Everyone At the Table: Cedar Rapids Public Library Wins 2022 Jerry Kline Community Impact Prize

Conscious inclusiveness has earned Cedar Rapids Public Library the 2022 Jerry Kline Community Impact Prize. Honorable mentions go to New York’s Patchogue-Medford Library and Columbia, SC’s Richland Library.

When Cedar Rapids Public Library (CRPL) completed its previous strategic plan in June, library leaders, staff, and trustees took stock as they began to plan for the next four years. They’d built the 2018 strategic plan around three pillars: literacy, access, and inclusion. As they began to draft the new plan, all agreed: The institutional goals set four years ago will carry forward so the library, which serves a community of more than 130,000 in Cedar Rapids, IA, can build on its successes and continue to improve the community’s quality of life.

When Cedar Rapids Public Library (CRPL) completed its previous strategic plan in June, library leaders, staff, and trustees took stock as they began to plan for the next four years. They’d built the 2018 strategic plan around three pillars: literacy, access, and inclusion. As they began to draft the new plan, all agreed: The institutional goals set four years ago will carry forward so the library, which serves a community of more than 130,000 in Cedar Rapids, IA, can build on its successes and continue to improve the community’s quality of life.

Those overarching pillars may be ambitious, says Director Dara Schmidt, but CRPL has proved that ongoing progress is achievable. The board of trustees has confidence in leadership and staff, she notes, and the library is unafraid to think big.

What has made all the difference is that the library’s ideas, large and small, are developed with input not only from leadership and the board but from staff, residents—both patrons and non-library-users—and partners. CRPL has worked hard to make sure it is included in citywide planning. In turn, the library invites community and civic partners to its own table to help shape its strategy, ensuring that CRPL deliberately incorporates what the community wants and needs. That conscious inclusiveness has earned CRPL the 2022 Jerry Kline Community Impact Prize, developed in partnership with the Gerald M. Kline Family Foundation.

LAYING THE GROUNDWORK

CRPL’s definition of literacy, access, and inclusion encompasses the needs of a changing community. Cedar Rapids is the second-largest city in Iowa and has seen steady growth, including a recent influx of immigrants and refugees; according to a 2019 study from national nonprofit New American Economy, the immigrant population of Linn County, of which Cedar Rapids is the seat, increased by 61.8 percent between 2012 and 2017. Between 2000 and 2018, the number of BIPOC Cedar Rapids residents nearly doubled, from 8 percent to 15 percent.

The early strategic planning process involved “deep dives with our community partners to understand not just where they see the library in the community, but: What are their great needs? And what are their biggest hopes and challenges?” says Community Relations Manager Amber McNamara. “If we can have those conversations at the beginning and build that into the development of the design of these initiatives, then we’re going to achieve so much more.”

|

STRATEGIC TEAM Cedar Rapids Public Library’s (CRPL) Community Partners (l.-r.): CRPL Public Service Manager Todd Simonson, Mayor Tiffany O’Donnell, CRPL Board President Clint Twedt-Ball, CRPL Community Relations Manager Amber McNamara, CRPL Foundation Director Charity Tyler, CRPL Programming Manager Kevin Delecki, CRPL Board Vice President Monica Challenger, CRPL Director Dara Schmidt, City Finance Director Casey Drew, CRPL Materials Manager Erin Horst, CRPL Programming Specialist Mary Beth McGuire, City Parks and Recreation Director Hashim Taylor, City Community Development Director Jennifer Pratt, and CRPL Board Member Jade Hart. Photo by Savannah Blake |

Framing conversations is critical; a message may not change, but each stakeholder needs to hear it in a way that resonates, says Schmidt—“being thoughtful about language and forms of communication and types of reaching out, and which are the right tools to work with the right audience.”

“The library acts both as a central community center, providing safe spaces for all, and a mobile force bringing library expertise and resources out to the people,” says Jasmine Almoayyed, Kirkwood Community College vice president of continuing education and training services. “When the library does strategic planning, they don’t do it alone. They reach out to us and organizations throughout the community, seeking to identify areas of opportunity and challenge that affect us all. We feel connected to their goals because we were a part of designing them.”

And while the planning process is inspired by conversations outside of the library, it is largely refined through staff input, Schmidt notes. “People have these great big ideas, but then practically, how can you actually turn that into an operational, functional, achievable goal? That’s where our staff really shine.”

Whether refining organization-wide goals or imagining how they might be implemented, employees are involved at every step, “connected to the goals that were developed, so that it isn’t just something that is handed over to them at the end,” says McNamara.

PARTNERSHIPS FOR SUCCESS

CRPL has become a sought-after partner for civic initiatives, and a champion—and driver—of many of Cedar Rapids’ municipal objectives. When the city updated its comprehensive plan in 2021, Schmidt was asked to be on the steering committee. To help update goals around neighborhood planning and growth, transportation, green spaces and sustainability, economic development, and safety, city government leaders held community open houses at CRPL, enlisting the library’s outreach and social media channels to reach community members.

Schmidt has served as director for eight years, through three mayors, and notes that while elected officials and their politics may change, they have all supported the library. Because the nine-person board of trustees is appointed by the mayor, city allegiance strengthens the board as well. “That is essential work, to make sure that your community leadership really do like the library,” says Schmidt. “At their core, they believe in the work. That’s why we’ve been able to do so much.”

|

INPUT FROM EVERYONE Services are driven by leadership, staff, and community needs. Top-bottom: CRPL’s Downtown Library; Kevin Delecki represented the library at the IowaWorks Open Air Job Fair, along with the Mobile Tech Lab (MTL); kids making the most of the Summer Dare Everywhere reading program (l.); CRPL’s Meredith Crawford works the MTL Outreach program at a Hughes Park event (r.). Photos courtesy of Cedar Rapids Public Library |

Those accomplishments include the Opportunity Center at CRPL’s west side Ladd Library branch, a partnership with the United Way of East Central Iowa, Kirkwood Community College, Hawkeye Area Community Action Program, the city, Urban Dreams—a nonprofit working to remove barriers for underrepresented and underserved people—IowaWORKS, and several social service providers in the area. Partner staff members help patrons navigate services and connect with opportunities, offering guidance on everything from resume building and job searches to signing up for social services, finding affordable housing, and registering for classes.

|

LEADING THOUGHTFULLY CRPL Director Dara Schmidt. Photo courtesy of Cedar Rapids Public Library |

In fall 2021, CRPL collaborated with Collins Aerospace to hold the Girls in STEM Day. More than 100 eighth grade girls from area schools attended the full-day event, trying out the 3-D printer and laser cutter in the Maker Room to build a prosthetic arm for a child in need, discover how circuits work, fly a drone, and learn how to defend a system from cyberattacks. At the day’s end, some 80 percent of the participants said they would consider a job in engineering.

CRPL was one of 22 libraries across the country selected to participate in the Urban Libraries Council’s Building Equity: Amplify Summer Learning program funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Service (IMLS). Partnering with the Parks and Recreation Department, the library presented three weeklong middle school STEM camps in underserved areas of the city.

The library reaches out to local instructors as well as students, partnering with the Cedar Rapids Community School District to train teachers to use technology in new ways. This spring, almost 40 teachers from McKinley STEAM Academy, a local middle school designated as in need of improvement, participated in a professional development day at the library where they learned to use 3-D printers, green screen video technology, and Cricut cutting machines already in their school. “Students can use the technology to make engaging presentations,” English Language Arts teacher Dominique Brown says of the green screens, “putting themselves into historic scenes, books, or their own art projects.”

A RANGE OF LITERACIES

Childhood literacy needs begin early, and the library has identified organizations across the community, including Eastern Iowa Health Centers, Head Start, the Department of Human Services, WIC clinics, and local hospital birthing centers, to act as enrollment partners for Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library. These organizations enroll children on site, and the CRPL picks up and inputs the applications; as of June, 5,669 children—about 67 percent of the eligible population—were enrolled, and more than 4,300 have graduated from the program.

The community’s digital, functional, and technological literacy needs are top of mind as well. Cedar Rapids’ adult population struggled in the wake of the 2020 pandemic shutdown; unemployment was relatively low, but underemployment was pervasive, and many residents needed to improve their job prospects to stay afloat. Even before the pandemic, according to 2019 city data, 16.5 percent of city residents lived below the poverty level. The library saw an opportunity to step up workforce development efforts and address related needs. After studying data to pinpoint specific areas of need, CRPL realized that services had to meet patrons where they were.

The Mobile Technology Lab (MTL) was the result of an access-focused strategic plan committee of staff from across the organization. “I would not have come up with that on my own,” says Schmidt, who had envisioned tech classes in the library. “I thought they were going to go small, and they didn’t. They went big in a really different way.”

Funding for a mobile lab, including a vehicle and new staffing model, required a major ask—$155,000 over three years from the CRPL Foundation in community support, and another $25,000 from IMLS American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds to expand the work into the workforce development realm—and Schmidt grilled her staff team on the details before approaching the board. They had answers for everything, and their enthusiasm was contagious. “Every time I asked a question, they made me believe in it even more,” she recalls. “It is so much better than I could have ever imagined. That’s the beauty of letting go a little bit and letting other people shine.”

The goal was to introduce community members to technology, whether that meant learning to use e-readers, designing and printing a logo on a Cricut vinyl cutter, or recording a podcast. The Giacoletto Foundation, a local organization dedicated to funding education and lifelong learning, helped purchase the van, shelving, and modifications. Additional support came from Collins Aerospace, the Alliant Energy Foundation, ITC Midwest, and individual donations to the CRPL Foundation.

|

MEETING COMMUNITY NEEDS Top: volunteers Rachel Weishman (l.) and Supy Patel clean up a rooftop green space. Bottom: Patron Service Specialist Mark Reeves (l.) helps Julie Turner with a cover letter at the Ladd Library. Photos by Savannah Blake |

The MTL launched in May 2021, with tech tools and toys including laptops, e-readers, and Makey Makey kits and Ozobots for kids to explore. The technology on board is designed to roll into classrooms and community spaces, with programming provided by a grant-funded workforce support staff.

During the pandemic, because staff were unable to take it to schools and senior centers as originally planned, the lab instead collaborated with the city’s Parks and Recreation Department to visit six parks in low-income neighborhoods weekly throughout the summer. During the winter months the lab brought laptops and printers to larger-scale facilities such as rec center job fairs to help participants with job applications. MTL staff work with patrons one-on-one in partner locations such as the Willis Dady Homeless Shelter, providing resume assistance and job search help. In its first year of operations the lab reached 5,756 users at 128 different events in both branches, online, and nearly 20 locations around Cedar Rapids.

In the 2022–23 school year, the library will take the MTL to four elementary and middle schools ranked by the U.S. Department of Education as Needs Improvement or Priority, working to build relationships within the schools and then provide curriculum-based enrichment for students.

The MTL also serves as a pathway to the Maker Room in the Downtown Library. Starting in February, CRPL began offering one-on-one appointments for patrons to use the tools there, which include a laser cutter, 3-D printer, Cricut cutter, podcasting equipment, and other technology; more than 50 people have taken advantage of bookings.

“LITERACY IS SUSTAINABILITY”

Environmental sustainability is an explicit part of the library’s value statements and policies, but community sustainability is emphasized as well. Schmidt served on the Community Climate Leadership Team that developed Cedar

Rapids’ Community Climate Action Plan, approved by city council in 2021. This plan and its objectives align with library goals to support community equity, and the library’s community literacy initiatives have been incorporated into the city’s action steps. This means that “literacy is sustainability” is a phrase heard spoken by city management, and also that city gardens now have easily readable signage, virtual tours of local sustainability features include conversation starters for adults and children, and elementary schools have developed sustainability partnerships to include STEAM programming, literature connections, and story walks.

In 2022 the Downtown Library hosted the first Sustainable Economy and Transportation Conference, presented by Alliant Energy, the City of Cedar Rapids, and the Cedar Rapids Metro Economic Alliance. CRPL provided physical and virtual presentation space as well as an exhibit hall for the two-day event, highlighting the building’s LEED Platinum design. In thanks, Alliant Energy donated a vehicle charging station for the Downtown Library parking lot.

On a smaller scale, CRPL offers green resources to those who need them—during sustainability days, patrons can come by the library for reusable water bottles, LED lightbulbs, reusable flatware, and more. When the city called for reduced trash and consumption initiatives, the library led the way in 2019: Staff offices and seating areas have larger recycling cans but only small “tiny trash” bins for nonrecyclable garbage, a visible reminder to reduce waste.

EQUITABLE ACCESS

While putting together the 2018 strategic plan, the board chose to remove the word “equality” and replace it with “equity,” to guide the library toward redressing unbalanced systems. That shift in focus, says Schmidt, means that “every time we make a decision about how to implement a literacy, access, or inclusion strategy, we go back to equity and say, ‘Have we met this need? Have we looked at where there are parts of our community that have been left out before? And have we concentrated on it?’”

Library research revealed that many residents depended on CRPL for access to informational and technological resources but had trouble accessing physical branch locations; nearly one third of respondents to a 2018 telephone survey said that they hadn’t used the library in the previous year. This information drives decisions from outreach planning to choosing where to take the Mobile Tech Lab, and services to homebound patrons and seniors have been expanded. It also helped convince the board to go fine-free in May 2021, restoring library access to more than 16,000 residents.

|

IMAGINATION TEAM Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library partners collaborate for early childhood literacy. Top row, l.-r.: Schmidt, Young Parents Network Director Alejandro Pino, Greater Cedar Rapids Community Foundation Senior VP Karla Twedt-Ball. Bottom row, l.-r.: CRPL Programming Manager Kevin Delecki, Foundation Director Charity Tyler. Photo by Savannah Blake |

WELCOMING NEW AMERICANS

The city has become a destination for immigrants and refugees via both primary and secondary migration (when residents relocate from the U.S. state where they first settled within the first nine months), with an influx of arrivals from Afghanistan, Burundi, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The library has worked with the city to add welcoming resources online, including links to community resources for housing, utilities, and immigration services—but CRPL’s in-person inclusion work has flourished outside its walls as well.

In 2018 Cedar Rapids, in conjunction with the Cedar Rapids Metro Economic Alliance, was invited to participate in Gateways for Growth, which offers cities the opportunity to receive support from the American Immigration Council and Welcoming America to improve immigrant inclusion in their communities. Thanks to this program, the city began participating in Welcoming Week, a national initiative that encourages local support and efforts to engage new Americans, with the library leading language and programming.

Eventually, local government opted to create a plan with the group Inclusive ICR to grow diversity and inclusion in the region’s workforce. As part of this initiative, CRPL led the city’s 2022 Welcoming Week campaign, Welcome Is Our Language, which offers resources from recreational and cultural institutions and information for entrepreneurs.

The annual Community Cultural Celebration and Expo at CRPL’s Downtown Library, presented in partnership with the Cedar Rapids Civil Rights Commission, has grown in response to community needs in the five years since the city first asked the library to help develop it. With a planning committee of representatives from community groups such as Legion Arts, Refugee and Immigrant Association, United We March Forward, Tanager Place, and others, the event brings residents together for a day of music, dance, art, and an exhibit hall for local cultural and service organizations.

EMPOWERING THE INCARCERATED

CRPL partners with Linn County and the Iowa Department of Corrections on several programs.

Staff deliver a diverse selection of books to teens at the Juvenile Detention Center and facilitate weekly book discussions. These have been recorded and shared virtually as an audio program developed by Programming Librarian Meredith Crawford called “Be Heard,” available to the public (with all identifiers removed to protect participants). Programs centering youth experiencing incarceration lets them see themselves as integrated into larger systems, the programmers feel—at school, at home, and within the community—offering empowerment and validation.

Another partnership with the county, city, and Iowa Legal Aid has produced Expungement Clinics and Resource Fairs, which help people remove criminal case records that can pose barriers to housing, employment, or education, and provide information on assistance programs and resources.

CENTERING STAFF VOICES

Inclusion, in the library’s playbook, also means consistent communication at all levels. “Dara cares about people, and she cares about the relationships that she has with people,” says Programming Specialist Mary Beth McGuire.

All staff, no matter what their position, job description, or hourly status, are given the opportunity to participate in groups that implement library strategies. The only qualification necessary is a passion for the work involved—because “you know things that I don’t know, and you care about things that I don’t care about,” says Schmidt. This ensures that as many departments as possible are represented, and encourages employees across all roles to grow and develop leadership skills.

“We say to staff, ‘Here’s what we want to do, here’s the big picture, here’s the strategy,” Schmidt explains. “Is it something that you’ve done any work with outside of the library, maybe volunteering through your church or through a food pantry? Or is it just something that you really care about, because your kid or your uncle or your best friend has struggled with this? It doesn’t matter the reason, and it doesn’t matter what your position is, or how many hours you work at the library—if this is something you care about, you get to be on that strategic team, you have a voice in this process, because your passion gets to drive it.” The Mobile Tech Lab was one such idea.

“We have in our contract that people can apply to go to training twice a year, and those applications come from every department, from every job description,” says McGuire. “It’s not just management and a couple of librarians that go to trainings. Anyone can go, they just have to ask and have a good reason.”

Empowered staff can then go out into the community and represent the library in a wider range of scenarios than leadership could accomplish alone. And engaged employees stay and rise through the ranks; over the past three years, 90 percent of leadership roles have been filled by internal candidates.

Schmidt has been outspoken in her support of the staff union, Communication Workers of America, and McGuire, the library’s chief union steward, no longer refers to the longstanding labor agreement as the union contract. “I say it’s our contract, because it’s a contract that I signed and Dara signed and the president of the board signed. We all work together on it and it’s a real negotiation.”

Communication lines with trustees are also clear, prioritizing what the board needs to know to make good decisions—from the section of the monthly board packet titled “Great Stories,” highlighting meaningful interactions between staff and patrons, to the detailed numbers backing up proposed initiatives. “When our board listens to us, they’re always going to have a lot of questions, but they appreciate the fact that we come with that really fully formed plan,” says McNamara. “So much of what we do is data-driven.”

“It starts with a high high level of trust,” says board President Clint Twedt-Ball. “We are, as a board, able to operate at that strategic level and set priorities in place in collaboration with the staff, and we have a lot of trust in Dara. So we know that once a plan is created, she’s going to go out there and implement it. We trust that her values align with the trustees’ values, and she’s going to make good decisions.”

And while CRPL hasn’t weathered the intense book challenges that some libraries in the region have seen, the board’s stance is clear, says Twedt-Ball: “We believe that there should be a wide diversity of opinions and views expressed by the library, and we’re supportive of that. If you want to keep your kids away from it, that’s up to you as a parent, but we’re not going to stop offering those kinds of things.”

|

HELP IN HARD TIMES Library employees worked alongside other city staff to distribute supplies—diapers, paper goods, food, and more—at Neighborhood Resource Centers after the derecho. Photos courtesy of Cedar Rapids Public Library |

COPING WITH DISASTER

The library team was used to thinking on its feet, moving quickly to support students who needed internet access during the pandemic, shifting the Mobile Tech Lab’s access model to conform to safety mandates—and making sure not a single employee lost their job during the COVID shutdown.

But nothing prepared the community for the devastating derecho—a storm that causes hurricane-force winds, tornadoes, heavy rains, and flash floods—that struck Cedar Rapids in August 2020, bringing wind speeds of 140 mph and causing extensive damage throughout the city. Homes and businesses were torn apart, and 70 percent of the area’s tree canopy was obliterated in less than 30 minutes. Many were without power for weeks and had no internet access for longer.

In the first hours after the derecho passed, despite the lack of any way to communicate with each other, people began showing up outside the Ladd branch. “The library is a place you can get access to resources during normal times,” notes McNamara. “So when there’s nowhere else to go, and you don’t know what to do, that’s the kind of place you’re going to go.” With no power and a damaged roof, the building was unable to open its doors, but the parking lot became an ad hoc disaster response service point and was designated a Neighborhood Resource Center.

In the following days, staff set up charging stations outside the library as soon as power was restored. Despite having emergencies of their own at home, employees showed up; they were dispatched to Resource Centers around Cedar Rapids, handing out supplies and helping at the tree debris drop off site as the city began cleanup efforts.

Staff gave out food, water, diapers, personal care items, and cleaning supplies. “People were coming who were living in tents,” recalls CRPL Administrative Assistant Jessica Musil. Two local hospitals purchased a generator to set up in the library parking lot so residents could charge medical equipment. When three high school buildings were so damaged that they could not open, library meeting rooms served as a school location for the entire semester for students who didn’t have home internet service.

That difficult time, says McNamara, deepened the library’s connection with community partners, largely owing to staff’s willingness to step up and CRPL’s preparedness for times of crisis. “If we didn’t have those skills before the derecho, it would have been a very different experience,” she says. “But we had built teams that knew how to communicate with each other, that had worked a lot on intentionally being there for each other.”

While employees were responding to community needs, the library continued to be mindful of its staff. “We had to, because everybody was broken. People were just so tired, so hot, and so miserable,” says Schmidt. “We’ve learned to be even more trauma-informed in our internal communications and how we work with each other.”

That internal resilience was put to the test again this July, when a fire broke out in a light fixture above the Downtown Library’s Commons area. The sprinkler system activated and the fire was quickly extinguished, with no injuries, but the library was forced to close until September 1 for cleaning and repairs. Once again, says McNamara, “our staff were amazing,” relocating to alternate locations and stepping up outreach until they could return to the building.

Yet despite this string of challenges, CRPL has been reliably present for its community when it was needed—and Cedar Rapids has returned the favor, over and over.

After the derecho, in recognition of the library’s place at the center of vulnerable neighborhoods, the city and county allocated $8–10 million in ARPA funds toward a new, permanent facility in Cedar Rapids’ Westdale neighborhood. Located a few blocks from the existing Ladd Branch—currently housed in a rental space—the new library will also be a regional service center, designed to support resiliency, welcome new immigrants, and serve as a neighborhood anchor.

In addition to federal support, the new facility will be helped along with some local love. In 2020, a Cedar Rapids woman, Nadine Sandberg, died just short of her 103rd birthday. She told her lawyer that she wanted to give her estate—more than $1 million—to the library because it was a place that would “do good things with it.” Thanks to Sandberg’s gift, what would have been a 10-year capital project is scheduled to be completed in four.

“That really doesn’t happen in most places and most professions,” marvels Schmidt. “But it does happen in libraries, and that is incredibly moving, incredibly humbling. Also, what an absolutely astounding possibility—to be able to have that opportunity to do something for your community because somebody else believed in you.”

HONORABLE MENTIONS

PATCHOGUE-MEDFORD LIBRARY l NEW YORK

Danielle Paisley | Library Director

The Patchogue-Medford Library serves 51,903 residents through an emphasis on community engagement. Employees meet weekly to share what events they attended, what they learned, and what the library can do with that information to connect local resources.

To serve the growing local Latinx population—46 percent of students in local schools—the library recruited Spanish speaking staff at all levels, including leadership, and prioritized helping recent immigrants with daunting governmental bureaucracy such as applying for a driver’s license. Local village, county, and school district elected officials rely on the library for advice on effectively meeting the needs of Latinx constituents.

When a hate crime was committed against an Ecuadorian immigrant in 2008, local officials wanted to do more to combat racism and discrimination. They turned to the library to take the lead on initiatives to create a safer and more inclusive community, such as the Language Café, where local teens from English- and Spanish-speaking backgrounds come together weekly to practice language skills. More than 10 years ago, a local Spanish-speaking parent approached the library seeking a sense of belonging. The library worked with her to develop Madres Latinas, to help Spanish-speaking moms navigate and tap into resources in the community.

The Jovenes teen group is run by the Spanish Outreach and Teen Services Departments. Library staffer Lizbeth Zichay, who immigrated in her teens, knew the challenges many face in learning not only English but the culture and expectations of U.S. high school, often while working in family businesses or childcare. Zichav recommended a social group for newly arrived immigrant teenagers, incorporating outdoor play, soccer, and foods from members’ cultures.

The library partners with the Stony Brook Small Business Development Center to provide bilingual help. Other services include English classes, citizenship instruction, bilingual one-on-one financial aid and college application assistance, and bilingual programming for all ages.

In “Everybody Eats,” people from all walks of life share a meal at the library. Indeed, food drives many of the library’s successful outreach efforts. The library worked with the village to host food drives, coordinating local food pantries and assistance agencies with a bi-weekly Zoom that turned into a non-perishable food shelf at the library both stocked and used by patrons. The local Special Education PTA provides fruits, vegetables, and dairy weekly, and donated a refrigerator. The library hosts programming at restaurants and provides children’s activity placemats. With non-profit Harmony Cafe, the library offers workshops on nutrition, cooking and healthy eating on a budget for low-income families and seniors.

Not resting on its laurels, the library’s next steps include further staff training on equity, and diversity audits of collections and services.—Meredith Schwartz

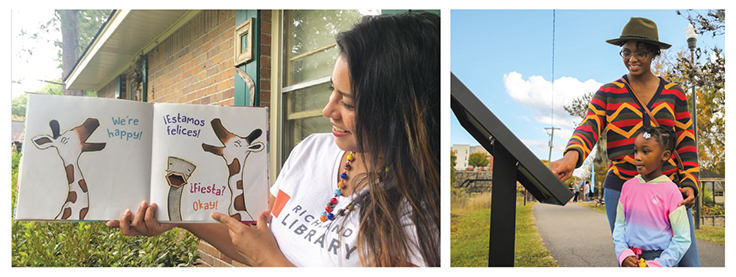

RICHLAND LIBRARY l COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA

Melanie Huggins | Executive Director

Richland Library’s (RL) community engagement is deep and strategic. When COVID more than tripled local unemployment, 29 staff members became certified career coaches and assisted 3,400 job seekers, promoted by Bank of America grants. Google and the American Library Association funded Entrepreneurial LaunchPad, featuring an Entrepreneur-in-Residence, equipment library, and targeted programming. Three full-time social workers, supported by local foundations, have helped 16,554 patrons access resources and benefits. A partnership with the county sheriff led to gun safety programs and free gun locks. RL’s HomeSpot Initiative provided hotspots to over 700 households in partnership with T-Mobile, as well as public housing and recreational commissions.

Beyond its service area, RL led the fight against a state budget amendment that would have denied public libraries funding if they refused to certify they had no materials appealing to “prurient” interest in children’s sections. RL is also embedded in statewide efforts to improve literacy, creating and hosting an annual symposium to train 350 leaders for Read to Succeed camps.

The library’s Let’s Talk Race team, featured in the June 2022 issue of LJ, has facilitated conversations for more than 2,000 attendees so far; RL is creating an open-sourced curriculum and toolkit for other libraries.

RL’s Chief Equity and Engagement Officer drives internal and external equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) initiatives, including staff training and the Una Voz team, dedicated to Spanish-speaking customers. RL raised its minimum wage to $15, instituted eight weeks of paid Family Medical Leave, and offers Project Play, in which staff can spend up to an hour a week playing. A nine-month leadership development program has 106 graduates, 43 percent of whom have been promoted. The EDI Council, created in 2020, mentors BIPOC staff, examines programs and processes through an EDI lens, and more. Intentional recruiting and removing the MLIS requirement for management has increased BIPOC staff from 30 percent in 2013 to 42 percent, and from 17 percent of managers to 40 percent.

RL used human-centered design to develop its Library as Studio model, and continues to apply it in the community. A 2017 IMLS grant let RL develop Fresh Food Fresh Thinking: Staff worked with high school students, architects, and teachers to envision a hybrid space housing a library and farmer’s market, and developed recommendations for emulators. In 2017, RL created Do Good Columbia to share the methodology to solve community problems. In 2020, the library partnered with the Midlands Business Leadership Group and EngenuitySC on a human-centered design study of barriers to recruitment and growth of BIPOC employees. In 2023, Do Good Columbia 2023 will focus on vulnerable citizens and how the community coordinates to help those in crisis.—Meredith Schwartz

The Jerry Kline Community Impact Prize recognizes the public library as a vital community asset. The prize seeks to honor a library that has achieved this recognition to the highest degree through a strong reciprocal relationship with its civic stakeholders and community.

The Jerry Kline Community Impact Prize recognizes the public library as a vital community asset. The prize seeks to honor a library that has achieved this recognition to the highest degree through a strong reciprocal relationship with its civic stakeholders and community.

To honor its exemplary record, Cedar Rapids Public Library will be presented with $250,000 from the Gerald M. Kline Family Foundation. A gala celebration is planned for the LibLearnX conference, Jan. 27–30, 2023, in New Orleans

We thank the following external judges who helped inform the final decision:

NATE COULTER | Executive Director, Central Arkansas Library System, 2021 Jerry Kline Community Impact Prize winner

ED GARCIA l Director, Cranston Public Library, RI, 2020 Jerry Kline Community Impact Prize winner, 2010 LJ Mover & Shaker

MARC A. OTT l Executive Director, International City/County Management Association

RIVKAH SASS l Former Director, Sacramento Public Library, inaugural Jerry Kline Community Impact Prize winner, 2002 LJ Mover & Shaker and 2006 Librarian of the Year

Also serving as judges were: Leslie Straus, Library Grants Director, Gerald M. Kline Family Foundation and Meredith Schwartz, Editor-in-Chief, LJ.

For more information, see libraryjournal.com/communityimpact

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing