LSU and Elsevier: A Tale of Two Contracts | Peer to Peer Review

In a May 2 statement, the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) announced that Louisiana State University (LSU) filed a lawsuit against academic publishing company Elsevier for breach of contract on February 27. According to the complaint, Elsevier cut off the LSU School of Veterinary Medicine’s (SVM) access to content that was legally licensed by LSU Libraries. For many reasons, especially Elsevier’s often contentious relationship with libraries over the decades, this will be one of the more interesting cases to watch unfold.

In a May 2 statement, the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) announced that Louisiana State University (LSU) filed a lawsuit against academic publishing company Elsevier for breach of contract on February 27. According to the complaint, Elsevier cut off the LSU School of Veterinary Medicine’s (SVM) access to content that was legally licensed by LSU Libraries. For many reasons, especially Elsevier’s often contentious relationship with libraries, this will be one of the more interesting cases to watch unfold.

In a May 2 statement, the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) announced that Louisiana State University (LSU) filed a lawsuit against academic publishing company Elsevier for breach of contract on February 27. According to the complaint, Elsevier cut off the LSU School of Veterinary Medicine’s (SVM) access to content that was legally licensed by LSU Libraries. For many reasons, especially Elsevier’s often contentious relationship with libraries, this will be one of the more interesting cases to watch unfold. The Facts

LSU Libraries has a large and expensive subscription to Elsevier content—at least $1.5 million dollars annually. The license covers LSU’s Baton Rouge campus and the associated Internet protocol (IP) ranges for access. LSU’s veterinary school, the focus of the current lawsuit, is located on the Baton Rouge campus. SVM had previously held its own license with Elsevier; when that license expired, vet school users continued to access Elsevier content, as licensed by the LSU Libraries agreement, since the LSU Library license states that it covers LSU’s entire Baton Rouge campus, including SVM’s IP range. In October 2016, Elsevier took action to block access to users at SVM. Shortly after, LSU wrote Elsevier and had that IP range reactivated. However—as yet unexplained in the lawsuit—Elsevier again blocked SVM’s access in January. This time, when LSU reached out to clarify the situation, Elsevier refused to respond to its requests to reactivate the vet school IP range. After Elsevier had shut off and then restored the licenses, LSU Libraries tried to license 19 additional veterinary titles from the publisher. Elsevier’s representative provided the requested quotes and LSU confirmed its acceptance of those terms, but later Elsevier refused to honor the agreement, or to license any of the agreed-upon titles to LSU.Location, location, location

Six weeks later, LSU filed a lawsuit for breach of contract in the 19th Judicial District Court, Parish of East Baton Rouge, LA. LSU attempted to serve Elsevier at its principle place of business: New York. Elsevier’s first move was not to accept service of process of the lawsuit at its New York headquarters because it is a Dutch company. Recently Elsevier claimed “[t]o help [LSU] avoid that time and expense [of filing internationally] we would be willing to accept service, but we wanted first to seek a commercial resolution.” You might be asking: Is that correct? Can Elsevier hide behind Dutch laws? Yes. However, as ARL Policy expert Krista Cox recently pointed out, Elsevier has certainly not refused to engage in the American legal system before. The company spends millions on lobbying the U.S. Congress, has sought judgments in our courts, and has testified directly on U.S. laws effecting scientific research, open access, and copyright. The company lobbied strongly against open access, reflecting its corporate interests and, interestingly enough, is a member of the Association of American Publishers. While awaiting proper legal international service is not illegal —Elsevier is a Dutch company—it certainly makes it harder for LSU to enforce its contract claim.The Hague

The Convention on Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil and Commercial Matters (“the Hague Service Convention”) is a multilateral treaty formulated in 1964 by the 10th Session of the Hague Conference of Private International Law to provide a simpler way to assure that defendants sued in foreign jurisdictions would receive actual and timely notice of suit, and facilitate proof of service abroad. The term “service of process” refers to a formal delivery of documents that is legally sufficient to charge the defendant with notice of a pending action. The primary text of the Hague Service Convention is the requirement that each state establish a central authority to receive requests for service of documents from other countries. Once this central authority receives the request in the proper form (some countries require perfect translation of the documents), it must serve the documents by a method prescribed by the internal law of the receiving state. The central authority then provides a certificate of service. This process, while organized and sound, creates a burden on the complaining party. LSU is going to have to jump through more than a few hoops, learn Dutch law, and make sure all its documentation and service conforms to the specific requirements of the Netherlands. It’s understandable that Elsevier wants this litigation to occur in its own “home court”—that is a natural strategy for any legal defense. I am not faulting the publisher for a defensive international law and jurisdiction strategy—but it’s delaying the inevitable on an issue that appears to be either: 1) a clear breach of contract or 2) an inability to respond in a timely fashion.Into the Breach

LSU is arguing that Elsevier has refused to abide by its valid, legal, and enforceable contract by blocking access to SVM. Despite the express provision in the contract that covers the IP ranges of the school, and despite the fact that Elsevier had shut off and turned access back on at least once before, Elsevier has continued to deny access. From the record, there was a valid offer and an acceptance of the terms of the offer. Most courts refer to that as the “meeting of the minds.” For Elsevier to renege on this contract is troubling. Reading the contract about the IP access, and looking at the accepted offer for the additional titles, there is a least a factual semblance of a breach of contractual obligations. In my opinion, this may be why Elsevier seeks the Netherlands jurisdiction: to buy time to regroup and build its defense. Maybe the offer was a mistake? Maybe the IP ranges weren’t looked at closely? Under the law it doesn’t matter. The Elsevier employees provided the offers, the contract, and the agreement, so they are bound by their actions. Moreover, on April 22, Elsevier proposed that LSU “add a minimum of $170,000 of additional 2017 subscriptions to their existing contract” and tacked on a $30,000 increase for another collection in order to restore access. Cox, of ARL, hits it right on the head:Once again, Elsevier is using its monopoly power—LSU can only get the titles owned by Elsevier from Elsevier itself—to try to extract more money out of LSU. Elsevier is hoping that by refusing to honor its contract, it will be able to pressure LSU to renegotiate its current contract and pay even more money…

Elsevier’s Side

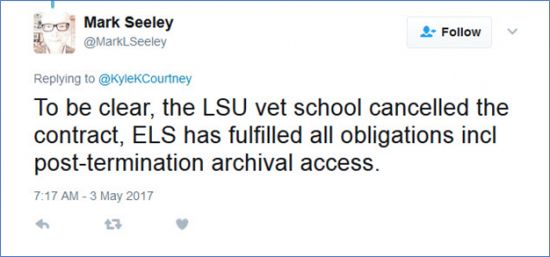

While I was tweeting about the case prior to writing this piece, I got a response from one of my peers at Elsevier, Mark Seeley, general counsel for Elsevier. Mark and I have met several times, and even have been on a few panels together. He stated: Mark has only tweeted about two dozen times before, so I took notice. And this may indicate some of the legal strategy that will be outlined by Elsevier, if the case goes to trial. I am not sure, according to Mark’s tweet, if there is a difference between his claim of “cancelling” a contract versus letting it “expire.” Despite these semantics, if the SVM did terminate/cancel/expire its contract (this will be the crux of some of the dispute, no doubt) then the case turns on the LSU Libraries’ contract that covers the vet school. Since SVM’s IP range is within the authorized list in the contract, there are no grounds for dispute there. However, one of the clauses states that there are 35,000 authorized users and then, below that, “Estimated number of relevant authorized users: 1,135.” I am not sure why that number differed between both parties’ contract terms, or what adding the users from SVM means to the obligations as defined in the contract. What is the difference between an authorized user and a “relevant” authorized user?

Mark has only tweeted about two dozen times before, so I took notice. And this may indicate some of the legal strategy that will be outlined by Elsevier, if the case goes to trial. I am not sure, according to Mark’s tweet, if there is a difference between his claim of “cancelling” a contract versus letting it “expire.” Despite these semantics, if the SVM did terminate/cancel/expire its contract (this will be the crux of some of the dispute, no doubt) then the case turns on the LSU Libraries’ contract that covers the vet school. Since SVM’s IP range is within the authorized list in the contract, there are no grounds for dispute there. However, one of the clauses states that there are 35,000 authorized users and then, below that, “Estimated number of relevant authorized users: 1,135.” I am not sure why that number differed between both parties’ contract terms, or what adding the users from SVM means to the obligations as defined in the contract. What is the difference between an authorized user and a “relevant” authorized user?  Arguably (and the letter from LSU to Elsevier explicitly takes this position), LSU asked for up to 35,000 users to be covered under the contract, which included all campuses in the IP range, “relevant” or not. In fact, as of 2015, enrollment at LSU was just over 31,000, including Law School and LSU Online students. Despite this dispute over increasing the number of relevant authorized users, though not the total number of authorized users, there was acknowledgement and specific performance by Elsevier in the past that, in my mind, nullifies any argument: When LSU asked Elsevier to turn access back on to SVM, Elsevier complied, and access was restored. Only later did they turn it back off. That indicates, at a minimum, that someone at Elsevier felt that SVM access was legitimate.

Arguably (and the letter from LSU to Elsevier explicitly takes this position), LSU asked for up to 35,000 users to be covered under the contract, which included all campuses in the IP range, “relevant” or not. In fact, as of 2015, enrollment at LSU was just over 31,000, including Law School and LSU Online students. Despite this dispute over increasing the number of relevant authorized users, though not the total number of authorized users, there was acknowledgement and specific performance by Elsevier in the past that, in my mind, nullifies any argument: When LSU asked Elsevier to turn access back on to SVM, Elsevier complied, and access was restored. Only later did they turn it back off. That indicates, at a minimum, that someone at Elsevier felt that SVM access was legitimate. What Next?

To date, Elsevier has denied SVM’s access to the licensed materials previously purchased, reneged on the new titles agreement, tried to settle the dispute by asking for further payment from LSU, and is using international law to temporarily avoid service of process in the U.S. courts. I think everyone in the academic industry and its related fields should watch this case closely. If it doesn’t settle, it will be fascinating to see the contractual arguments play out at trial, and maybe even on appeal. But allow me to stand on my podium for just a moment: what is this lawsuit really about? Well, as the LSU complain plainly states:“Elsevier is well aware that LSU, like other universities, is heavily reliant upon the various types of research and educational content for which Elsevier enjoys monopolistic market powers…Elsevier is unfairly abusing its leverage to coerce LSU into paying additional and unnecessary subscription fees for research and educational content…”Let us take a lesson from this moment to re-examine priorities for our campuses, libraries, and administrations—places where millions of dollars are being paid to outside parties to access the scholarship emerging from inside our campuses. Wouldn’t that money be better spent elsewhere? Let’s shift our dollars to internal causes: building repositories, passing open access policies, increasing access, and as my colleagues at MIT have noted, using the “values of open access, diversity, and social justice as a lens for framing collections decisions” and investing in “guideposts for navigating and favorably shaping the scholarly communications landscape.”

Kyle K. Courtney (@KyleKCourtney) is copyright advisor at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Add Comment :-

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

TECHNOLOGY

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing