United We Stand: A Conversation with Hanif Abdurraqib & Jacqueline Woodson | Censorship

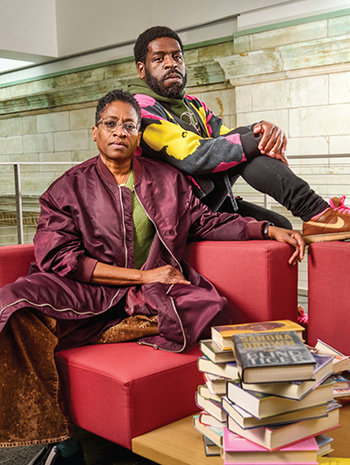

In their shared hometown of Columbus, OH, at an event where readers celebrated their writing, Hanif Abdurraqib and Jacqueline Woodson sat with Library Journal for a conversation about libraries, book bans, and censorship.

Two authors talk censorship, stories, and support for librarians at a hometown book festival

|

Photo by Tommy Feisel ©2024 |

Several program attendees approached the table where authors Hanif Abdurraqib and Jacqueline Woodson sat following a live taping of Page Count, a podcast produced by the Ohio Center for the Book, during the 2024 Ohioana Book Festival.

Several program attendees approached the table where authors Hanif Abdurraqib and Jacqueline Woodson sat following a live taping of Page Count, a podcast produced by the Ohio Center for the Book, during the 2024 Ohioana Book Festival.

Abdurraqib and Woodson were gracious with the fans, greeting them warmly and listening to their stories. A young couple told Abdurraqib they discussed one of his books on their first date. An older Black woman hung back while she waited for an opportunity to take Woodson’s hand and quietly whisper a message that brought a smile to the author’s face.

In their shared hometown of Columbus, OH, at an event where readers celebrated their writing, Abdurraqib and Woodson sat with Library Journal for a conversation about libraries, book bans, and censorship.

Let’s start with your experiences with libraries—what role did they play when you were young?

Abdurraqib: When I was a kid, I used to go to the Livingston branch of the Columbus library. After maybe two weeks of going there every day, librarians clocked what I was reading, and said, “Here’s something else that you might like.” They would do that without any questions about “Are you the right age to be reading that?” It was just kind of, “I see you as a curious person who is looking to expand your curiosity about the world, or maybe some understanding about yourself. And here’s a pathway for that.”

Woodson: When I was a kid, I loved picture books even though I was “too old” for picture books. And, at my Washington Irving branch, they were shelved very low for the little kids. My librarian knew that I would come after school, and she just put a chair and a desk there. And she’s like, “Jackie, your section is waiting. I know you love these, so here they are for you.”

Jacqueline, you’ve talked about the importance of reading stories that don’t necessarily have a happy ending as a gateway to empathy. In what ways do stories have that power?

Woodson: I think about the history of my reading, and how I learned to care through character. Meeting characters like the Little Match Girl, who basically starved and froze to death, in a children’s book, and how I went back to that book again and again because I wanted her ending to be different. It felt like I had some power over that. I began to understand that these things happen in the world—that people don’t have enough—and that there is something that we can do to work toward the end of that plight.

Just the idea that people don’t want kids to have that feeling, to have the emotion that leads them to understanding ways in which they can have an impact on a greater good—it’s bananas to me.

Hanif, you’ve described stories as “a way to keep loved ones alive and as a way to contextualize histories” and “a way to push back against things I was told to believe and accept.” In this moment, when so many books are being challenged or outright banned, what do we lose if those stories go away?

Abdurraqib: I think people, particularly people at the margins, in multiple margins of intersection, lose the potential to see themselves reflected back and to see their modes of survival that they can have access to reflected back to them. So, when we talk about banning and censorship—yes, it is about material texts being removed—but books are a gateway to understanding how one can survive in a world that is not built for their own survival. To extract that from someone’s life, I think, is to accelerate the potential that they might not survive or might not survive well.

Jacqueline, your work has been included on some banned book lists. What does it feel like to know that your work has been challenged, or that someone seeks to silence or erase your expression?

Jacqueline, your work has been included on some banned book lists. What does it feel like to know that your work has been challenged, or that someone seeks to silence or erase your expression?

Woodson: I didn’t know that my titles were being challenged and banned for a long time. You might notice—why am I not getting invited to that part of the country? Well, it’s because no one’s reading you. There is this insidious, much quieter erasure going on. You don’t know what’s out there until you go into those school libraries and go into those classroom libraries and look at those reading lists and see what’s not there.

Abdurraqib:The omission tells a story.

Woodson: It makes us realize how powerful words are, of course, and it also makes me sad about the erasure. It makes me sad that my words are not reaching the young people that I am talking to. I’ve met so many young people who could use the stories that we’re telling as mirrors, just as a way of seeing themselves in the world and understanding their own value.

I know that it is so intentional, the violence that this erasure is connected to—there’s so much violence in this country and in the world. We look at [these bans] and think, “Oh, it’s just books,” but it’s so much bigger and connected to so much else that’s going on. And at the heart of it, like always, are the children. It’s the children who carry the weight of the burden in this case. They walk into classrooms with empty shelves; they have no libraries at home, and they’re watching books get thrown into the trash. They try to get the books, and people are saying, “No, you can’t have this book in your hand.” It makes me very, very sad.

Abdurraqib: Some of this stuff is about infusing shame into young people who are curious. To take a book from a young person and say, “You can’t read that” or “You shouldn’t read that” at a young enough age, that infuses a shame into just the seeking of information or the seeking of pleasure. The books being banned—it’s not the fucking Communist Manifesto —these are kids’ books. These are books for young people.

|

Photo by Tommy Feisel ©2024 |

The thing that is really insidious about banning books—not just Jacqueline’s work, but since Jacqueline’s here, I’ll speak to the banning of her work—is that her work is speaking across generations. We can say that an 11-year-old Black child will find something worthwhile in one of Jacqueline’s books, and that same book is going to echo to a 30- or 40-year-old Black person. When the work is cross-generational, if you pull that initial pin out from the very beginning and say, “You, 11-year-old Black child, cannot access this,” that then will have an impact on the future generations that might not come in contact with that work.

You’re impacting an entire reading life and the lives that might come in contact with that reading life. So there’s an echo that goes far beyond just one person who cannot have this book.

Looking at that continuity across time, I think about us being part of a reading ecosystem—authors and publishers and librarians and booksellers and, of course, readers. Librarians serve as a kind of front line connecting with readers, and, in recent years, they’ve endured a great deal of the burden around these book challenges. They’re intercepting the efforts from would-be book banners. As authors whose work is protected by librarians, what do you want to say to them?

Woodson: You know, it’s interesting—I was talking to Emily [Drabinski], who lives in my neighborhood, and is the current president of the American Library Association. I think there’s a bit of fracturing happening in libraries, and that’s the first step of plunder.

I so deeply appreciate the work that librarians have done historically and continue to try to do, and we have to remember that united we stand.

I want to say thank you so much for the work. For the librarians who are getting challenged, they need other librarians who have their backs—those who are not getting challenged—to act as allies.

Abdurraqib: Librarians are doing mighty work, but they’re doing mighty work at a great cost.

I’m on book tour right now, so I’m bouncing around to a lot of places, and I talk to librarians often. A library in a small town should not have to fight on their own to be an entire center of support for the young people in that small town.

I talk to a lot of young writers, and to think about a young writer in, say, Marysville, Ohio, or a young, queer person raised in Ohio who is struggling to access literature that they would like to have outside of their home, they need a librarian funneling that work to them—and that librarian needs equal support. There should be a full ecosystem of support around the people who need it.

Today, if a librarian says, “I simply can’t do this anymore because it is brutal for me to be the lone person,” or, “I feel very alone,” we have to treat that with the same level of care and urgency that we treat getting the books into the hands of the people in need. ■

MORE FROM LJ ON THE IMPACTS OF CENSORSHIP

It Gets Personal: Four Voices

It Gets Personal: Four Voices

- BROOKY PARKS l Hard Victory for Equity

- SKIP DYE l The Making of an Advocate

- DR. CARLA HAYDEN l Renewing Our Commitment

- AMANDEEP KOCHAR l Sharpening My Resolve

On the Books: Library Legislation 2024

On the Books: Library Legislation 2024

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!