Growing a Library: National Tropical Botanical Garden | Archives Deep Dive

While there are many botanical gardens across the United States, only one has the distinction of being a tropical botanical garden chartered by the U.S. Congress: the National Tropical Botanical Garden, located in Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi.

|

Courtesy of National Tropical Botanical Garden |

While there are many botanical gardens across the United States, only one has the distinction of being a tropical botanical garden chartered by the U.S. Congress: the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG), located in Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi.

Botanists, local and national organizations, and concerned individuals lobbied Congress to charter the Pacific Tropical Botanical Garden (PTBG)—its initial name—in 1964. The charter outlined the purpose of the PTBG to be “an educational and scientific center in the form of a tropical botanical garden or gardens” to encourage and conduct the study of tropical plants for basic and applied science; disseminate botanical knowledge; collect and preserve tropical flora; and contribute to the education and recreation of the people of the United States.

However, the PTBG didn’t break ground for several years after that. Thanks to a donation by Robert Allerton, one of the charter members of the newly founded garden, the PTBG was able to purchase its first parcel of land: 171 acres in the Lāwaʻi Valley on Kauaʻi’s South Shore. Over the following years, botanists and other plant enthusiasts donated the funds and land to expand its holdings.

The PTBG began developing its library collection thanks to Maria Stewart, the wife of its first director, William S. Stewart. She started the library with a small collection of botanical and horticultural books, explained NTBG Senior Research Botanist David Lorence.

The organization expanded beyond its Hawaiian borders in 1984 with Catherine “Kay” Hauberg Sweeney’s donation of her property in Coconut Grove, FL, previously owned by the botanist and explorer Dr. David Fairchild. In 1988, the U.S. Congress amended the charter to rename the organization the National Tropical Botanical Garden.

As the acreage and plant holdings expanded, the library and its archives continued to grow over the decades, with additional acquisitions from botanists and other enthusiasts. One of the largest was the 1998 acquisition of the Loy McCandless Marks Botanical Library. McCandless had been part of the original lobbying efforts to create the botanical garden; as president of the Garden Club of Honolulu, she helped gather support from other wealthy denizens of Hawaiʻi and the continental United States, including the Garden Club of America in Washington, DC.

McCandless’s library is “the finest personal collection in the United States of rare botanical illustrated books,” according to Lorence. Focusing largely on 18th- and 19th-century works, it contains over 5,000 titles about the tropics, subtropical botany, and horticulture, housed in the rare book room in the NTBG’s Kauaʻi headquarters.

Additional donations to the library include book collections from retired botanists, including Harvard professor Dr. P. B. (Barry) Tomlinson, who specialized in plant anatomy, mangroves, and monocots; and Dr. Daniel Palmer, who donated an extensive collection of books on ferns and fern allies. The NTBG has grown to five locations across the country—Allerton Garden in Kauaʻi; Kahanu Garden in Maui; Limahuli Garden & Preserve in Kauaʻi; McBryde Garden in Kauaʻi; and the Kampong in Miami, FL—on more than 2,000 acres of land, featuring an herbarium, library and rare book room, gardens, and research centers.

The NTBG website notes that “Western models of science and discovery in the natural world have benefited immeasurably—and too often—at the expense of Indigenous peoples. Indigenous cultures have, over millennia, developed their own systems, knowledge, and stewardship that have and continue to inform NTBG as it seeks to understand, explain, and preserve the natural world.”

The NTBG continues to examine “the relationships between people and plants as exemplified by Hawaiian cultural practices,” according to its website. “This appreciation of Indigenous knowledge complements our decades of plant exploration, discovery, taxonomy, systematics, and horticulture as components of biocultural conservation.” It is working to “document the way native Hawaiians viewed and cared for the natural world in which they lived” under the Indigenous Communities Mapping Initiative, which started in 2020 and has over 2,500 participants.

“By preserving books and periodicals that contain and have recorded Indigenous knowledge over the years, including Indigenous names and uses of plants, as well as their accurate scientific names and current conservation status, our library preserves and makes available this knowledge for those who want to learn more about it,” Lorence explained.

A GARDEN OF BOOKS AND EPHEMERA

|

Indigenous flowers of the Hawaiian Islands; 44 plates painted in watercolorsCourtesy of National Tropical Botanical Garden |

The library collection contains an estimated 20,000 books, including relevant botany journals such as Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, published by the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, UK; slide collections; and other ephemera with a focus on botany in the Pacific Island archipelagos and beyond.

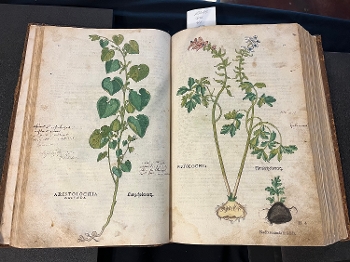

One of the oldest items is the Italian Herbolario volgare nelquale le virtu delle herbe , published in 1522—a translation of the Herbarius, “an anonymous compilation from classical, Arabic and medieval sources first published in Mainz in 1484,” according to the NTBG catalog. The book contains woodcuts that were used as reference for physicians “to try to identify plants so that they wouldn’t poison their patients,” said Lorence.

Other notable books include Banks’ Florilegium, with over 700 copperplate engravings of plants found on Captain James Cook’s first voyage around the world from 1768–71. Sir Joseph Banks, an English naturalist and botanist, collected and classified plants on the voyage, along with other members of the crew. The engravings were done from drawings of specimens by Scottish botanical illustrator Sydney Parkinson, who died of disease on the voyage in 1771.

Banks also would not see the completion of his masterpiece. He died in 1784, leaving the plates to the British Museum. Between 1980 and 1990, the British Museum and Alecto Historical Editions created 100 full-color complete editions of the Florilegium, of which the NTBG acquired four.

The library holds an early version of Herbarium Amboinense (1750) in both Dutch and Latin, by German-born naturalist Georg Eberhard Rumpf (1627–1702). He wrote the book, focusing on the plants on the island of Amboina—in modern-day Indonesia—but also died before he saw it published. The Herbarium was translated into English by the late Prof. E.M. Beekman, of the University of Massachusetts, using the NTBG’s version; the library contains a copy of his translation as well.

The collection has more than 6,000 35mm slides, in both black and white and color, that NTBG staff have taken, documenting the growth of the garden and the plants, and research trips throughout the Pacific. The library is working to digitize and label them, as many have no documentation attached.

One of the more unusual items in the collection is William Hillebrand’s personal album of fern specimens. Hillebrand (1821–86) was a German physician who is credited with being the earliest Westerner to document flora on Hawai‘i. The leatherbound album uses a photo album format where, instead of photographs, he inserted cards holding small fern specimens.

According to Michael Hayward and Martin Rickard, authors of Fern Albums and Related Material (2019), fern mountings like this were very popular in New Zealand, often including bits of moss and other leaves from the area where the fern grew. These little fern albums were “like souvenirs or collectors’ items at the time,” said Lorence.

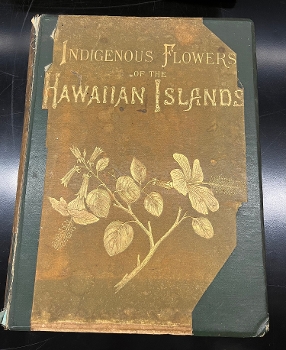

One of Lorence’s favorite items is a copy of Indigenous Flowers of the Hawaiian Islands by Isabella Sinclair (1852–1900), published in1885. Sinclair was a Scottish-born botanist who ended up in Hawai‘i, and observed and painted watercolors of the flowers of the islands. She sent a selection of them to the director of London’s Kew Gardens, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, who encouraged her to publish her work. “It has some beautiful color drawings of the native plants of the Hawaiian Islands,” Lorence said. “We have a copy that was signed by King Kalākaua [1836–91].”

RESEARCH, ART, AND CONSERVATION

Both artists and scientists have made use of the collections. Jon Letman, in charge of editorial and production at NTBG, noted that botanical artists visit annually for the Botanical Illustration Workshop, exploring the Kauaʻi-based Sam and Mary Cooke Rare Book Room that highlights the botanical art collection. NTBG has facilitated several botanical illustration workshops at its various locations, and even displays art from the NTBG Florilegium Society, a group of botanical illustrators and artists. Tattoo artists browse the collection to get ideas for tattoo designs.

Staff members studying at the University of Hawai‘i have made use of the collection as well. Kassie Jensen, NTBG intern, wrote her master’s thesis on Hawaiian mosses, and Kevin Houck, plant records manager, researched his MSLIS thesis at the NTBG library. The NTBG hosts a fall internship program for undergraduate and graduate students from Hawai‘i to Puerto Rico and even England; they use the library for projects that they present at the end of the internships. Student groups from Kaua‘i Community College and the study-abroad program at Campbell University, NC, frequently tour the Botanical Research Center, including the library.

NTBG published its first book, Dr. Harold St. John’s List and Summary of Flowering Plants of the Hawaiian Islands, in 1973, and republished Joseph Rock’s 1913 The Indigenous Trees of the Hawaiian Islands in 1974. Lorence served as the editor of Allertonia, a journal of papers published by the NTBG, which is currently on hiatus.

Recently, NTBG partnered with the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History to publish the Flora of the Marquesas Islands Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, based on three decades of fieldwork in the region.

In addition to the library and rare book collection, NTBG has a herbarium, founded in the 1970s, composed of about 90,000 dried and pressed plants from both the garden and, beginning in the 1980s, specimens from other Pacific locations, such as the Marquesas Islands.

While the herbarium is small compared to the Smithsonian Institution or the Field Museum in Chicago, said Lorence, the research facility was built to hold the library, herbarium, and research offices on the same campus. “I can just walk out of my office 50 feet and go into the herbarium collections and examine any specimens I want to study,” he added.

With the increasing impact of climate change, devastating forest fires, habitat loss, and other global challenges, the work of the NTBG continues to play a critical role in collecting and researching the plant life of tropical regions and educating people about it. One of the original impetuses of the NTBG’s founding was Joseph Rock’s research. He published his Indigenous Trees of Hawaiian Islands in 1913; after studying plants in China for nearly 30 years, he returned to Hawai’i in the 1950s and found that many of the species he had documented in the 1900s and 1910s were disappearing. Seventy years later, the losses continue to mount.

Those interested in visiting the collections and rare books must make an appointment; Lorence suggested they email him at dlorence@ntbg.org, with the caveat that the rare books library offers limited access.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy: