Dartmouth Repatriates Samson Occom Papers to Mohegan Tribe

The papers of Samson Occom—Presbyterian minister, scholar, educator, and early funder of what would become Dartmouth College in Hanover, NH—have been restored to Occom’s Mohegan homeland in Connecticut from their previous location at Dartmouth’s Rauner Special Collections Library. On April 27, Dartmouth President Philip J. Hanlon led a delegation bringing the papers from New Hampshire to Connecticut in a repatriation ceremony.

|

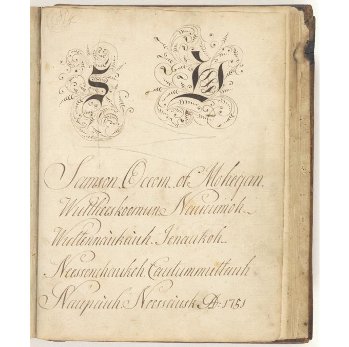

Samson Occom primer, Dickdook Leshon Gnebreet. : A Grammar of the Hebrew TongueCourtesy of Dartmouth College Library |

The papers of Samson Occom—Presbyterian minister, scholar, educator, and early funder of what would become Dartmouth College in Hanover, NH—have been restored to Occom’s Mohegan homeland in Connecticut from their previous location at Dartmouth’s Rauner Special Collections Library. The papers include journals, letters, traditional plant remedies, and some of the earliest known documents containing samples of written Mohegan language, among other material. On April 27, Dartmouth President Philip J. Hanlon led a delegation bringing the papers from New Hampshire to Connecticut in a repatriation ceremony.

Occom, a member of the Mohegan tribe born in 1723, was one of the earliest ordained Native American Christian ministers, among the first Native writers published in the colonies, and a spiritual leader and teacher in Mohegan. When his former instructor, congregational minister Eleazar Wheelock, established Moore’s Indian Charity School for Native students who wished to become missionaries, Occom spent years giving sermons across England, Scotland, and Wales, raising more than £12,000 (about $2.4 million today). Wheelock, however, used the money to build Dartmouth School for the sons of white New England families, rather than for the education of Native students. The two clashed publicly over the betrayal; Wheelock tried to slander his former collaborator, and Occom became an outspoken proponent of Indian rights.

Occom’s papers have been held in the college’s archives since the late 19th century, along with those of Wheelock and other figures from Dartmouth’s early history.

UNFINISHED BUSINESS

Although Dartmouth’s founding charter stated that it was created “for the education and instruction of Youth of the Indian Tribes in this Land...and also of English Youth and any others,” the college graduated only 20 Native students before 1970. In 1972, Dartmouth formally recommitted to its founding intent to recruit and educate Native American and Indigenous students, launching what is now its Department of Native American and Indigenous Studies.

A series of events were planned for 2022 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of this recommitment, including speakers, panel discussions, and exhibits. The Native American Visiting Committee (NAVC), a group of Dartmouth alumni established in the 1970s to advise the college president on Native issues, had been discussing how the college might honor the anniversary, and Sarah Harris, vice chair of the Mohegan Tribal Council and a Dartmouth alumna, proposed that it return the Occom papers to the Mohegan Cultural Preservation Center.

“The college has made a lot of progress in the years since that recommitment. However, there was this unfinished business with Samson Occom,” Harris told LJ. “Until we acknowledge the history of the school and Occom and really give life to that—to his story, his life, the college, and how we got to where we are—it’s difficult to say that there’s been real, meaningful change despite all of the progress that’s been made.”

NAVC agreed, and posed the suggestion to Hanlon, who in turn brought it to various other college stakeholders and the board of trustees.

At the same time, an advisory board of Indigenous leaders with experience in curation and collections, convened through an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant to Dartmouth’s library and Hood Museum of Art, was working on a joint project with the school’s Native American and Indigenous Arctic collections. One area of inquiry involved developing better protocols for Indigenous cultural objects in libraries and museums.

“It was in that context that we began to look at iconography on campus, looking at things that we have in our collections that maybe ought to be returned,” said N. Bruce Duthu, Samson Occom Professor of Native American Studies, a Dartmouth alumnus, and member of the United Houma Nation of Louisiana. It was a good opportunity to focus on “other areas where the college could reposition itself and reckon with issues of accountability and responsibility.”

The discussion about the papers moved surprisingly quickly, all agreed. During a call with Hanlon, Duthu, and several NAVC members less than a month after proposing the repatriation, Harris recalled, “We thought we were going to get an update on where the president was with this, what the college might want to do, what additional information they would like. The president instead announced to everyone that the college had agreed to return the Occom papers.”

“It was the smoothest process,” College Archivist and Records Manager Peter Carini added. “I thought we might have to have several meetings and defend our position, but we didn’t.”

“It helped tremendously that some of our peer institutions had already repatriated important items back to Mohegan,” noted Duthu; in March 2021, Cornell University Library repatriated the papers of Fidelia Fielding, one of the last fluent speakers of the Mohegan language. Since 1990, museums and other cultural institutions that receive federal funding have been subject to Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) mandates, which require them to return to return “cultural items”—human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony—to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated American Indian tribes, Alaska Native villages, and Native Hawaiian organizations.

“The return of those papers is like bringing the spirit of life back to his home ground, bringing it back to where it really belongs,” said Charlie Strickland, chair of the Mohegan Tribe Council of Elders. “The tribe will learn a lot more about what really took place through the Dartmouth papers as they get to see him and read them.”

DEFINING THE COLLECTION

Dean of Libraries Sue Mehrer, Carini, and Zachary Miller, cultural heritage and Indigenous knowledges fellow at the Hood Museum and Dartmouth Library and a member of the Chickasaw Nation, met with Mohegan representatives on their land to discuss the repatriation process. Both parties then gathered at the Dartmouth Library to determine what should be included. “They laid out some of the featured items in the collection,” said David Freeburg, archivist and librarian at the Mohegan Tribe Library and Archives. “We discussed some of the highlights, which really helped us because the plan was to exhibit them as soon as they returned.”

While the decision to repatriate the papers was arrived at easily, selecting the material was not as straightforward on Dartmouth’s end; it became clear that important items were spread out among several collections that would need to be broken up.

“Mohegan’s sense of what they wanted was not just the Occom papers [collection],” noted Carini. “They wanted anything that Occom had authored or written, because they feel that that material is imbued with his spirit. So that meant suspending my normal way of thinking, and suspending traditional Western archival principles, to basically cull out of the Wheelock papers letters and documents that had been sent to Wheelock by Occom.”

Items included a Hebrew primer with Occom’s notes in Greek, Latin, English, Hebrew, and what is believed to be the first instance that the Mohegan language was written down; autobiographical statements in which Occom responded to accusations questioning his background; a book of herbal remedies; sermons; correspondence; and journals that span from his time in England raising money to the founding of Brotherton, a Christian community Occom established in New York’s Oneida County.

“I was fortunate to be able to actually see the Occom paper displays that Peter and Sue and Zach had put together for us and for the Native American Visiting Committee,” Beth Regan, vice chair of the Mohegan Tribe Council of Elders, told LJ. “In that room, seeing his words, written, I could feel his spirit.”

The collection was digitized in 2011 as part of the Occom Circle project, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Neukom Institute for Computational Science, and the Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning; the digital versions and transcriptions will remain on Dartmouth’s website. This will not only ensure accessibility for scholars worldwide but will allow for continuity where the correspondence overlaps with other collections such as the Wheelock papers.

Both Dartmouth and the Mohegan Library and Archives use ArchivesSpace as their collection management systems, so the descriptive metadata associated with the collection was easily transferred. “I did warn their archivists that they were very colonial statements, and that they might want to edit them,” Carini said, “but it buys them some time to get to that over the next few years.”

A MOVING CEREMONY

The April ceremony was, by all accounts, a joyful and emotional occasion—and sobering, as longstanding harms to the Mohegan people were acknowledged.

A delegation from Dartmouth brought the papers to the Mohegan Church in Uncasville, CT. Dartmouth and tribal representatives spoke together privately about what the day’s proceedings meant to each of them, followed by a public ceremony of speeches and drumming with the group from Dartmouth, members of the Mohegan Tribal government, representatives of the Brothertown Indian Nation that Occom helped found, and other guests. Hanlon presented Mohegan Tribal Council chairman James Gessner Jr. and other tribal leaders with a box containing some of Samson Occom’s papers, along with a commemorative glass bowl etched with the date. Hanlon was given a hand-beaded purple and white leather wampum belt, signifying the bond between the Mohegan people and Dartmouth.

“We see this as a new beginning for the relationship between the tribe and the school,” said Harris. “I think it’s important that students, Indian and non-Indian alike, see those papers and view them in the context of his family, the tribe that remains today on the land that he fought to protect.”

Returning the papers to Mohegan land not only addresses a past wrong and offers tribal members direct access to Occom’s legacy—it brings a kinsman home. “Occom as a historical figure has this almost mythical status here at the tribe, but he’s also a family member,” said Freeburg. “When a tribal member is looking at these papers, they’re seeing his handwriting, they’re in the same room as something that he touched.”

Centering the scholarship around Occom on tribal land is critical as well. At the Mohegan Tribe Library and Archives, “our mission is to teach about Mohegan, and to be always learning about Mohegan,” said Freeburg. “Having these papers will bring people here to us, and to tribal members, for the story about Occom, so it makes Mohegan the center of the conversation. Up until now, if you were studying Occom, Dartmouth was really where you wanted to go to see these papers. But now, people want to come to Mohegan.”

“Knowing that we have [the archives] here is a great, spiritual thing,” said Strickland. “If you look at the papers, you’re going to see the past, you’re going to see the present, and our young ones are going to see the future. And that all takes place right in front of our own eyes, in our own hands.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!