Doing Fine(s)? | Fines & Fees

Fees and fines have traditionally been a fact of life for public libraries in America, even though a nonnegligible proportion of librarians and patrons have long considered fines at best an unpleasant hassle and at worst a serious barrier to access to resources for those unable to pay them. A number of libraries nationwide from High Plains Public Library in Colorado to Columbus, OH, to Ipswich, MA, have recently made news by eliminating charges for late returns. Others are creating fine-free cards for certain categories of patrons, such as California’s Peninsula Library System’s for kids and teens, or Toledo Lucas County Public Library’s for active duty military personnel and veterans. As many libraries continue to assess and overhaul their fine and fee structures, sponsored by Comprise Technologies, LJ surveyed a random selection of public librarians in January 2017 to learn about their libraries’ approaches to fines and fees. LJ received 454 responses.

Slightly over half of the libraries responding, approximately 60 percent, are classified as “small,” serving a population of 25,000 or less. Slightly over 20 percent were midsize, serving a population of 25,000 to 99,000; the remainder are classified as “large.” Responses came from locations across the United States and ranged from suburban branches to rural libraries to a slightly smaller percentage of urban library systems.

Overdue Fines Still in the Majority

A substantial majority of public libraries continue to depend on fines and fees for some portion of revenue, with 92 percent of survey respondents reporting fine collection for late returns. Eight-eight percent of small libraries collect overdue fees, and 98 percent of large libraries, serving populations over 100,000, do so. Not all libraries charge fines for every type of material—for example, some (five percent) do not charge fines for juvenile materials—but libraries almost universally charge late fees for DVDs.

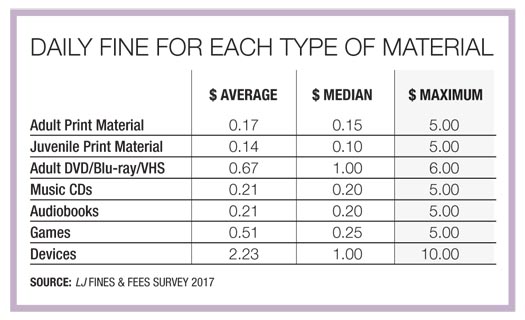

Librarians in the LJ survey estimated that about 14 percent of borrowed materials are returned late, with patrons in larger library systems slightly more likely to return items after their due date. The vast majority of overdue materials, 88 percent, are returned within one week of the due date. Only three percent of libraries reported an average late period exceeding three weeks. The daily fines for lateness are typically small, approximately 17¢, but can add up to a maximum of $5 to $10, or the cost of item replacement.

Monthly revenue from fines was roughly proportionate to the size of the system. Libraries serving populations under 25,000 reported an average of $449 in fines collected each month, libraries serving from 25,000 to 99,000 reported an average of $2,691, and libraries serving over 100,000 reported an average of $9,788. Based on responses to this survey and the number of libraries in the United States, LJ has projected the amount of money collected in monthly fines at approximately $11.8 million. This calculation is based on the total number of library systems in the United States and not the number of individual library buildings, making this a very conservative estimate.

Larger libraries are far more likely to accept credit or debit cards for fine payments than their smaller counterparts, with 88 percent of larger libraries accepting credit or debit cards, 65 percent of midsize, and 39 percent of smaller libraries. Nearly all responding libraries—99.5 percent—accept cash, 95.5 percent take checks.

Sixty-one percent of libraries also accept other ways to satisfy fines without monetary payment, although alternatives are less common in large systems, where just 37 percent offer such approaches. When they do, though, the results can be quite impressive: in recent amnesty programs, Chicago Public Library received at least 20,000 returned items, worth roughly $500,000; Los Angeles Public Library received 64,633 books, and 13,701 patrons had fines forgiven and accounts unblocked. Options include activities such as food drives, participation in programs in which patrons—usually children or teens—can “read down” their fines, donations representing a portion of the fine, or through amnesty periods. Multiple survey respondents referenced periodic fine amnesty periods as a powerful means of recovering overdue materials, which patrons may otherwise hang on to for fear of financial consequences. Indeed, the San Francisco Public Library recently held a six-week amnesty and recovered 699,563 overdue items, including 12,246 items that were more than 60 days past due.

WHERE THE MONEY GOES

The money collected is allocated to the general fund in about three-quarters of libraries. According to Jenny Paxson, readers’ advisory librarian at Webster Public Library, NY, “The money we get from fines helps us through the year. We use it as operating costs.” About 15 percent reported that funds go to materials, five percent that the money goes to programming, and six percent wrote in that fine money goes back to the city or county general fund. There have also been examples of libraries using fine revenue for other purposes—in 2016, for example, the Central Arkansas Library System donated a week’s worth of fine collections to help those affected by the extreme flooding in Louisiana earlier that summer.

Fines were originally instituted to dissuade patrons from bringing materials in late, depriving others of limited shared resources. It causes frustration for patrons and librarians alike, respondents noted, when they request items to find they are overdue and unavailable. There is a “responsibility factor,” says an Indiana library director. These are “community materials to be shared with all.”

Libraries will also take steps beyond fines for patrons who consistently hold on to their materials. Almost all libraries—97 percent—will suspend patron borrowing privileges when fines accumulate past a particular threshold, frequently around $10. Some refer patrons to a collection agency for outstanding fines long past due or over a certain amount. This is true of 67 percent of large libraries, 57 percent of midsize libraries, and 22 percent of small libraries. The typical threshold for such action is $42, and 54–90 days past due. Some libraries use a combination of dollar amount owed and number of days past due to determine whether they should take tougher action. A small percentage, 12 percent, have taken legal action to recoup overdue fines.

One factor leading to a decline in fine revenue for some libraries is the increasing prevalence of digital materials, which automatically “return” to the library at the end of the borrowing period. Nearly a third of responding libraries stated that digital materials have reduced their fine collections.

Fine Collection Stress

The majority of libraries (90 percent) have circulation staff communicate with patrons about fines, with fewer using email (67 percent), snail mail (55 percent), or phone calls (40 percent). In some libraries, patrons receive notification via text message, on their checkout slip, or through their online account. For many library staff members, the process of collecting and enforcing fines can prove stressful. The vast majority of libraries train their staff in how to handle it, particularly in libraries serving over 100,000, where 98 percent of staff receive training, although 88 percent of staff in midsize libraries and 79 percent in smaller libraries receive training as well.

Fine collection may also present a barrier to community goodwill toward the library. Said one staffer, “It’s not worth the severed relationships when responsible customers have a one-time occurrence, when families incur huge fines because of a vacation, or when the word of mouth messaging spreads because of any of these situations. Libraries have enough to combat, this is a matter of hospitality and being supportive of our customer needs.” Staff also feel concern about a negative effect on patrons’ use of their libraries. Says Monica Baughman, deputy director of Worthington Libraries, OH, fines can “impact those who can least afford it.” Bearing out Baughman’s point, when San José Public Library lowered fines and instituted a program for working down the amount owed through volunteering, nearly 100,000 residents had their library access restored. (For more, see “Jill Bourne: LJ’s 2017 Librarian of the Year,” LJ 1/17, p. 28.)

The time spent collecting these fees can use up hundreds of dollars in staff time from library budgets. Some libraries have found that the effort expended to enforce fines is not worth the small amount charged per day. Not surprisingly, about a third of librarians contemplate doing away with the practice entirely.

However, with budgets tight, many libraries are concerned about losing that source of revenue. Hollis Helmeci, director, Rusk County Community Library, WI, writes, “We would have to eliminate staff if we cut fines.” In particular, some referenced resistance to such a cutback from administrators, trustees, and local government. Others emphasized a belief that fines facilitate the timely return of library materials and patron accountability, with Mary Geragotelis, director, Scotland Public Library, CT, writing that “we believe that patrons will ignore due dates completely if there is no penalty imposed for late items.”

Some librarians compromise by waiving patron fines for those who cannot pay or restructuring the fines to pose less of a burden. As Cheryl Napsha, former director of the South Fayette Township Library, PA, writes, one deterrent to removing fines entirely is “board/local government expectation that fines are part of library service. It’s easier to waive fines than to deal with the board. While our system blocks people who owe $10 or more, we just override that or reduce fines to keep it below $10.”

Life Without Fines

Of those libraries that do not impose overdue fines, 45 percent had done so in the past. Most eliminated fines more than two years prior to the survey. The majority were unsure as to whether this change had impacted their circulation and instead focused on improving customer relations. Napsha observes, “Fines and fees should not be part of a library’s revenue stream,” as they have become “a barrier to service” and to a “cordial, positive atmosphere.”

Lisa Richland, director, Floyd Memorial Library, Greenport, NY, which has done away with fines but does restrict the borrowing privileges of those who have overdue nonrenewable items, reports, “folks who are dilatory about returns have not changed their habits, but the interaction at the circulation desk is much less fraught. My staff is not put in the position of punishing those who return items late, and we have a donation box for people who still have a need to pay a fine.”

Even without fines, the majority of library materials do make their way back to the library eventually. Not only does this reduce staff stress levels, Richland explains, but it also helps the library maintain a “good name” in the community. “You never know what burdens people have, so we try not to judge or act in a hectoring manner.”

Contrary to concerns that fines are the key to patron accountability, Kathy Dulac of the Milton Public Library, VT, reports that after doing away with fines, more people returned books on time, and others felt more welcome in the library space. She explains, “We also found some patrons that had not been in because of fines were again coming to use the library.” While some patrons take advantage and keep books out, she explains that “we have the best results getting books back by keeping on top of overdue notices.”

To offset the lost revenue from eliminating overdue fines, a small majority of fine-free institutions have started to collect voluntary donations at the circulation desk [see “Can Your Library Go Fine-Free?,” below]. Others simply adjust their operating budget, as the amount collected through fines represented a minimal percentage of the overall budget.

The Increasing Use of Fees

A majority of the responding public libraries—86 percent—also collect fees for library services. Based on survey responses and the number of library systems in the country, LJ projected the amount of fees collected by U.S. public libraries each month as $6.5 million.

Most of those fees are for in-library copying and printing, with some also charging to replace lost or damaged library cards or damaged materials or to grant access for nonresident users. Of those charging for nonresident use, six percent reported determining the fee based on tax rates. Smaller libraries in particular charge fees for faxing and scanning, while larger libraries are more likely to charge for services such as interlibrary loan (ILL) or debt collection processing. For ILL or document delivery, about eight percent will assess the charge from the lending institution, while eight percent will charge the cost of return shipping. Over a third of libraries, particularly larger systems, also charge for the rental of meeting rooms or event spaces. The revenue collected from such fees enables libraries to provide services they might not otherwise be able to offer, for instance, Wi-Fi kits or 3-D printing.

One in five libraries also charges admission fees for programs or events. Common events include classes such as art or yoga, field trips, or author talks. Other examples provided by survey respondents include driver safety courses, genealogy seminars, “paint n’ sip” gatherings, and concerts. Libraries also host free events at which participants pay for materials, like craft classes, or organize fundraisers for which attendees pay a fee or a donation.

Some libraries take a flexible approach to how they charge for common services like printing and copying. Steven Harsin, director, Grand Marais Public Library, MN, describes operating “on an honor system, so we don’t know for certain whether patrons pay nor not.... Undoubtedly, some do not pay. On the other hand, there are patrons who print a couple of pages and drop $5 in the bucket.” The library also will negotiate lower rates for large printing jobs and allows patrons to bring one copy of a tax form to be duplicated for free during tax season. Overall, library staff report efforts to adjust their fee structures in a manner that facilitates the best possible services for patrons and emphasize that these charges are never instituted to make a profit.

Many libraries are still testing what works best for their community when it comes to fee programs. Lisa Eck, Roseville Public Library, CA, notes that her library used to charge for held materials not picked up and for the processing of lost items, damages, and ILLs. However, she writes, “we have dropped [those charges] because we found that they didn’t warrant the staff time, and they caused negative experiences with our customers.”

As is the case with overdue fines, for many libraries the money collected in fees helps to support a tight institutional budget. Explains a public services librarian in Wisconsin, “As our city continues to slash our budget, our meeting room fees (collected for private events usually held on the weekends) are helping to plug the holes.”

The results of the LJ survey provide a picture of the ways in which libraries nationwide assess and adjust their approaches to fines and fees in order best to serve their patrons. The clearest trend from these results is that libraries benefit from open-mindedness about these revenue sources and a willingness to move away from entrenched traditional methods. There is a cost, in staff time and effort particularly, to collecting fines and fees from patrons, and libraries must balance this by collecting in a way that makes sense for the individual library and community.

Can Your Library Go Fine-Free?

By Steven A. Gillis

Many library administrators feel that fines are a barrier to access (especially for low-income families), cost the library significant staff time, are antithetical to our mission and principles, set up an adversarial relationship, or prevent implementation of services such as autorenewal. Nonetheless, they may fear that eliminating fines is impossible owing to funding issues. That is not necessarily the case. In the face of declining budgets and increasing costs, how can a library justify removing a revenue stream? A close look at the business situation may allow for a step-by-step transition, especially as fines collected often represent less than one percent of total budgets. A small trial period may be the answer.

At the Orange Beach Public Library (OBPL), we instituted such a trial, with rigid data tracking. Even if the project were a complete disaster, the board considered six months a minimal risk. We compared collected data to a baseline averaged from our 2010–12 calendar years. Our primary data points were circulation and average time materials stayed off the shelf, but we also examined the cost of the initiative and took note of staff and patron opinions, including patron email surveys in 2013 and 2016 that collected over 2,000 responses. Most important for concerns over revenue reduction, we tracked data on fines plus donations collected in our baseline vs. our donations collected during the experiment.

Altruism vs. punishment

Initially, we used a “waive-and-request” method. Fines were unchanged in our library automation software, but we would inform patrons that we were waiving the charges and asked if they would like to make a donation. While some chose not to donate, others donated at least the fine amount, often rounding up to the nearest dollar rather than receiving change. This method served to advertise our fine-free status, helped tracking, and sparked many questions from patrons. It also changed the tone of the interaction from punitive to altruistic, which was more pleasant for everyone.

Data from the first six months showed an overall decrease of only $265 compared to our baseline of combined fines and donations after excluding large or organizational gifts. This amounted to a 12 percent loss for these combined revenue streams. Almost 88 percent of fine income was recovered in donations through “waive-and-request” or from increased general giving. Comparing fines actually waived in our ILS reports vs. donations collected showed that 49.9 percent of the fine values were recovered through “waive-and-request.” After six months, the experiment was considered successful enough to go forward. We continued tracking and did see some ongoing falloff. After nine months, our recovery dropped to only 41.8 percent. It may be a good idea to anticipate and plan for a drop once the novelty wears off.

Revenue from the combined streams for the same six-month season of the original experiment did decline slightly. Because our library is located at the beach, our usage can be very seasonal, so we made sure to compare the same six months for each year and included our highest fine-generating months in the snapshot. Losses for fine incomes compared with donations fluctuated from 15 percent to 32 percent for 2014–16 ($330–$713). Even the highest percentage loss in 2016 was actually an increase in small donations by more than 25 percent over 2012, with this increase making up for 68 percent of our previous fine incomes. Our “waive-and-request” period ended in 2015, and in April 2015, we removed all fines at the direction of the library board.

Our test indicates that increases in donations may help mitigate the losses in fine income with the proper framing. Instead of planning for a one to two percent loss in total income, you may experience a surge in donations and goodwill. There is no real way to know if this will occur without trying a test period.

Goodwill grows support

At OBPL we were able to leverage increased goodwill with our city council. While there are many reasons for the raises in funding for our library, the goodwill of the community and the change in the overall environment from removing fines is a significant factor.

In the first year of the project, our municipal funding increased by nine percent over funding in 2012. Over the next three years, our municipal support has increased by nearly 30 percent. We currently anticipate a continuing budget of almost $140,000 greater than our 2012 funding. With this increased revenue and support from our city, we also anticipate remaining fine free.

Steven A. Gillis is Director, Orange Beach Public Library, AL

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing