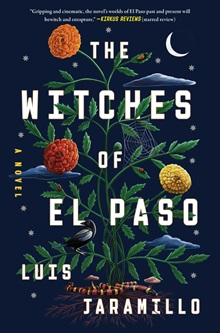

Author Luis Jaramillo on His Debut NovelThe Witches of El Paso

Luis Jaramillo is the author of the award-winning short story collection, The Doctor’s Wife. His writing has appeared inLitHub, BOMB Magazine, Los Angeles Review of Books, and other publications. He is an assistant professor of creative writing at The New School.

Luis Jaramillo is the author of the award-winning short story collection, The Doctor’s Wife. His writing has appeared inLitHub, BOMB Magazine, Los Angeles Review of Books, and other publications. He is an assistant professor of creative writing at The New School. He received an undergraduate degree from Stanford University and an MFA from The New School. His debut novel, The Witches of El Paso, is a richly imagined and empowering story of motherhood, magic, and legacy in which a lawyer and her elderly great-aunt use their supernatural gifts to find a lost child.

What was your inspiration for writing The Witches of El Paso?

I wanted to rework the stories of my grandmother and her sisters, very smart and lively women who were completely themselves—in high school, my great aunt Luz was famous for telling everyone she wanted to be a gangster’s moll, and she dressed the part, wearing short dresses and deep red lipstick. This was in contrast to my grandmother, who was referred to by her sisters as “The Saint.” My grandmother and her sisters lived in an El Paso that was rich with the bicultural life of the border, but their lives were constrained by their times and circumstances. If she had been born later, I think my grandmother would have been a politician. It was this idea of alternate lives that also made me want to tell this story. When I started, I was facing down middle age, in a panic about my own choices, wondering if “this” was it. While writing the book I kept asking the questions: Is it possible to change your life? And, what else is there in this world?

This novel takes place between 1943, colonial Mexico, and present day El Paso, Texas. What kind of research did you do to set the scene?

I interviewed family members, some of whom still live in El Paso. I also talked to lawyers and judges who work with immigrants in the region. I talked to writers and with professors at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). I also read a ton of books, like Ringside to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo, who I was also able to meet with. Two other helpful books were Rebellious Nuns: The Troubled History of a Mexican Convent, 1752-1863 and Brides of Christ: Conventual Life in Colonial Mexico, academic books that were full of details I needed. I also looked at old newspapers. Those from the World War II years were so key to helping me picture the world. I loved poring over the ads. I wanted to see all the things that the young Nena—one of the main characters—couldn’t have afforded to buy or experience, since novels are about all kinds of desire.

Family stories are a kind of legacy built on traditions and lore. Did you always set out to write about a family imbued with magic?

It wasn’t my intention to write about the supernatural. But in the writing, I found that using these elements allowed me to convey the uniqueness of the borderland with its complicated and rich mix of cultures, connecting the past with the present, the dead with the living. And then when I began to talk to my family members, it turned out that there were quite a few stories of the supernatural in family lore. Magic and time travel exist in the book because I want to show the timeless feeling of the border, and the way in which the family stories of people who have lived in one place for a long time start to sound like the telling of myths and legends.

The narrative largely revolves around complex, strong-willed women. Did you draw from your own family and your relationships with them to craft these characters? Was there a character that was the hardest or easiest to write for?

My dad, like Marta, the other main character of The Witches of El Paso, is a legal aid lawyer. When he was the head of El Paso Legal Aid, during my first-grade year, Border Patrol kept raiding restaurants and bars and then asking everyone who looked Mexican for their papers. Many of the people taken in by these raids were US citizens. In response to this, my dad filed a class action lawsuit and won. In another life I’m a lawyer like my dad, but in this one I’m a writer, so I made up Marta, someone who believes that logic rules all. In her, and in many of the other characters, there are echoes of the strong women in my life, women who have a fierce intelligence and a strong moral core. Nena, however, is not like anyone I actually know. She arrived with a voice and a story, and I quickly saw that it was my job to get down her words as accurately as I could. I never knew what was going to happen next with her.

How does the writing process differ between writing a short story collection and a novel? Was there anything that surprised you along the way?

Short stories are more like poems, meaning that images and language do a lot of the work. But in a novel, something really has to happen! My writing process involves a lot of false starts and a lot of revising, cutting sections, writing new parts, moving things around until they finally click into place. It’s not linear or fast, so it’s important that I work on it every day. To answer your second question, I was constantly surprised. Trust me when I say that I had no idea that I would end up writing about a coven of nuns in colonial Mexico.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading this book?

One of the great pleasures of reading is the ability to live a life other than our own. When I was a kid, I read so many books of fantasy and science fiction for exactly this reason. But as a writer, I also want to write about what’s actually happening in the world. In contrast to how it’s often portrayed, the border between the United States and Mexico is a magical place, and I wanted to capture the feel of what it’s like to live slipping between languages and nations, fluent in the vocabulary of each. It’s the mystery of our world that makes me want to write. The magical and natural life force that Marta and Nena gain access to, an essence I call La Vista in the novel, can sometimes be channeled but can never completely be controlled. If there was a lesson from the book that I learned—and that I have to relearn every day I write—is that creative work is a kind of magic, always there, available at any stage of your life.

One of the great pleasures of reading is the ability to live a life other than our own. When I was a kid, I read so many books of fantasy and science fiction for exactly this reason. But as a writer, I also want to write about what’s actually happening in the world. In contrast to how it’s often portrayed, the border between the United States and Mexico is a magical place, and I wanted to capture the feel of what it’s like to live slipping between languages and nations, fluent in the vocabulary of each. It’s the mystery of our world that makes me want to write. The magical and natural life force that Marta and Nena gain access to, an essence I call La Vista in the novel, can sometimes be channeled but can never completely be controlled. If there was a lesson from the book that I learned—and that I have to relearn every day I write—is that creative work is a kind of magic, always there, available at any stage of your life.

SPONSORED BY

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!