Prison Tablets and Borges’s ‘Infinite Library’

This Prison Banned Books Week, we’re calling for public library catalogs to be made available on prison tablets.

|

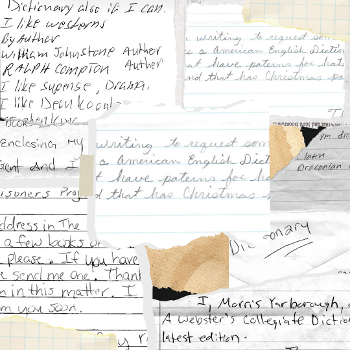

Requests for dictionaries received by Books to Prisoners Seattle |

Prisons across the country offer tablets to incarcerated people. Operated by prison telecom companies, these devices are widely appreciated by people in prison because they offer an unprecedented way to connect with loved ones outside. Many of these tablets also offer reading materials. The availability of electronic reading material could solve many common issues regarding access to information and literature in prison libraries: chronic underfunding, understaffing, censorship by non-library personnel, and little opportunity for library staff to challenge these bans. Theoretically, incarcerated people could have access thousands of books, which provide ample opportunities for self-development, intellectual growth, and productive leisure. In practice, prison tablets have become an engine of carceral censorship.

Catalogs on prison tablets resemble the library in Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “The Library of Babel.” This library is a panoptic, unending labyrinth of hexagonal rooms, each containing the basic necessities for one man’s survival with books cramming the remaining space. To someone unbothered by austere surroundings, this library may seem a retreat. However, this “universe” of books is a special kind of torture. Every volume in the library contains a meaningless combination of “twenty-five orthographic symbols,” which fill the pages with gibberish. One book contains “the letters M C V perversely repeated from the first line to the last.” The overabundance and ready access to these useless books paradoxically leaves the “librarians” wallowing in despair.

Borges’s story is, of course, fiction, but it bears more than a passing resemblance to the content offered on prison tablets. Most available books incarcerated people can read for free are taken from Project Gutenberg, an online repository of more than 70,000 public domain texts. The curated collections on these tablets are overwhelmingly uninteresting and unreadable. There is A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary For the Use of Students, published in 1894; The Euahlayi Tribe: A Study of Aboriginal Life in Australia, published in 1905; The Ruined Cities of Zululand, published in 1869; Yankee Girls in Zulu Land, published in 1888, which, according to WorldCat, is noteworthy because it is “An account of one woman’s experiences in Africa; particularly interesting because of the racist attitudes expressed throughout.”

Why do titles like these comprise the majority of the catalogs on prison tablets? One reason could be that the volume of public domain content available through Project Gutenberg allows tablet companies to proclaim that they provide “more than 30,000 free titles” for incarcerated people to read. This sounds impressive. When you realize that nearly every title is like those listed above, this proudly publicized number transforms from a perhaps small library collection—relative to the roughly two million people that are detained and incarcerated in the United States—to a stunning attempt at obfuscation. If a public or school library contained this content, it would be the shame of any community.

Before public outcry, prison telecom companies charged people to read books that are available at no cost to the public. And they have made millions in profits. While for-profit tablet companies indeed function by generating revenue, it is more puzzling why state and federal prison systems would want to offer outdated, irrelevant, and often biased content—especially when there already exists an alternative infrastructure for providing digital access to materials: public libraries.

For example, New York City’s Riker’s Island contracted with the telecom company APDS to provide detained persons with free access to content specifically created for the tablets by the Brooklyn Public Library. Videos included drawing lessons and astrology, and reading materials from the National Corrections Library were available at no cost. But when the company’s contract expired, NYC’s Department of Corrections did not renew and instead contracted with JPay, whose free reading materials are taken from Project Gutenberg. The company projected $9 million in revenue over five years from the use of tablets by people detained in New York.

This kind of profiteering—even when it comes to books—is not unique to New York. Departments of Correction in Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and many other states receive kickbacks from prison telecom companies through the sale of media—including books and other reading material, movies, and music—which people purchase because there are few other options. Prison libraries are overwhelmingly understaffed with meager budgets. They’re largely prohibited from accepting donations and hamstrung by prison censorship policies, which are hyperbolic about sexual content—think censoring New Yorker cartoons—and supposed threats to security, such as a map of Westeros, the land in George R. R. Martin’s Game of Thrones.

Digital libraries on preexisting prison tablets could be a solution to these issues—if they were allowed to be. The San Francisco Public Library has been able to work with its local jail for this exact solution. A customized digital collection, curated by librarians, is now available on tablets for people incarcerated in San Francisco jails. Operating from the understanding that people incarcerated in San Francisco are library patrons, the Library’s Jail and Reentry Services staff coordinated with other City departments, advocates, technology companies, library vendors, and the Sheriff’s Office to ensure that detained people have no-cost access to e-resources.

This access is made possible through hoopla, and includes books, audiobooks, movies, and television. The collection, driven by patron interests and curated in accordance with county Sheriff’s Department restrictions, includes thousands of materials on a wide range of topics and is heavily utilized by patrons inside.

Communities already pay for the digital books in our libraries, and incarcerated people are part of our communities. Those in jail or prison, who make less than a dollar per hour for their labor, should not have to pay for materials that the community can access. By collaborating with local library systems, prison telecom companies could stop the tortuous metaphor of Borges’s infinite library and offer a catalog of titles that incarcerated people will want read.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!