Civic Data Partnerships

By working with local experts on civic open data projects, libraries can become the heart of the smart city.

By working with local experts on civic open data projects, libraries can become the heart of the smart city.

Open data is a simple idea: Some datasets—such as information collected by a government about its citizens, or scientific data generated by government-funded research—should be publicly available and free for individuals and organizations to access and use. It’s one of the rare concepts to have bipartisan traction. In 2013, President Obama signed an executive order making open data the default for U.S. government information, and in January, President Trump signed the OPEN Government Data Act into law, requiring federal agencies to publish all non-sensitive data in machine-readable formats. States and cities have followed suit, with many launching local and regional open data portals.

When members of the public have access to government data, “the theory is...one, they can not only hold government accountable, they can engage and be a part of the process of solving community issues,” explains Lilian Coral, Director of National Strategy and Technology Innovation for the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, which has provided grants for several open data projects at libraries, and in November 2019 announced $1 million in funding for projects leveraging civic data to build more engaged communities. “Second, you can be an advocate, you can be a designer of a solution when you have more of that information at your disposal. Third…you can come up with entrepreneurial ideas.”

Prior to joining the Knight Foundation, Coral served as chief data officer for Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, leading the mayor’s directive on open data. She notes that, historically, users of open data are “civic technologists….software engineers, developers, coders who live in the community…. Civic hackers sometimes they call themselves—someone who already has the technical expertise and has a side curiosity,” as well as journalists and private companies. Uber, for example, might pull data regarding street closures, or a construction company might pull building and safety permit information. In addition, “a lot of city employees use the open data sets and data portals…. There really isn’t anything like a big data management system in most cities…and you’d be surprised how many private organizations struggle with this as well.”

Community members without a background in tech may not have much of an inclination to explore open data portals on their own, but there are other aspects to the movement. Corporations are collecting an enormous amount of data on people who use their services. While that data isn’t open, open data can be used to illustrate both the potential and the risk of such collection. Data analysis and visualization have become more prominent in academia, business, and journalism alike, presenting a new frontier in digital literacy. Open data projects offer libraries an opportunity to help patrons understand and participate in these growing trends, as well as, crucially, to help ensure that the broader community’s views and needs inform what hackers tackle. And partnerships with data-sharing and data-using organizations can strengthen the perception of the library as a key information hub.

|

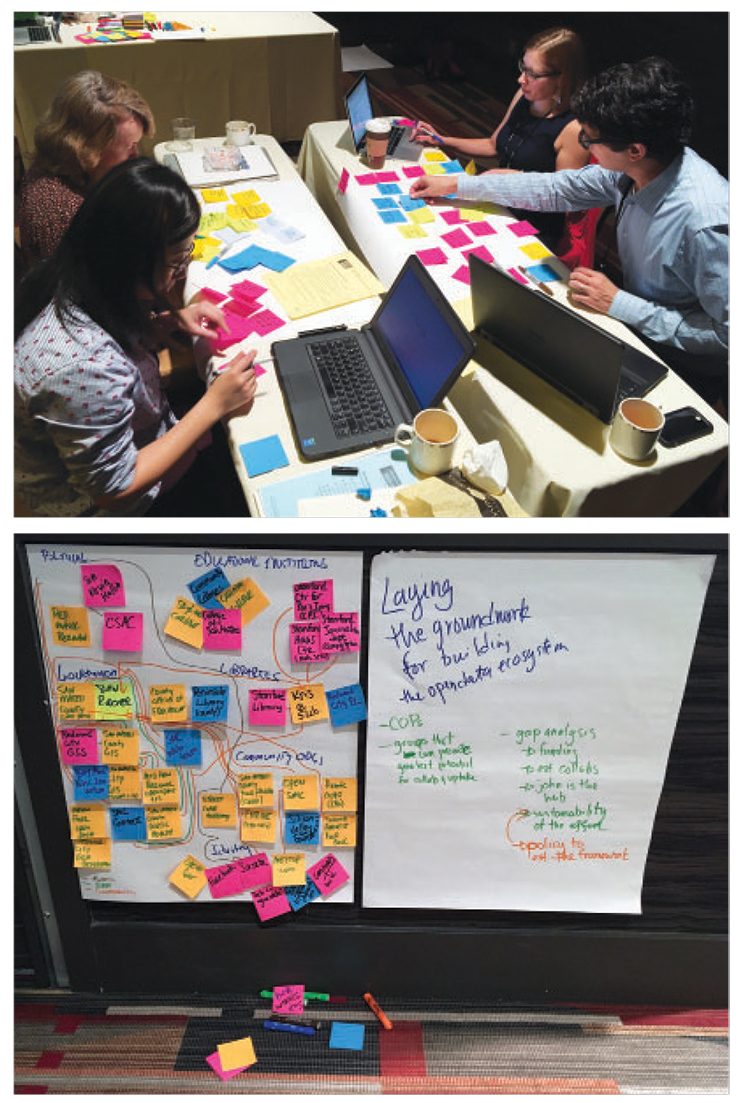

NEW COLLABORATION Civic Switchboard’s workshops in Atlanta and Las Vegas got librarians working with data

|

CIVIC SWITCHBOARD

“From the academic library side, researchers have a growing interest across different disciplines in using data and using different sources of data,” says Aaron Brenner, Associate University Librarian for Digital Scholarship and Creation at the University of Pittsburgh. “We know that students are very interested likewise in using data and gaining skills in data literacy, data analysis, data visualization…. There’s a lot of work and decisions being made by organizations like [regional data centers], oftentimes without the involvement of libraries or librarians. I really feel like there is both an opportunity—but almost an obligation—for libraries to be involved and to contribute their expertise and perspective in open data initiatives, particularly at the regional level.”

Brenner is one of the leads on a project called Civic Switchboard: Connecting Libraries and Community Information Networks. Funded with an initial grant of $224,761 from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), it’s a collaboration between the University of Pittsburgh, the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh (CLP), the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center (a regional open data portal), and the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership with support through the Urban Institute.

Civic Switchboard was designed around two convictions, according to the project site. First, healthy civic data ecosystems depend on partnerships—“the coordinated efforts of a variety of data intermediaries.” And second, there’s no one-size fits all model for those efforts. “Modelling at the national level must be done by capturing a wide variety of successful local practices.”

In 2018, the project hosted workshops in Atlanta and Las Vegas, bringing together librarians and representatives from research organizations and municipal governments to discuss topics such as data ecosystem mapping and opportunities for collaboration. Separately, in 2019, Civic Switchboard’s Field Project Awards provided nine libraries with stipends ranging from $3,000 to $9,000 for projects that involve partnering with local governments and other organizations to increase the role of libraries in local civic data ecosystems.

- The Alaska State Library worked with the state’s Office of the Governor to map Alaska’s data ecosystem.

- Charlotte Mecklenburg Public Library, NC, is partnered with the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute to create the “Civic Data Nerds United Council” which will inform local data literacy efforts and connect various stakeholders in Charlotte’s data ecosystem.

- Rice University’s Fondren Library is partnered with the Kinder Institute for Urban Research to provide data literacy workshops with Houston-area nonprofits.

- Pioneer Library System, NY, is working with the Substance Abuse Prevention Coalition of Ontario County, Council of Alcoholism and Addiction of the Finger Lakes, and Finger Lakes Prevention Resources Center Community to expand regional data sharing in support of substance abuse prevention.

- Providence Public Library, RI, partnered with NEXMAP, Chibitronics, and Wonderful Idea Company to develop teen-focused workshops that will enable these patrons “to create local data stories.”

- Queens Public Library, NY—in partnership with the Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics, NY Immigration Coalition partners, Center for Integration and Advancement of New Americans, Cidadão Global, DSI International, Haitian Americans United for Progress, and Polonians Organized to Minister to Our Community—trained a cohort of library staff to provide open data workshops in hard-to-count census tracts, partly in an effort to communicate the impact of the census on government funding and representation.

- The University of Baltimore’s Robert L. Bogomolny Library worked with the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance to create workshops to help neighborhood leaders use resources from the Baltimore Regional Study Archives and Baltimore Vital Signs Open Data, empowering locals to “improve quality of life in Baltimore neighborhoods.”

- St. Paul Public Library, MN, and the city’s Office of Technology and Communications raised awareness of civic data available on the city’s open information portal by hosting panel discussions and “community conversations,” as well as creating tools for families to learn about the portal outside of those events.

- The Western New York Library Resources Council partnered with the Butler Library at SUNY Buffalo State to identify open data resources via an environmental scan of western New York, and research how academic and public libraries can work with municipal governments and community organizations to raise awareness of these resources.

Last September, IMLS extended funding for the project with a supplemental grant that will support the project through early 2021, enabling Civic Switchboard to host another workshop and fund another round of Field Project Awards. Applications are being accepted this month. This year, the workshop and the awards will be more closely linked, with recipients using the workshop to help get their collaborative projects started. Case studies from all of these projects will be added to Civic Switchboard’s online guide (civic-switchboard.gitbook.io/guide), designed to help other libraries cultivate similar partnerships.

“Involvement in this [open data] space is a continuation of what libraries have been doing for quite a long time—helping communities discover and gain access to information,” says Nora Mattern, teaching assistant professor for the School of Computing and Information, University of Pittsburgh. “This is really a natural role for libraries.”

Toby Greenwalt, CLP’s Director, Digital Strategy and Technology Integration, adds that CLP became involved with Civic Switchboard because “we saw [open data] as a tool for building grassroots community advocacy. We’re a library system with 19 locations, each in different neighborhoods with very specific needs. We wanted to build tools for people in those neighborhoods to understand the changes that are happening around them and [enable them] to communicate and respond in kind. Whether it’s asking questions about the data in their neighborhood, or assembling new data to advocate for changes that are important to them.”

Civic Switchboard’s work is helping pave the way for other libraries to embark on similar projects, tailored to their own communities.

LOCAL ENGAGEMENT

Since 2015, the Toronto Public Library (TPL) has hosted a popular annual series of Open Data “hackathon” events, with locals of all ages using civic data sets to explore topics such as poverty reduction strategies or the impact of libraries on communities.

“We accept 70 to 90 participants, and we always have people waitlisted,” notes Carmen Ho, TPL’s Project Lead, Strategic Plan. “There is definitely a community out there that is interested in this type of collaboration.”

Like Civic Switchboard, TPL is a strong believer in cultivating partnerships with local experts for open data projects.

“The really fun thing about hackathons is that it’s a way to engage the community in idea generation,” says Ab. Velasco, Manager, Innovation for TPL. In 2015, “we’d never done a hackathon before, and honestly, I had never participated in a hackathon before. So, the way we went about organizing what seemed at the time [to be] a very daunting task was we reached out to community partners…. The groups that we worked with were the city of Toronto’s open data team, and an organization called the Open Data Institute of Toronto.”

By 2016, the hackathon on the City of Toronto’s poverty reduction strategy featured representatives from the Open Data Institute of Toronto; Civic Hall Labs; Councilmatic Toronto; Rentlogic; and the city’s Employment and Social Services and Social Policy, Analysis, and Research divisions. And last year, TPL hosted the Ontario open data community’s annual GO Open Data 2019 conference, including a full day hackathon following a day of panels and presentations.

Aside from these annual events, TPL’s board also adopted an open data policy in 2016, and the library launched opendata.tpl.ca, a portal hosting its own free datasets such as TPL’s top website searches, branch geolocations and profiles, circulation by intellectual level of material, programs by type, annual visits, and much more.

During the past decade, the library has partnered extensively with Richard Pietro and his meetup group Open Toronto. A leading advocate for Canada’s open data movement, Pietro’s work has included collaborating with the Ontario Ministry of Housing to develop new ways to create and publish open data sets, creating Open Data Iron Chef workshop events for university and secondary school students, and conducting the 2014 Open Government Tour, a three month cross-Canada motorcycle journey featuring 17 events in 17 cities to introduce the concepts of open data and open government to 2,000 Canadians.

With TPL, Pietro has hosted open data training workshops for library staff and patrons, as well as events including open data book clubs. Much like a regular book club, participants agree on an open data set from sources such as the Ontario government, Canada’s federal government, the Toronto city government, or in one case, TPL, and then spend a month analyzing it, data mining it, or generating data visualizations before gathering at the end of the month to discuss it. In place of author visits, the club often has someone who worked professionally with the dataset join the discussions.

Regarding his ongoing data literacy efforts, Pietro says “literacy is literacy. It’s not just about reading. It’s about understanding numbers. It’s also about privacy,” he adds, citing news about the United Kingdom’s contract with Amazon announced in December, which will allow the company to access healthcare information collected by the country’s National Health Service, purportedly to improve the Alexa voice assistant’s responses to questions about symptoms.

“We don’t know what the framework of that deal is…. As a data advocate, I believe in open data and privacy.” These concepts, he emphasizes, are not mutually exclusive, and citizens need to understand data well enough to denounce deals like this. “This is something people should be picketing outside city hall and Parliament and everywhere, because this is an atrocity,” he says. “By including data literacy and digital literacy training, the public library systems around the world are perfectly positioned to help communities learn those things, along with schools and other institutions.”

Ho says that the success of the hackathons and open data workshops at TPL has giving the library the sense that “people want to have a place where they can come and really tackle civic issues.” The library provides the space for that to happen, as well as the data literacy support to help locals learn to use open data portals and other tools.

Even one knowledgeable volunteer can help launch a program with a library’s support. And sometimes the most basic of library services can make a collaboration possible even for libraries with little or no data expertise on staff.

“Community organizers like myself need help if we’re going to advance any kind of conversation, especially around digital literacy, data literacy, and changing the culture of government,” Pietro says, describing how helpful TPL has been with his programs. “More than anything else, we need [public] space. Venue rentals are very expensive. Renting a projector and a screen, or a microphone and speakers can be expensive. Those are the kind of things that I now have access to” through TPL.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!