Tackling Trauma in Frontline Workers

As frontline public library workers experience increasing levels of trauma on the job, a recent report and forum consider how to help disrupt the cycle.

As frontline public library workers experience increasing levels of trauma on the job, a recent report and forum consider how to help disrupt the cycle

As frontline public library workers experience increasing levels of trauma on the job, a recent report and forum consider how to help disrupt the cycle

Trauma among library workers is not a new phenomenon. Any organization focused on helping the public—such as those in health care, social work, and education, to name a few—can generate high levels of stress for those who do the work. Libraries, however, are seeing increasing pressure to step in where other services are lacking, a situation amplified in recent years by the COVID pandemic and elevated social tensions around race, gender, and sexual orientation.

While the recent focus on trauma-informed librarianship has helped build awareness of—and compassion for—what patrons experience, it doesn’t necessarily address what library employees are going through. Exposing frontline staff to further stresses without attending to their own can lead to secondary trauma and empathy burnout. Workers find themselves contending with material scarcity, housing and food insecurity, addiction, racism, and other forms of bias, violence, isolation, and other community issues that they are unprepared—and often unsupported—to face.

Urban Librarians Unite (ULU), a grassroots library advocacy organization, has its roots in challenging times. Founders Christian Zabriskie and Lauren Comito, the current executive director, incorporated ULU in the wake of the 2010 recession, when libraries and staff alike were feeling the pain of budget cuts and layoffs. ULU went on to stump for library funding and resources for immigrants, refugees, and libraries hit by natural disasters. Since 2013, ULU has produced an annual conference that spotlights the needs of frontline library employees.

“Every time we got together, library workers would share their most recent awful thing—kind of like trading war stories,” Comito tells LJ. ”It reached a point where I felt like we were failing to take care of each other as a profession and the only way to fix that [was] to identify it and start working.”

In 2020, ULU, in collaboration with the New York Library Association and St. John’s University, received an Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Laura Bush 21st Century Librarian Grant to investigate the causes and outcomes of trauma in frontline urban library workers and produce an in-person forum to begin investigating solutions. The study was delayed and redesigned due to the pandemic, but the resulting literature review, survey, focus groups, and report offer deep insights into what library staff are experiencing, and the results of the convening offered a range of ideas for ways administration and employees can work together to address them.

IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEMS

As project leads, Comito and Zabriskie—along with a team of research fellows—read what was available on the subject before the conversations began. The team found multiple factors that combine to make trauma among library workers both ubiquitous and under-acknowledged.

Research on trauma in public library work is not yet as deep as in similar fields, they note. There are no databases or lists that quantify violent or criminal events in libraries; the American Library Association (ALA) does not track incidents in libraries, and there is no easy way to follow national library crime statistics.

Even more damaging is the sense of isolation on the part of library workers experiencing trauma. Repeatedly—in survey responses, focus groups, and the forum—the same comment was repeated by participants: They thought they were the only ones experiencing a difficult event or particular stressor. “This document is a testament that they are not alone,” write Comito and Zabriskie.

The survey was distributed in August and September 2021. It garnered 435 responses from public library staff across the United States, from pages to executive directors. Half were librarians, and a majority—78 percent—self-identified as women. Most respondents had worked in libraries for at least five to 10 years, and the majority indicated that they felt daily stress on the job.

The specific traumatic events described by the 255 respondents who chose to do so included verbal abuse, physical assault or abuse, harassing or inappropriate behavior, situations relating to patrons’ use of drugs or alcohol, sexual assault or harassment, secondhand trauma experiences, or issues involving patrons’ mental health or mental illness. Sexual harassment and racial abuse, from patrons but also colleagues, supervisors, and board members, is widespread.

|

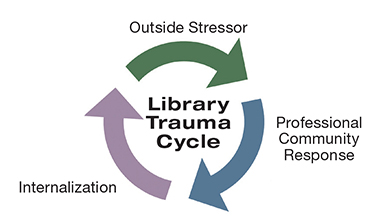

CYCLE OF TRAUMA The three-stage cycle graphic offers a model for trauma’s progression and the stages where it can be interrupted |

Safety is a major issue. Witnessing and experiencing violence in public libraries has become increasingly common, and many workers feel that the security provided in their buildings is inadequate. More than two-thirds (68.5 percent) of survey respondents reported experiencing violent or aggressive behavior from patrons, and a more than a fifth (or nearly a quarter)—22 percent—said they experienced it from coworkers.

Focus group participants noted that library school often does not prepare librarians for the work they will face, and frequently, given the difficulties of getting a job, people are inclined to settle for the situations where they end up. Despite not having been trained to serve populations in crisis—or even having the desire to do so—many urban library employees find themselves serving as ad hoc social workers.

Much of the literature consulted confirmed that vocational awe—the term coined by librarian Fobazi Ettarh to describe the idea that the library’s mission is so deeply worthy as to be beyond critique or question—can result in an acceptance of abuse, violence, and the resulting trauma as the norm. Racial and sexual incidents are normalized as “things that everyone goes through on the job,” and the pandemic has also introduced the need for staff to enforce safety mandates for an often-uncooperative public. “If staff are constantly on the lookout for the next awful thing then they begin to expect awful things all the time, and hypervigilance sets in,” Comito and Zabriskie write. “This feeling of always being on guard makes interactions with patrons and other staff challenging and contributes to burnout.”

Secondary traumatic stress (STS), the trauma brought on by working with—and bearing witness to—community members experiencing trauma, is also common. The concept has been widely explored in the medical, psychiatric, and social work fields, but there is very little acknowledgment that library workers are dealing with similar challenges, and having many of the same kinds of reactions, including compassion fatigue and burnout. “Explicitly connecting the dots between library literature’s stated need for a trauma lens and the social work field’s acknowledgment of the risks of vicarious trauma is one of the most important things this study can accomplish,” the report states.

Library workers experiencing burnout are frequently encouraged to take advantage of professional help or an Employee Assistance Program (EAP); other broad solutions commonly posed include self-care, boundaries, and mindfulness, none of which are sufficient to address the seriousness of the problem, the report notes. (See also “Feeling the Burnout.”) Staff are often not given enough time to decompress after an incident, and are reluctant to use the library’s EAP lest that request go on their record—only 20 of the more than 400 respondents indicated that they had used available mental health resources.

CRITICAL SUPPORT

A lack of support at the leadership level during or after a traumatic event was a common criticism. “Although many of the incidents of trauma in the library were directly related to larger culture issues that stem from outside of the library (e.g., racism, sexism, substance abuse, etc.),” the report notes, “the trauma that was incurred by many respondents was often a result of how the situation was handled inside of the library.”

There is often distrust between frontline staff and leadership, according to feedback from focus group and forum participants; many report feeling that administrators are too far removed from public service roles, or never served them in the first place, and workers feel that those in leadership are unable to understand what frontline employees—who are expected to provide good customer service no matter how they are treated—deal with on a day-to-day basis. This was exacerbated by the pandemic, when staff were frequently expected to return once buildings reopened and leadership continued to work remotely. Human relations (HR) departments are also considered to be disengaged by many respondents; even unions are not always seen as helpful.

When incidents occurred, many focus group and forum participants felt they were often not believed by managers or administrators, or that incidents were downplayed or quickly written off. They reported being frustrated by poor communication, lack of empathy, and inconsistent application of policies and procedures. The majority of support after traumatic incidents occurred was offered by colleagues and supervisors; nearly 31 percent of survey respondents said that they felt “moderately supported” and close to a quarter felt “absolutely supported.”

Many said that they were told they were unauthorized to call emergency services for patrons in crisis. “We have had multiple patrons come in with weapons, everything from large sticks to guns and knives,” notes one respondent. “We try to call the police as little as possible so that everyone feels comfortable in using the library, but when this sort of thing happens we need to protect staff and other patrons. Frontline staff are having these very disturbing confrontations, and at the same time are getting pushback from the library administration about calling the police.”

|

PRACTICAL PROTOTYES Forum participants broke out for brainstorming sessions and created posters outlining simple solutions to a range of challenges |

When asked what would help to better mitigate workplace trauma, responses centered on creating a more supportive environment at work, maintaining adequate numbers of staff and security personnel, providing training and education for workers, and increasing the safety and security of the physical spaces. Many spoke to the need for more worker-centered policies and procedures. For example, incident reporting and follow-up processes need to be overhauled. Most incident reports are ineffective as a response, and often force the employee involved to reexperience the trauma as they try to summarize it. Staff are advised to keep reports fact-based, which can miss the nuances of perceived threat or emotional response.

Six focus groups, conducted virtually at the end of September 2021, reinforced how pervasively damaging the lack of support and communication were. “An overarching theme of the group was the feeling of helplessness and being alone,” the report states. “Many participants reported thinking that the event they experienced was only happening to them and feeling like they should be able to manage their feelings about it without external support.”

BRAINSTORMING FOR MITIGATION

“There is no one solution,” the report notes, “and addressing it will need to involve the work of a wide variety of stakeholders. We committed to developing a study based loosely on the principles of emancipatory research”—a method that prioritizes empowering the subjects of social inquiry—“and structured it using design thinking methods.”

Borrowing from the hackathon model used in civic data and coding communities, the design sprint in Brooklyn, NY, on March 9–11 brought together 35 library workers, managers, administrators, and volunteers from a range of library types and cities from New York to Anchorage.

After a day of discussion to define common problems and needs, participants divided into five groups to discuss systemic underlying issues that contribute to trauma in libraries as well as patterns and trends that lead to trauma events, the underlying structures that support those trends, and the mental models that reinforce those modes of thinking. After a few idea-generating exercises, the groups sat down to brainstorm practical ideas and create poster prototypes of how they might be put into action.

One team chose to create a peer support platform for staff experiencing trauma, identifying resources such as funding, trauma experts, and volunteers. Another proposed peer-driven, independently governed support networks, starting with local groups that would be supported by a national network. To provide support for workers and push back against the notion that they are “infallible superheroes” who don’t need extra help, a team suggested a library trauma accreditation, which would require libraries to offer localized support as well as directing workers to a larger support network.

Embedding library leadership in frontline roles and setting up partnerships pairing administrators with staff was suggested, with the goal of increasing communication and empathy. Another group proposed a multi-agency social services database that would allow library workers to search for services. A public view of the resource would be available for community use, with a backend edited, owned, maintained, and updated by library staff in collaboration with local agencies.

Tackling policy at the macro level, another team envisioned a strategic plan that injects trauma-informed principles into operations such as mission and vision statements, assessments, future planning, organization direction, objectives, mapping, initiatives, performance measures, and more.

The trauma study report recommended a national library worker help line, a set of standards for healthy library work environments built by a coalition of worker-led library organizations, policies and procedures written from the perspective of trauma-informed leadership, and a series of peer-led support groups made up of library workers.

These were only a few of the many ideas surfaced at the forum, but they were clear examples of interventions that can be implemented throughout the organization. “These issues will not be fixed quickly or patched easily,” Comito and Zabriskie write. “It will take a cultural sea change in the profession at every level to address these core issues of library work.”

Zabriskie, executive director of Onondaga County Public Libraries, NY, has been working to incorporate some of the project’s findings in his own system, including what may be the simplest: checking in. “Maybe you just make it an admin policy,” he tells LJ. “If an incident report comes back, then someone in leadership reaches back to the people who experienced this and checks on them. It’s a half hour phone call. It’s taking an hour to go by. It’s closing a branch for a day, or half a day, if something happens. I think that those things can go a really long way.”

You can read the full 2022 Urban Library Trauma Study report here.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!