Building A Better ERMS

Librarians have struggled for nearly a decade with how best to handle electronic resources, as the information economy has shifted inexorably toward electronic materials. In the interim, experimentation and product development has confirmed that electronic resource management (ERM) is nothing short of chaotic.

The problem is that managing e-resources is a distinctly nonlinear and nonstandardized process. Harried librarians—shuffling mountains of paper and sticky notes and juggling byzantine email folder structures—expected ERM systems to address issues of workflow efficiency and, especially, interoperability with other systems. Yet what has materialized, amid a patchwork of standards, is less like a silver bullet and more like a round of buckshot. The ERM systems that have been developed have addressed some needs very well, including license management and administrative information storage. They’ve left other issues, such as interoperability, unresolved.

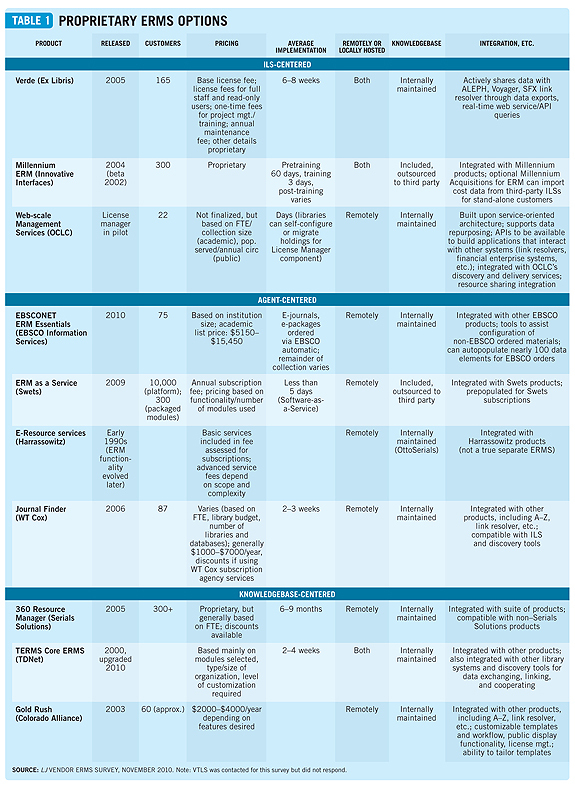

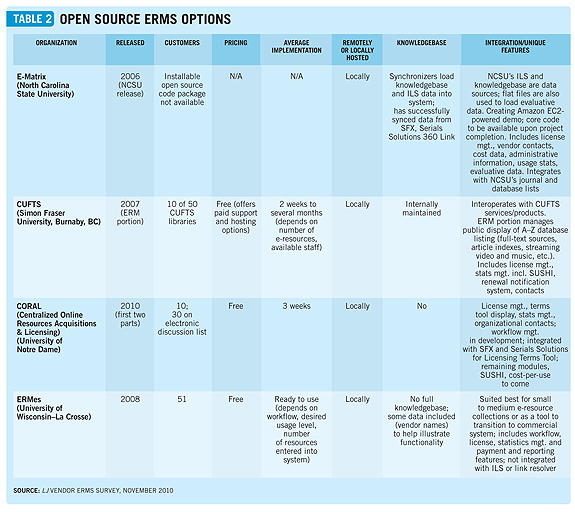

The complexity of ERM is often underestimated by those not deep in the trenches. To tap the reality in play, we conducted two surveys: one for librarians and one for commercial and open source ERM system vendors. A total of 66 academic librarians and more than ten vendors responded. We set out to find what librarians want—and need—in an ERMS, and they weren’t shy about telling us what was most important to them.

Librarians’ top six ERM priorities include workflow and communications management, license management, statistics management, administrative information storage, and acquisitions functionality. Another single priority, interoperability across systems, may well affect all the rest.

Librarians’ Top 6 ERM Priorities

- WORKFLOW MANAGEMENT: Support across e-resource life cycle, including resource tracking, reminders, status assignments, routing and redistribution of workflow, and communication, or notifications to stakeholders or patrons

- LICENSE MANAGEMENT: Manage license details, provide storage for agreements, and display license terms for internal and external users

- STATISTICS MANAGEMENT: Obtain, gather, and organize usage statistics. Auto-upload statistics using SUSHI standard. Provide historical statistics

- ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION STORAGE: Store and make accessible administrative information, such as usernames and passwords

- ACQUISITIONS FUNCTIONALITY: Provide acquisitions support for budget management, fund management, financial reporting, repository of cost data, and invoicing

- INTEROPERABILITY: Interoperate across systems, including the ILS, to support auto-feeds, data loads, and auto-updates

Librarians also named the following features as ERMS priorities, in order of popularity: subscription management, public display, vendor contact information, support for collection evaluation, consolidation of ERM information, package management, holdings management, reporting, and usability.

Workflow management

Over a third of librarians surveyed prioritized workflow or communications management, and they called it one of the biggest deficiencies (and disappointments) of ERMS functionality. One wrote, “Basic functionalities we had a decade ago with ILS systems are still not available in ERM systems.” Workflow has been addressed to a greater or lesser degree depending on the ERMS.

Librarians want to work with systems that can drive and support the acquisition of an e-resource by routing the resources from one step to another, and from one staff member to another. Given the nature of ERM, librarians also want a system of reminders to assist with tracking work stages, status changes, and renewals and to provide alerts about downtime. This all hinges on a notification system for staff members in the ERM process—one that allows for flexible email communication and sends alerts to external and internal users.

Workflow management has also been identified as a gap in the National Information Standards Organization (NISO) ERM Working Group Quarterly Report, which has prompted NISO’s ERM Data Standards and Best Practices Review team to identify and collect internal workflow documents for further analysis.

Adding complexity, often workflows that occur outside the ERMS itself need to be managed. Ex Libris product manager Nettie Lagace and VP of strategic partnerships Susan Stearns concurred, highlighting the potpourri of systems that libraries use to facilitate ERM. A library might use an ILS, link resolver, A–Z journal list, discovery interface, and an ERMS—all from different vendors—and tracking workflows across these systems is a definite challenge. Librarians complained that they often end up piecing together manual workflows to accommodate ERM tasks.

Librarians at the University of Notre Dame responded to this need when developing their local ERMS, CORAL (Centralized Online Resources Acquisition and Licensing), now available as open source. Notre Dame’s Ben Heet, technical resource administrator, and Robin Mallot, electronic resources technical consultant, described the CORAL system as a workflow management tool capable of notifying everyone who works with an e-resource. The developers made a deliberate decision to concentrate on workflows rather than designing a system that provides a complete picture of Notre Dame’s e-collection. They wrote scripts to query the separate knowledgebase for this kind of information at the point needed. This has freed developers to prioritize staff workflow problems, such as collections reviews and communication about resource status within the acquisitions life cycle.

Librarians noted a lack of flexibility in workflow components from commercial ERM systems. UCLA’s Angela Riggio, interim head of scholarly communication and licensing, and Bonnie Tijerina, digital collections services librarian, discussed the need for ERM systems to accommodate local workflows, rather than force local workflows to fit a template. On the flip side, librarians said that workflow support from other commercial systems is too general and not granular enough; librarians were forced to create workarounds—such as shadowing public notes to create a mechanism for staff processing notes—that often complicated workflows rather than streamlined them.

Consequently, developing workflow management remains a catch-22—functionality is either too specific to match local practice, or too general to support local workflows. Norm Medeiros, associate librarian and coordinator of bibliographic and digital services at Haverford College, PA, noted that using workflow management systems from business sectors might possibly fill this functionality gap.

The makers of commercial systems with a workflow focus, such as Verde, are only too aware of this quandary. Ex Libris’s Lagace and Stearns acknowledged customer concerns about hardwired workflows and noted that Ex Libris’s Alma, currently in development, will combine ILS and ERMS functionality and benefit from lessons learned from Verde. Ex Libris continues to prioritize workflow management with Alma, which will be built on a business process engine, will be rules-based to allow users to customize workflows locally, and will automate processes via locally assigned thresholds. Most important, Alma promises to unify the ILS and ERMS in a single system that will intersect with a single knowledgebase. Stearns and Lagace point to the value of unified systems, saying that separate or add-on ERM systems are “neither the right way to go [nor] the wave of the future.”

License management

While workflow needs work, license management is something of an ERMS success story. Overwhelmingly, survey respondents said that ERM systems help make license management more efficient, allowing them to categorize licenses, and link contracts. Librarians are linking amendments with parent agreements and thus are able to get a more complete picture of all documents signed over time.Respondents also noted the ability to push license terms to relevant constituencies. For example, librarians can populate the ERMS with specific terms of use for interlibrary loan (ILL) rights, and, depending on the system, librarians can push this information out through A–Z lists, the OPAC, or other mechanisms, which allows ILL staff across the library to make informed decisions.

Nonetheless, populating ERM systems with license terms can be a laborious manual process. Some emerging systems, such as those from subscription agents, are able to achieve automated population of general terms, but a manual element remains for library-specific license terms. In an attempt to address this, the ONIX for Publication Licenses (ONIX-PL) standard was created, “part of a family of XML formats for the communication of licensing terms under the generic name ONIX for Licensing Terms,” but it has yet to see widespread adoption.

The introduction of discovery layers also limits how librarians can inform users of license terms. One librarian noted that it is extremely helpful to be able to populate the ERMS with license terms and have those terms automatically appear in the OPAC. Unfortunately, however, a next-generation discovery layer is now the primary means of access to the catalog, not the OPAC, and those terms of use are not fed to the discovery layer from the ERMS. They are also not pushed out through the link resolver or other access mechanisms. ERM systems that are integrated with an ILS may or may not be able to push license terms to the A–Z list or to the link resolver, particularly if a library uses services from different vendors.

Statistics management

Statistics management is also problematic. Librarians’ most common complaint in this area is the failure of ERM systems to implement the Standardized Usage Statistics Harvesting Initiative (SUSHI) standard. Ex Libris’s Lagace mentioned that while new SUSHI configurations with vendors often require development on the part of the ERMS vendor and so may not be immediately available to customers upon request, more vendors are signing on. (A registry of vendors with SUSHI servers can be found on the NISO website, where other resources can provide assistance for librarians getting started with SUSHI. Open source codes for SUSHI clients are also available.)As SUSHI gains traction with vendors, perhaps the usage piece of the ERM puzzle will soon become a little bit easier. Oliver Pesch, chief strategist for e-resources at EBSCO Information Services, confirmed, “The SUSHI maintenance committee is working with COUNTER [the Counting Online Usage of NeTworked Electronic Resources initiative] to develop best practices for SUSHI implementation.”

That said, librarians’ complaints regarding statistics management highlight the standards problem, which extends across many librarians’ ERM concerns and is a key component of the interoperability problem explored in more detail below.

Administrative information storage

On the plus side, many librarians surveyed said that the storage and central accessibility of administrative information, such as usernames, passwords, and vendor contact information, worked well. One respondent noted that a central gathering place for this type of metadata has improved some components of e-resource workflow.Another noted that while the ERMS offers a one-stop shop for contacts, licenses, orders, or notes on past problems, the amount of work involved in manually gathering and entering all of this information has been formidable.

Acquisitions functionality

One need is certain: ERMS users want a centralized system that can run the gamut of acquisitions—including fund management, support for budget projections, reporting of expenditures by categories, and ready access to cost data at both the individual title and package levels—and the ability to track this kind of data over time.It is clear that the quest for easily finding out cost-per-use is like the quest for the Holy Grail for the librarians surveyed. Only a pure system with pure data, properly linked and related, is going to be able to achieve this functionality easily. Haverford College’s Medeiros noted that cost-per-use was initially viewed as potential low-hanging fruit that could quickly enhance the value of an ERMS. One must simply marry cost and use data and, voilà, cost-per-use.

In reality, cost data has proven to be quite nebulous. Without a widely adopted standard to support the exchange of cost data from the ILS to a library’s ERMS, librarians have often resorted to manual data entry. Librarians attempting to use cost data loaders said that these tools are clunky and require extensive data massaging. One librarian stated that he would rather work with the data in Excel.

With the CORE (Cost of Resource Exchange) recommended practice still receiving a cool reception from vendors, cost data exchange won’t be getting easier anytime soon. And there are additional issues with cost data, including obtaining itemized pricing and dealing with titles billed as a bundle or package.

Interoperability

In the end, however, it all boils down to interoperability. Though sixth on librarians’ top priorities, interoperability issues plague the ERM spectrum.In an ideal world, librarians would like to see systems talk to one another, to update metadata such as ISSNs and URLs automatically, support easy data transfer, and allow the export of data for repurposing in other applications. They want to see ERM systems interoperate with enterprisewide financial systems and vendor systems (subscription agents and book jobbers). Surveyed librarians complained repeatedly about lack of integration with the ILS, public-facing applications, knowledgebases, and vendor systems. This problem is evident across both commercial and locally developed systems.

The crux of the interoperability problem is a lack of standards, in development and in practice. Thanks to the cooperation of librarians, standards organizations, commercial vendors, subscription agents, and publishers, standards have indeed emerged. The aforementioned COUNTER Codes of Practice and SUSHI standard address usage statistic normalization and transfer. KBART (Knowledge Base and Related Tools) Working Group and the ONIX for Serials Exchanging address title and holdings lists. ONIX-PL, as mentioned, hopes to cover the exchange of license information and CORE exchange of cost information.

The NISO ERM Data Standards and Best Practices Review, meanwhile, has recently held informal focus group conversations, reviewed the ERMI data dictionary, worked on mapping data elements to appropriate standards, and studied results of recent surveys. The group hopes to report its recommendations in spring 2011.

For all this effort, however, the implementation of standards and best practices has been limited. For example, one survey participant noted that their ERMS only accommodated JR1 COUNTER reports—problematic when downloading usage statistics. Numerous librarians complained that they were still waiting for SUSHI.

The perceived “closed-box” nature of many systems doesn’t help. One librarian noted that their ILS vendor has taken a modular ERMS approach. This allows for ILS integration but very little interoperability with another vendor’s ERMS. Even within a company’s products, librarians griped about a lack of linked relationships in the underlying database for their ERMS.

The domino effect

Indeed, lack of system interoperability has created a domino effect of problems. For instance, even as many librarians praised ERM systems for finally consolidating ERM-related data, others emphasized that the data traditionally housed in the ILS environment—such as cost, fund, and vendor data—remains segregated from the ERMS without easy means for data transfer. One groused that his ERMS “does not talk to our ILS in any way, so a seamless transition of data from our ILS to our ERM is not possible.” Of course, poor data integration and missing links among data relationships also result in poor reporting by the system–another recurring criticism.Concerns about data ingestion quickly turn into concerns about data maintenance. Several librarians described the data within their ERM sytems as static and only as good as their ability to maintain it. The increase in workload has resulted in increased staffing needs for many libraries. One respondent said their library expects to adjust staff job descriptions, in order to distribute ERM work among more people.

Another effect is inconsistent public displays when the ERMS is not connected to public-facing applications. For instance, one respondent’s ERMS was integrated with the library catalog but not with LibGuides. Consequently, access points were inconsistent between the library’s catalog and web space, again resulting in the need for additional resources to maintain them.

Obviously, this is untenable in today’s economic climate. One librarian noted that if his library’s issues with ingesting cost data were not resolved, his library would cancel its ERM service. Another, discouraged by the slow pace of standards development and adoption, used to subscribe to the notion of “best of breed” to achieve maximum ERMS functionality—where you pick the best link resolver, the best ILS, and the best ERMS in the industry. This librarian no longer espouses this philosophy.

Thinking holistically

A different approach to ERM, embedded within a broader resource management framework, may eventually prove to be the more viable option. Most of the librarians interviewed mentioned that they were keeping an eye on developments from Kuali OLE (Open Library Environment) and OCLC as a possible alternative approach to some aspects of e-resource management. Kuali OLE and OCLC’s cloud-based ILS in development, Web-scale Management Services (WMS), are both built on a service-oriented architecture (SOA) that allows for the extension and interoperability of the system.Andrew Pace and Jon Blackburn from OCLC revealed that WMS will address the ERM problem as part of a bigger problem facing libraries: how to manage new resource types, access methods, and purchasing models presented to libraries today. Pace noted that OCLC has incorporated support for e-resources and licensed content within acquisitions workflows that will support the ordering of licensed e-products, via the WorldCat knowledgebase used for managing ERM and licensing. Essentially, WMS should provide an extensible, holistic approach to the original ILS problems that prompted the development of ERM systems in the first place.

To boldly go

Given the challenges for ERM systems, it is tempting to think we face a raging river with no bridge. But perhaps the ERM systems currently available are just that: a bridge between the traditional ILS and what lies ahead. No one single system currently available—commercial, open source, or homegrown—can possibly meet all needs.What librarians and vendors must do now is listen to those who deal every day with the complex task of acquiring and making accessible electronic resources. Instead of focusing on one system to rule them all, systems such as CORAL have stepped back and determined what can be built to deal with the real and immediate needs of their librarians.

In other ways, commercial systems are addressing those needs by tackling interoperability issues. Systems tied to the ILS to some extent allow for the exchange of cost data and other acquisitions functionality. Those tied to subscription agent information can eliminate much of the manual effort of populating an ERMS with data the agent already has. Others tied to knowledgebases allow for a single pool of data to feed a variety of access and management mechanisms.

Building a better and more responsive ERMS is an iterative process, and no emerging system is a silver bullet. Nonetheless, it is possible to work together toward a more integrated e-resource solution.

LJ Explores the Big Tools This is the second in a series of articles coming this spring devoted to new developments in major tools for libraries. The first, “Liverpool’s Discovery” (LJ 2/15/11, p. 24), looks at a new search tool in action. Upcoming, delve further into discovery tools with Judy Luther and Maureen Kelly as they explore them in depth in the March 15 issue, and read all about the many trends in ILS development in the April 1 issue of LJ.

ERMS Survey Methodology A survey of librarians was conducted in November 2010 via several library-related discussion lists, including SERIALST (Serials in Libraries Discussion Forum), ERIL-L (Electronic Resources in Libraries), and LIBLICENSE-L. A separate survey was sent to major ERMS vendors and developers. Both included follow-up interviews

| Author Information |

| Maria Collins is Associate Head of Acquisitions at North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and Jill E. Grogg is E-Resources Librarian at the University of Alabama Libraries, Tuscaloosa |

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing