After the Audit | PLA 2022

Collection Diversity audits, while crucial, can present a daunting challenge. What can tip the balance toward deciding the work is worth it is a concrete plan for how the knowledge gained can be directly translated into action. At the “After the Collection Diversity Audit” session at PLA, a mixture of in-person and virtual panelists shared their experiences and strategies.

Collection Diversity audits, while crucial, can present a daunting challenge. What can tip the balance toward deciding the work is worth it is a concrete plan for how the knowledge gained can be directly translated into action. At the “After the Collection Diversity Audit” session at PLA, a mixture of in-person and virtual panelists—including Celia Mulder, head of collection management and system administration, Clinton-Macomb Public Library, MI; Sarah Voels, community engagement librarian, Cedar Rapids Public Library, IA; Anitra Gates, technical service manager, Erie County Public Library, PA; and Amberlee McGaughey, children's librarian, Erie County Public Library—shared their experiences and strategies.

Collection Diversity audits, while crucial, can present a daunting challenge. What can tip the balance toward deciding the work is worth it is a concrete plan for how the knowledge gained can be directly translated into action. At the “After the Collection Diversity Audit” session at PLA, a mixture of in-person and virtual panelists—including Celia Mulder, head of collection management and system administration, Clinton-Macomb Public Library, MI; Sarah Voels, community engagement librarian, Cedar Rapids Public Library, IA; Anitra Gates, technical service manager, Erie County Public Library, PA; and Amberlee McGaughey, children's librarian, Erie County Public Library—shared their experiences and strategies.

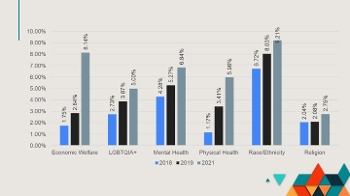

Some panelists audited every title in a physical collection, while others opted for a random sampling. Some considered a broad range of categories, including race, ethnicity, LGBTQIA+ identity, mental health, and religion, while others focused on a single aspect such as BIPOC characters. Even how to categorize characters requires judgement calls: In Erie County, the library used a category of “white or presumed white” to allow for main characters whose race was never identified explicitly.

One of the most interesting takeaways was that fears that books focused on marginalized protagonists would circulate less were unfounded. At one library, they circulated almost exactly in proportion to their percentage of the collection. Another panelist, however, cautioned that it might take time to build up to that level if past collection development practices have created a lack of trust among members of underrepresented groups in the community. The panelists cautioned against applying strict mechanical formulas—such as weeding all books that circulate less after two years—because you can end up with gaps in important categories that may serve numerically fewer people, but are very important to the people they do serve. Personal experiences they cited include weeding books on Hannukah and Kwanzaa because they circulate less than Christmas titles, or Coretta Scott King award–winning titles.

In addition to manual auditing, tools mentioned included Diverse Bookfinder, a picture-book–focused collection analysis tool hosted at Bates College; Follett School Solutions’ Titlewave Diversity Analysis, Ingram Inclusive, and a forthcoming service from Midwest Tape. (Those interested in such services might also look into analogous offerings from Baker and Taylor and, for e-collections, OverDrive.) While such tools are not a complete replacement for manual audits, more than one librarian on the panel reported that their manual counts were similar to those delivered by the software, which built trust in the results.

Multiple libraries reported that their teen fiction sections were the most diverse, while thrillers are particularly homogenously full of cis white male authors. In nonfiction, panelists recommended looking at publication dates, as older works are likely to be less representative and more stereotypical. Certain topics, such as Thanksgiving, need to be examined especially closely. One panelist suggested that, while you should keep books that are circulating, librarians should offer alternatives and, when they stop circulating, they should be weeded. While biography was easier to audit than most nonfiction, looking at the subject’s occupation found that while the overall percentages might look good, the collection featured Black subjects primarily as athletes, while most politicians were white.

Other learnings from the process included that purchasing was only part of the issue—librarians also needed to work on cataloging using more inclusive and up-to-date terminology, and including representative titles in displays and programs—for the latter, they suggested, track inclusion right along with attendance. They urged rebuying as you weed and using alternative review sources beyond professional journals. The panelists also urged building buy-in from staff with training on overcoming personal biases, preparing for blowback not only for leadership but also those with social media responsibilities, and examining the request for reconsideration policy to make sure it’s robust ahead of any challenges. When it comes to setting numerical goals, some are targeting their own community’s census percentages. Mulder set a 25 percent goal but finds in practice the team frequently exceeds it. One panelist said the hard goal was simply “be better,” while the soft goal is 50 percent, since the library cannot really know the demographic prevalence of mental health issues or other invisible marginalization in its community. The good news is that “being better” is very achievable and that measuring what we value works: One library found only 15 percent diverse books in its initial audit. After a year of focused collection development and a reaudit, that number rose to 25.5 percent, and a year later, to 35.5 percent.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy: