to (“99 percent of them do”) can help voting patrons, once the staffer has taken an oath to follow election procedures correctly. The library also reserves community rooms in 14 locations so that they can serve as vote centers starting on November 1. “In preparation,” says Crosthwaite, “we train our staff on what they can and can’t do. We don’t talk about politics. If people have questions, we guide them to where they can find accurate information.” The staff are also prohibited from wearing clothing with election-related messages. “So we say, ‘Wear your library shirt, wear your freedom to read shirt, wear buttons that say vote at the library,’” says Crosthwaite.

At the five busiest sites, the library sets up drive-through voting. “People LOVE it,” says Crosthwaite, and even arrive in their cars before voting opens. The ballot box is tied and locked to a table in the drive-through, and the service is only open when the library has voting staff available “so we can make sure [the votes are] really getting counted”—a concern that patrons often express. “We get our Friends group involved in staffing the drive-through,” notes Crosthwaite. “They have taken this on as a key contribution to the library. The drive-throughs wouldn’t happen without the Friends. Even when branches were closed, they brought the ballot boxes out every day during COVID.” The Friends also become involved when the library budget and other initiatives are on the ballot. Library staff “can’t promote [passage of the ballot] to voters, but we can educate them on how wonderful the library is, and leave promotion to the Friends,” explains Crosthwaite.

Every year with a big election, SPL works with Professor Kim Nalder at California State University–Sacramento to get more information to the city’s voters. Nalder and her team put together a program that goes through every ballot initiative. The library also invites legislative analysts to present ballot initiatives, and Nalder’s team offers corresponding information on who’s supporting and funding each initiative and other relevant facts. This is all presented in person at the library and as a video on the library’s voting website, says Crosthwaite, and the library presents a related fiction and nonfiction reading list alongside. “As a librarian,” she notes, “you find yourself involved in things you never thought you’d be a part of. But I saw a need, especially when they’re trying to take away the rights of people to vote. I dove in head first. I want to make sure that anyone eligible to vote can do so.”

READY TO RUN IN TOLEDO

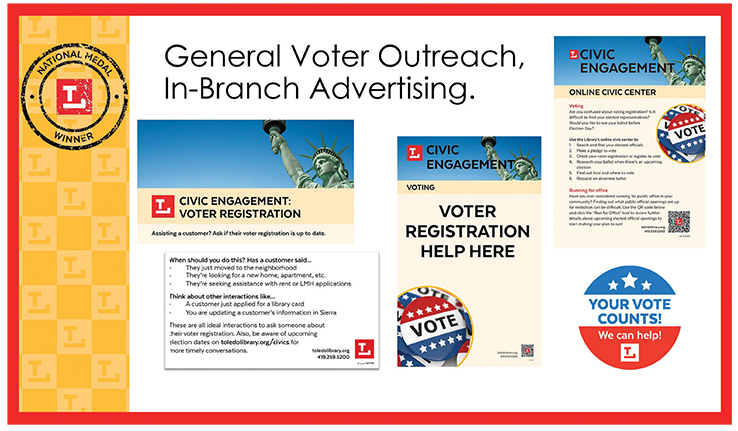

Toledo Lucas County Public Library (TLCPL), OH, does extensive voter outreach as well. The library launched a civic center in 2022 and now has a civic engagement page and online “Run for Office” tool that helps locals learn about open political positions in their area. Lucas Camuso-Stall, TLCPL’s director of government relations and advocacy, explains that the civic engagement page offers critical information about upcoming elections, including key dates, so that patrons know when an election is happening and when to register.

The online civic center, which is powered by information from Ballot Ready, asks users for their address to locate their polling place. They can read about their representatives “all the way from the local school board up to the President of the United States.” The user can also see if they’re registered to vote and request a ballot; when there’s an upcoming election, they can research the issues that will appear on their district’s ballot. “So when they show up to early voting or on Election Day, they feel comfortable,” says Camuso-Stall.

Patrons have shown great interest in the library’s Run for Office tool. “Folks really appreciate an extra resource for all this,” notes Camuso-Stall. “A lot of the information can be found elsewhere.... But here it’s in one place. It makes the civic engagement process easier, and we think that if we can do that, we should.” The library also hosts an event with the health department and others to help patrons get the ID they need to be able to vote, which can be “a pretty big hurdle,” says Camuso-Stall.

Gerrymandering is another issue facing voters in Ohio. Redistricting has resulted in some libraries shifting into new districts despite not relocating. When a library has been redistricted, TLCPL uses it as an engagement opportunity. The civic engagement staff invites the new legislators to the facility (they also do this for any newly elected officials, even if the district hasn’t changed). The library has also held “multipartisan, multi-viewpoint” panels to get patrons more informed about voting and running for office. The March “Her Voice, Her Run” event featured “speed networking” with women elected leaders. Community members could speak to a new civic leader every 20 minutes to find out how she ran, what is required of her role, and how she knew it was time to run for office. “Building strong democracies involves people feeling they can be more directly involved by running,” says Camuso-Stall.

“NOT ALL NEWS SOURCES ARE EQUAL”

At Glenview Public Library, IL, located in a suburb of Chicago, the problem of misinformation is a major focus. Linda Sawyer, manager of youth community engagement, explains that in 2023, the library’s executive director, Lindsey Dorfman, raised the problem to staff, and since then the library has delivered quarterly programs on misinformation-related themes. The library’s newsletter, “The Spark,” has introduced Glenview’s librarians in a spotlight article titled “Meet Your Information Literacy Experts.”

In a prior job, Sawyer worked with the News Literacy Project (NLP), a nonprofit organization that she describes as phenomenal. At her suggestion, Glenview now works with NLP, which aims to create “a national movement to ensure that all students are skilled in news literacy before high school graduation.” The library and NLP partnered on two projects: “Memes and Misinformation,” designed for middle- and high-schoolers and their parents; and an all-ages conversation/panel on misinformation. “[NLP’s] education is so vitally important,” says Sawyer, “it has been focused on schools, and we’re working with them to get public libraries more on their radar.”

The community conversation informed patrons “how to vet information as you’re engaging with media from political campaigns,” says Sawyer. The program reminded attendees that “not all news sources are created equal and included a lot about soundbites,” she adds. It also included a look at visual deception, showing attendees “doctored” photos of President Biden and former President Trump. Closer to the election, Glenview will offer a series in partnership with the LWV to help people better understand election issues and voting. “Libraries today are a community center,” notes Sawyer. “Our mission is to engage our community in the exchange of ideas and these programs are part of that.”

|

Getting the word out with Toledo Lucas County Public Library’s Civic Engagement page |

VOTE!

Stevens Institute of Technology, a private research university in Hoboken, NJ, serves many students from outside the state, Library Director Linda Beninghove tells LJ. It’s therefore necessary for the library’s democracy-boosting efforts to cover more than local resources. The library’s Head of Research Services Vicky Orlofsky does programming as part of her duties and works on voter outreach. In the runup to the 2016 presidential election, Orlofsky created a LibGuide called “Vote!” that focuses on New Jersey voting but also provides information for Stevens’s voters from other states. She supplements the guide with a low-tech but effective tool: a whiteboard that she updates daily with various kinds of information students need, including voting deadlines and resources. The voter education she performs is modeled on work done by Aimee Slater at Brandeis University, Orlofsky explains. (Brandeis also holds an “Absentee Jamboree,” she adds—a get-together at which out of state students can fill out their absentee ballots.)

“Civic engagement has been a personal interest of mine forever,” says Orlofsky. “While it is not something that is the primary objective of an academic library the way it would be for a public [library], I think it is something that is important for us as a library and as an institution to support.” As interest in voting wanes in non–presidential election years, Orlofsky takes the opportunity to remind students that state and local elections are also worth their attention. It has become a “low-key but known thing,” she says, that the library helps with resources such as voter registration forms, though these efforts complement work by other departments—the Office of Undergraduate Student Life, for example, undertakes National Voter Registration Day initiatives—and the library promotes those other departments’ work.

Beninghove notes that helping students figure out how and where to register and how to get information on candidates, issues, and voting is a form of information literacy. “This can be a very overwhelming, daunting process. Our work helps students understand that even after graduation, a library is a place where they can get reliable, helpful, and nonpartisan information,” she explains. Libraries that help new voters to register will find helpful information in Gale’s recent “Get Students Excited to Vote” blog post; the vendor’s information on increasing digital media literacy ahead of the election is useful as well.

EDUCATING THE WHOLE PERSON

Also using a LibGuide to get information out—one with an unusual “Follow the Money” section on campaign finance—is Sophia Neuhaus, social sciences and government information librarian at Santa Clara University Library, CA. “Santa Clara is a Jesuit school,” Neuhaus explains. “Jesuit education is about educating the whole person, and civic engagement is part of that.”

The library has hosted a variety of election-related events, Neuhaus says—in 2016, for example, 300 attendees showed up to watch the first debate between candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. The library has also hosted voter registration and election-night viewing. Neuhaus encourages other libraries to do the same. “[These events are] a great way to get students involved and politically aware,” she says.

Neuhaus’s LibGuide promotes civic engagement outside of voting season, offering polls on political issues—and participation is solid. A poll asking whether the New York state criminal case against Trump was politically motivated, for example, got 1,500 responses. Neuhaus notes, however, that the LibGuide’s links to interactive maps, powered by the website 270towin.com, get the most attention on the site. In April 2024, there were 3,400 views of the maps and 3,600 page views overall.

State library associations cross the public-academic divide, providing much-needed resources to constituent libraries. The Maine Library Association (MLA) is launching a partnership with the LWV of Maine that is closely modeled on the national partnership, MLA President Amy Wisehart says. “The League will provide educational resources tailored to libraries, trainings for library staff to help patrons register to vote online, and a nonpartisan election guide distributed to libraries,” she explains. The LWV will also connect with individual libraries where staff are interested in hosting candidate forums.

ALA President Hohl echoes all the library workers putting in the extra efforts to keep their communities aware and activated. “We want every reader who’s eligible to be registered to vote, informed, and ready to show up at the polls in November,” she says. Equally important, “we as library professionals have to commit to showing up at the polls. There are more than 370,000 library workers in about 120,000 libraries in this country: we can make a difference.”

Libraries nationwide have the job well in hand, and no doubt will start the work all over again on November 6, no matter the outcome of the 2024 election.

The librarians interviewed for LJ’s September 2024 feature on voter engagement have published a variety of LibGuides, toolkits, and resources. Check them out, as well as material from the American Library Association, EveryLibrary, and more, at Resources for Getting Out the Vote. Resources are listed in the order in which they appear in the article.

Henrietta Thornton, formerly LJ’s Reviews Editor, is Information Literacy Content and Strategy Manager at Infobase and a cofounder of free crime-fiction newsletter firstCLUE.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!