Bloomsbury Applied Visual Arts: Spotlight on Imagined Worlds

Discover Bloomsbury Applied Visual Arts which combines visual inspiration with practical advice on everything from idea generation and research techniques to portfolio development – making this the ultimate guide to a visual arts education.

Going beyond the real

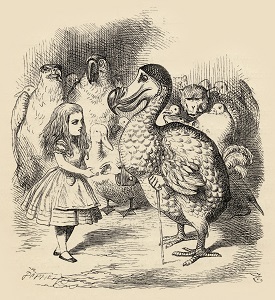

Fantasy and sci-fi, the twin genres of imagined worlds, are a two-way mirror. On the surface, they transport us through the looking-glass, beyond realism and into fictional landscapes that defy physics through dream logic and magic or near-future technologies that rewrite the laws of time and space. Yet these same fictional worlds often reflect and invert our present reality. It is no coincidence, for example, that Alice in Wonderland illustrator John Tenniel also produced caricatures for the satirical magazine Punch. If you look closely at his figure of Lewis Carroll’s dodo, you can see hints that it was based on the author himself. (Carroll, whose real name is Charles Dodgson, referred to himself as ‘Dodo’, on account of his stammer.) Tenniel mischievously gives his flightless bird a gentlemanly touch with two human hands and a cane.

Fantasy and sci-fi, the twin genres of imagined worlds, are a two-way mirror. On the surface, they transport us through the looking-glass, beyond realism and into fictional landscapes that defy physics through dream logic and magic or near-future technologies that rewrite the laws of time and space. Yet these same fictional worlds often reflect and invert our present reality. It is no coincidence, for example, that Alice in Wonderland illustrator John Tenniel also produced caricatures for the satirical magazine Punch. If you look closely at his figure of Lewis Carroll’s dodo, you can see hints that it was based on the author himself. (Carroll, whose real name is Charles Dodgson, referred to himself as ‘Dodo’, on account of his stammer.) Tenniel mischievously gives his flightless bird a gentlemanly touch with two human hands and a cane.

Imagined worlds

If world-buildi ng not only creates new realities but reshapes existing ones, imagined worlds then are a dialogue between fact and fiction, between known and speculative quantities. Genre is just another term for the shared history of artistic tradition, and Mark Wigan’s chapter on the rich, interrelated context of fantasy and sci-fi skilfully connects the dots between the Brothers Grimm and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In Star Wars, George Lucas’s intertextual, genre-melding space opera, knights, princesses, and intergalactic battles come together to create an enduring modern mythology for the big screen.

ng not only creates new realities but reshapes existing ones, imagined worlds then are a dialogue between fact and fiction, between known and speculative quantities. Genre is just another term for the shared history of artistic tradition, and Mark Wigan’s chapter on the rich, interrelated context of fantasy and sci-fi skilfully connects the dots between the Brothers Grimm and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In Star Wars, George Lucas’s intertextual, genre-melding space opera, knights, princesses, and intergalactic battles come together to create an enduring modern mythology for the big screen.

Fantasy means phantasia

Fantasy comes from the Greek phantasia meaning ‘power of the imagination’. Often in storytelling (as in art), magic serves as a metaphor for idea formulation and authorship. (For Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings and language-obsessed philologist, the word ‘spell’ is significant for its double meaning.) But where do good ideas come from? Wizards, formerly of Arthurian legend and latterly of computers, have always been guides, visionaries, and keepers of knowledge. Fittingly, Michael Salmond’s chapter on computer game design explores Kentucky Route Zero, a modern odyssey about a trucker’s final delivery, from its origins as ‘Sidequest’, an experimental text adventure, to award-winning, feature-length game. Here the production process is its own hero’s journey.

Fantasy comes from the Greek phantasia meaning ‘power of the imagination’. Often in storytelling (as in art), magic serves as a metaphor for idea formulation and authorship. (For Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings and language-obsessed philologist, the word ‘spell’ is significant for its double meaning.) But where do good ideas come from? Wizards, formerly of Arthurian legend and latterly of computers, have always been guides, visionaries, and keepers of knowledge. Fittingly, Michael Salmond’s chapter on computer game design explores Kentucky Route Zero, a modern odyssey about a trucker’s final delivery, from its origins as ‘Sidequest’, an experimental text adventure, to award-winning, feature-length game. Here the production process is its own hero’s journey.

Seeing is believing

‘We always see with m emory,’ says English painter, draftsman, printmaker, stage designer, and photographer David Hockney. ‘Each person’s memory is different: we can’t be looking at the same things.’ The same is true of our communities and the landscapes we inhabit. Folktales collect around places and objects as easily as gossip does celebrity. Landscape architects draw on local fame, myth and rumour as well as a historical record for The Fairytale of Burscough Bridge, ‘a working title at first – like an old Brothers Grimm story or a Tim Burton movie – [for] a place filled with tall tales of nine-toed boatmen, window peepers and Grumman Hellcats.’

emory,’ says English painter, draftsman, printmaker, stage designer, and photographer David Hockney. ‘Each person’s memory is different: we can’t be looking at the same things.’ The same is true of our communities and the landscapes we inhabit. Folktales collect around places and objects as easily as gossip does celebrity. Landscape architects draw on local fame, myth and rumour as well as a historical record for The Fairytale of Burscough Bridge, ‘a working title at first – like an old Brothers Grimm story or a Tim Burton movie – [for] a place filled with tall tales of nine-toed boatmen, window peepers and Grumman Hellcats.’

SPONSORED BY

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!