How Serious Is America’s Literacy Problem?

The first step in solving a problem is seeing it clearly. This article, part one of an ongoing series, defines the broad scope and depth of the literacy crisis in the United States, among both children and adults. Future installments will address the complex ecosystem of schools, government agents, nonprofits, and more that are tackling this challenge; survey librarians on what they are doing to improve literacy in their communities; and highlight case studies and best practices of those making a difference.

The first step in solving a problem is seeing it clearly. This article, part one of an ongoing series, defines the broad scope and depth of the literacy crisis in the United States, among both children and adults. Future installments will address the complex ecosystem of schools, government agents, nonprofits, and more that are tackling this challenge; survey librarians on what they are doing to improve literacy in their communities; and highlight case studies and best practices of those making a difference.

The first step in solving a problem is seeing it clearly. This article, part one of an ongoing series, defines the broad scope and depth of the literacy crisis in the United States, among both children and adults. Future installments will address the complex ecosystem of schools, government agents, nonprofits, and more that are tackling this challenge; survey librarians on what they are doing to improve literacy in their communities; and highlight case studies and best practices of those making a difference.

|

See also: |

According to the International Literacy Association, there are 781 million people in the world who are either illiterate (cannot read a single word) or functionally illiterate (with a basic or below basic ability to read). Some 126 million of them are young people. That accounts for 12 percent of the world’s population.

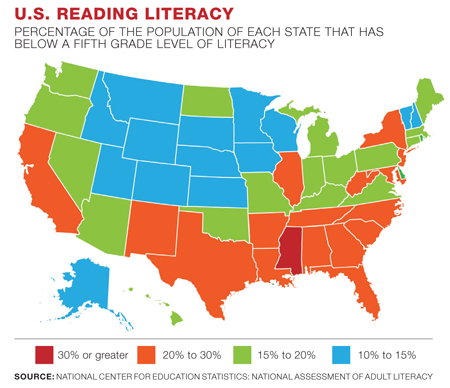

This is not just a problem in developing countries. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES), 21 percent of adults in the United States (about 43 million) fall into the illiterate/functionally illiterate category. Nearly two-thirds of fourth graders read below grade level, and the same number graduate from high school still reading below grade level. This puts the United States well behind several other countries in the world, including Japan, all the Scandinavian countries, Canada, the Republic of Korea, and the UK.

The NCES breaks the below-grade-level reading numbers out further: 35 percent are white, 34 percent Hispanic, 23 percent African American, and 8 percent “other.” Nor is this a problem mostly for English Language Learners. Non-U.S.-born adults make up 34 percent of the low literacy/illiterate U.S. population. New Hampshire, Minnesota, and North Dakota have the highest literacy rates (94.2 percent, 94 percent, and 93.7 percent respectively), while Florida, New York, and California have the lowest (80.3 percent, 77.9 percent, and 76.9 percent respectively).

WHY IT MATTERS

WHY IT MATTERS

The risks to people who can’t read or can barely read are significant, including:

HEALTH The American Journal of Public Health reports that the inability to read and understand health information accounts for $232 billion spent in health care costs each year. It also affects life span. A study by Harvard University found that people who had at least 12 years of education had a life span a year and a half longer than those with less education.

It’s not just that low literacy leads to poverty and poverty to poor health care. Even after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, the relationship between reading level and health remains. Studies have linked low literacy to problems with use of preventive services, delayed diagnosis, adherence to medical instructions, and more.

EMPLOYMENT The National Council for Adult Learning points to annual costs of $225 billion in nonproductivity in the workforce, crime, and loss of tax revenue due to unemployment tied to low literacy. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has data showing a strong relationship between educational attainment and employment.

POVERTY The National Institute of Literacy says that 43 percent of adults with the lowest literacy levels live in poverty. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the official poverty rate in 2018 was 11.8 percent, down slightly from 2017. But 17.6 percent of Hispanic people and 20.8 percent of African Americans were classified as being in poverty, much higher than the average, and both groups saw an increase from 2017. Literacy and income are tied closely together, though race-based discrimination affects Hispanic people and African Americans in the employment market, making it harder to earn incomes comparable to white people even at equivalent educational levels.

GENERATIONAL LITERACY Adult poverty in turn impacts children; 61 percent of low-income families have no children’s books in their homes, which affects the child’s ability to develop the skills to begin reading on their own. The Annie E. Casey Foundation reports that 68 percent of fourth graders in the United States read at a below proficient level, and of those, 82 percent are from low-income homes. The National Bureau of Economic Research says 72 percent of children whose parents have low literacy skills will likely be at the lowest reading levels themselves. The pattern sets in early: the American Library Association says a child who is a poor reader at the end of first grade has a 90 percent chance of still being a poor reader at the end of fourth grade.

CRIME The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has data showing that 75 percent of state prison inmates are either classified as low literate or did not complete high school. The Literacy Project Foundation reported that three out of five people in prison can’t read, and 85 percent of youth offenders struggle to read. A study by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy found that providing general education to people in prisons reduced recidivism by 7 percent.

Many of these statistics are related, says Sharon Darling, president and founder of the National Center for Families Learning (NCFL). “There have been all kinds of initiatives to deal with literacy, by governors, foundations, school boards, and we’ve seen some progress. But these things are the petals of a flower, and literacy is the stem.”

Darling founded NCFL 30 years ago to work for literacy not only with children but also the adults in the family. The ideas that parents could help children and that generational literacy was a problem weren’t necessarily novel, but there were unexpected findings. “In the first year, we found 50 percent of parents in our programs got better jobs. We weren’t aiming to improve employment, but quickly realized we needed to look at this.” She points to a 2010 National Institutes of Health study that found that improving a parent’s—specifically a mother’s—literacy outweighed any other method of improving literacy.

Parents who are struggling with literacy are also more likely to struggle with employment and income and, in turn, pass those struggles down to their children. Darling says that working with the parents helps both them and their children. “These are parents who feel so defeated. Their children start having problems in school, and the parents think, ‘That’s what happened to me, too.’ They thought they were stupid.”

Far from it. Darling tells the story of a mother who lived with her children in a car who enrolled in an NCFL program and eventually went on to earn two master’s degrees. Each of her children also hold master’s degrees. Another family lived in a garage, but the parents were able to earn GEDs and go on to community college. Climbing out of illiteracy and poverty allowed them to help their children, who then both received full rides to UCLA. One is working on a PhD.

Far from it. Darling tells the story of a mother who lived with her children in a car who enrolled in an NCFL program and eventually went on to earn two master’s degrees. Each of her children also hold master’s degrees. Another family lived in a garage, but the parents were able to earn GEDs and go on to community college. Climbing out of illiteracy and poverty allowed them to help their children, who then both received full rides to UCLA. One is working on a PhD.

While NCFL has served more than 20 million families in its 30 years, Darling says much more can be done. “The achievement gap is still stubborn for children in poverty. The biggest change asset is the home and family. We’ve not taken advantage of resources for that. We have to look deeper.”

STALLED PROGRESS

At first glance, things have improved drastically over the past two centuries. Our World in Data, an online publication that tracks global problems, notes that only 12 percent of the global population could read in 1820, while today 12 percent can’t read. That impressive turnaround helped reduce inequalities within industrialized countries, including the United States. In 1870 in the United States, more than 75 percent of communities of color were illiterate, compared to not quite 25 percent of the white population. By 1980, those rates had come close to closing the gap.

But while the literacy gap improved, overall literacy has remained stagnant and, in the short term, possibly declined. In 1992, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) began testing students in fourth and eighth grades every other year. The 2019 results showed an increase in literacy from those first tests in 1992, but also marked a slight decline from the testing done in 2017. The 2017/2019 data comprises 17 states/jurisdictions that had scores decrease, 34 states/jurisdictions that stayed the same as in 2017, and one state (Mississippi) that showed an increase in literacy rates.

All racial/ethnic groups saw improvement from 1992. But when compared to 2017, white and African American students both scored lower, while Hispanic students did not have a noticeable change.

In 2010, the NCES began tracking the adjusted cohort graduation rate (ACGR) for public high school students. The ACGR is defined as the cohort of first-time ninth graders in a particular school year, with that number adjusted by any student who transfers in or out of the class after the ninth grade. The percentage of the students in this cohort who graduate within four years is the ACGR. In its most recent reporting from 2016–17, the adjusted cohort graduation rate of public high school students was 85 percent, the highest since measurements began. Some 91 percent of Asian/Pacific Islanders, 89 percent of white people, 80 percent of Hispanic people, 72 percent of American Indian/Alaska Natives, and 70 percent of African Americans graduated from public high schools that year.

EARLY ACCESS

EARLY ACCESS

Getting children to read at their grade level is, as mentioned above, a critical factor in setting them up for future literacy. Risk factors include whether the family has access to books and whether children are being read to before they can read themselves. The National Institute of Literacy reports that only about half of children are read to daily by family members. The reasons could be myriad, tied in part to poverty and lack of literacy in the adult members of the household.

Pew Research Center found in 2019 that 27 percent of U.S. adults said they had either not read or completed a single book in the previous year. Adults who had only a high school diploma or hadn’t completed high school were far more likely to be nonreaders (44 percent) than those who had some college (22 percent) or completed college degrees (eight percent). Lower educational attainment also correlates with lower rates of smartphone ownership, and smartphones are increasingly used for reading ebooks.

Household income also played a role, with those at the lowest income levels the most likely to not have read a book. The study also found variations among different racial/ethnicity categories: 22 percent of white adults, 33 percent of African Americans, and 40 percent of Hispanic adults said they had not read or completed a book. In the case of Hispanics, location and origin is key: 56 percent of Hispanic people not born in the United States were more likely to not have read a book, compared to 27 percent of those born in the United States.

This could be related to language challenges faced by immigrant students. NPR reported that English language learners (ELLs) lag in academic achievement. Only 63 percent of ELLs graduate from high school, and of those who do, only 1.4 percent take college entrance exams.

NPR also found that many ELLs are concentrated in schools with performance issues whose teachers are either poorly trained or not trained at all to work with this population. Often in those cases, literacy begins to lag almost immediately. When reading is hard and school performance suffers for it, students are less likely to read for pleasure. The National Institute of Health reports that ELLs may be more likely to have teachers with less experience, and they may also attend schools with more lower-income students and fewer resources.

Illiteracy and low literacy is among one of the most dire issues facing policy makers, educators, and communities across the nation, with adverse consequences that can ripple down through generations, affecting everything from employment prospects to health care. Though the statistics are alarming, solutions are in reach. Solving the literacy crisis will require creative collaboration among various stakeholders—and libraries have a crucial role to play.

Part two of our series will appear in the June issue of LJ, focusing on the literacy ecosystem: mapping the infrastructure of the landscape of who is working on literacy, including foundations, corporations, and charities, as well as governmental entities such as schools and libraries. Part three will appear in the August issue, examining literacy in practice and how libraries and librarians are addressing the crisis. Part four will appear in the October issue, spotlighting innovative best practices, case studies, and a look ahead at what’s next.

Amy Rea is a freelance journalist living in Minnesota.

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing