Growing Room: St. Louis Public Library's Grand Central Renovation | Library by Design

There was never a doubt that the St. Louis Central Library building would remain a library and be restored, St. Louis Public Library (SLPL) executive director Waller McGuire tells LJ. Patrons love to tell McGuire of their first experience at the library when they were children and a parent or grandparent led them up the granite steps and into the marbled Grand Hall. “The St. Louis community and beyond has a real attachment to the Central Library building,” McGuire says. “The St. Louis community loves Central.”

However, what was in doubt was the footprint. The original plan called for a proposed expansion outside the building’s original granite walls. But a local architectural firm took the risk of trying to convince library leaders that was the wrong way to go.

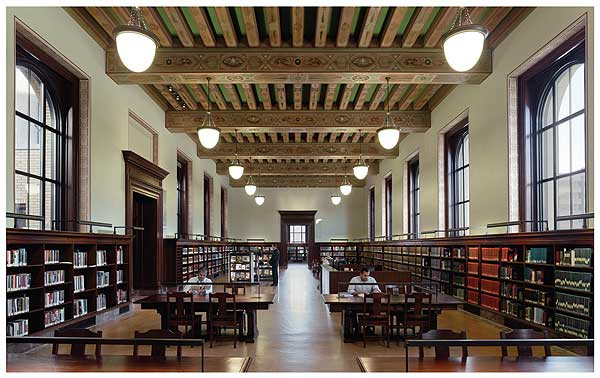

GRAND & GRANDER SLPL’s Great Hall maintained its grandeur even as the rest of the library gained flexibility.

Photo ©Timothy Hursley

Two years and $55 million later, the risk appears to have paid off. The restored and renovated 101-year-old Central Library reopened on December 9, 2012. Together, architects and librarians had almost doubled the square footage open to the public without expanding the original walls an inch.

Inside, SLPL patrons are discovering new spaces that serve dedicated readers, serious researchers, teens and children, and people exploring technology or recording their own music.

Underneath marble and wood floors and inside 19th-century ventilation, shafts run the power cords and fiber-optic cables to blend with 21st-century technology services, including expanded Wi-Fi and newly added self-checkout. The past, the present, and the future live side by side on the second floor in the Great Hall, with the original oak reading desks retrofitted to provide power for library users and brighter and energy-efficient lights glowing in century-old bronze fixtures.

In the middle of the first floor, the Center for the Reader offers 5,700 square feet of space dedicated to popular reading. Quotes from books emboss the recessed ceiling, and the furniture invites people to curl up or to gather for impromptu discussions. “We wanted to create that sort of rich, beautiful, convenient environment dedicated to the story,” says McGuire. “We placed that in the heart of the building.”

St. Louis Central Library by the Numbers

Opened January 6, 1912

Original cost $1.5 million

Andrew Carnegie gift $1 million

Original architect Cass Gilbert

Restoration architects Cannon Design of St. Louis; George Z. Nikolajevich, architect; Lynn S. Grossman and Matthew Huff, project architects; and Richard Bacino, project manager

General Contractor BSI Constructors of St. Louis

Historic preservation Frens & Frens of West Chester, PA

Total square feet 185,000 gross square feet, 160,000 net square feet

Increase to public space added 38,800 square feet for a total of 84,690 net square feet

New Features

The Creative Experience 1,640 square feet dedicated to showcasing new, state-of-the-art technology and software

The Center for the Reader 5,700 net square feet

additional SPACES five meeting room and classroom-type spaces

AUDITORIUM 250-plus-seat area

Teen Lounge 2,200 square feet

CHILDREN’S LIBRARY Added 2,500 square feet for story time and crafts, resulting in 2,000 square feet decicated to collaborative learning and playing space

Public computers 192 (increase of 142)

Staffing 94.5 FTEs (full-time equivalents), increase of 10.5

Costs

Total project cost $70 million includes moving materials out of Central and then back into the library and upgrading two other library-owned buildings in downtown St. Louis

Central Library: $55 million

Central Library construction cost: $45 million, including new or restored shelving

Relocation costs: $2.4 million

Fixtures, furnishings, and technology: $2.5 million, including $500,000 for sophisticated wireless networking equipment, including restoring, refinishing, and retrofitting the original massive carved oak tables with power and network connections

Restoring granite staircase: $1 million

New artwork: $160,000 for cloth wall hangings and enlarged historic photos

Administrative center renovation and moving: $300,000

Compton building upgrade: $2 million–plus

Funding

St. Louis Public Library Foundation $20 million goal, with $2 million remaining

State $2 million in state tax credits used by the capital campaign so that donors could receive a reduction in state taxes

Federal Build America Bonds program, which pays the low interest rate on the bonds

Library $3.4 million from “savings” used for master planning and investigative building work before fundraising

Bonds $45 million in bonds to be repaid with the library’s dedicated property tax income that includes a 1993 voter-approved bump to fund library buildings

A $15 million bond is almost paid off ahead of schedule from the foundation’s capital campaign

Naming rights $3 million, the 250-plus-seat auditorium, which is the only naming opportunity in the Central Library

“Pretty risky”

Initially, SLPL leadership wanted to expand the Central Library to create room for a computer commons and other services, McGuire says. A consultant recommended adding onto the library to meet the needs of 21st-century library users.

The architects at Cannon Design of St. Louis, one of the firms vying to work on the historic Carnegie building, had a different idea. Cannon recommended that we “don’t touch the exterior walls,” McGuire says.

Cannon’s lead architect, George Z. Nikolajevich, says he wanted to respect as much as possible the original design created by Cass Gilbert, the 19th-century architect who also built the U.S. Supreme Court building and New York’s Woolworth Building.

Inspired by Renaissance palaces in Italy, Gilbert designed the Central Library to be constructed of Maine granite, white oak, marble, and Carnegie steel. With high ceilings decorated with molded plaster and carved and painted wood, including one inspired by Michelangelo’s ceiling in the Laurentian Library, the Beaux Arts–style building is often referred to by St. Louis residents as the people’s palace.

Rather than expand the library’s footprint, Nikolajevich and the Cannon team sought ways to preserve Gilbert’s original intent while increasing the space available to the public. As a result, a coal bin became a 250-plus-seat auditorium, while bathrooms and staff locker rooms were transformed into centers for discovering popular books and new technology. Where seven stories of book stacks previously created a fire and earthquake hazard, Nikolajevich found room for a computer commons, a café, a staff lounge, special collections storage, and a northern entrance and service point.

Working inside the existing structure would result in a “huge costs savings,” and Cannon’s ideas found favor with SLPL’s Board of Directors, McGuire says. “It’s pretty risky for architects not to listen to the owners,” McGuire says. “It was really smart of the board. Instead of saying no and getting their back up, they said, ‘We agree. We like their proposal.’?”

Inspiring history

Central Library first opened on January 6, 1912, thanks to Andrew Carnegie’s $1 million gift, half of which was to offset a $1.5 million cost for Central. “It was designed to be a place to be inspired and uplifted,” McGuire says.

At the core of the Central Library was the delivery room, where the public asked for books that were stored behind the scenes in the “stacks” in the north wing, says Abigail Van Slyck, an art history professor and the associate dean of the faculty at Connecticut College, a private liberal arts college in New London, and an expert on the history of Carnegie libraries. The natural light pouring in from three sides is a metaphor for the enlightenment from the books, says Van Slyck. “One of the things that these buildings like the St. Louis Library show us is that we did lose something there in terms of spiritual uplift,” Van Slyck says.

When construction workers removed the main service desk in the delivery room for restoration, they discovered that a century of foot traffic had worn the two-inch-thick marble in front of the desk to a quarter inch. “That’s 100 years of patrons asking for service,” McGuire says. “That means something to a librarian.”

Preparations

In order for the Central Library to close its bronze doors temporarily in June 2010, SLPL had to renovate two other buildings. The entire project cost $70 million. The bulk of the funds came from bonds being repaid by taxpayers and the SLPL Foundation’s capital campaign that had raised $18 million as of March. The foundation only needs to raise $2 million more to meet its $20 million goal. The foundation has become a powerful asset that the library did not have ten years ago, when planning the restoration began, McGuire says. “They did it stepping out in one of the worst economic climates. The library wouldn’t have been able to take it on.”

To free up space for public services, SLPL decided to move all support services from Central across the street to the newly renovated administrative center, which cost $300,000. This opened up space for public use. (SLPL also remodeled 200,000 square feet of the administrative center for a charter high school that pays rent to SLPL, offsetting repayment of the $45 million bond for the Central renovation, according to McGuire.)

Next, SLPL spent more than $2 million to renovate the Compton building, which also acted as a temporary public reference facility for the library’s local history, genealogy, and government documents collections while Central was closed, McGuire says. Compton continues to house SLPL’s digitization center and much of the historic document and serials collections. Some of Central’s collections will remain at Compton. Finally, SLPL staff installed 26 miles of shelving, plus staff, in a former warehouse to store temporarily most of Central’s four million items, so that collection could be shipped to SLPL’s 16 other branches while Central was closed.

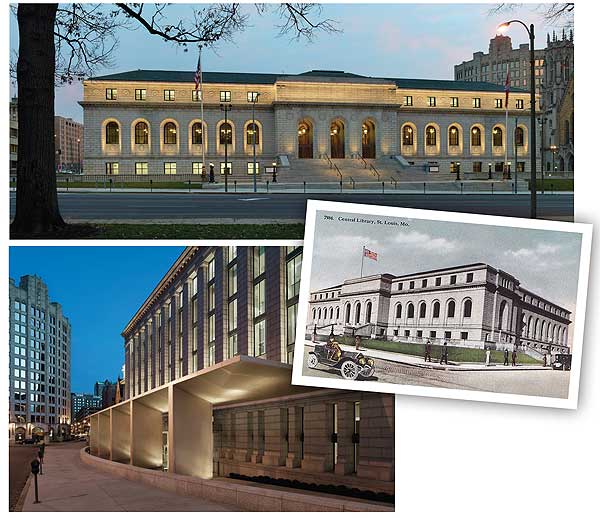

DEFT TOUCHES SLPL’s historic facade, both today and yesterday (inset). Engraved with thousands of titles from the library’s collection, a stainless steel canopy arises from a pool of water outside the new north entrance. The canopy shelters visitors but doesn’t touch the historic facade. Photos ©Timothy Hursley. Postcard courtesy of SLPL

As a result of moving the administrative offices, Central Library opened up 38,800 square feet of public space for a net total of 84,690 square feet, says Lynn S. Grossman of Cannon Design and one of Central Library’s project architects (along with Matthew Huff). To meet the demand for increased services at Central, 10.5 full-time equivalent employees (FTE) were added, totaling 94.5 FTE, McGuire says.

Removing the stacks

One major challenge the architects and library leaders faced was Central’s confined seven stories of bookshelves built like “tinker toys” on top of one another, McGuire says. Glass floors separated each cramped section of the stack tower. “I’m six-four, and I had to duck in some places in the stack tower,” he says.

Closed to the public, the stacks floated like a separate structure within the walls of Central’s north wing. Yet what made the “stacks” a 19th-century engineering feat also made them a modern fire and earthquake hazard for the staff, say architects and library leaders.

Cannon’s Nikolajevich says he was inspired by the idea of a building floating within a building. The architect converted the north wing housing the stacks into an atrium. He then used glass walls for the computer commons planned for the second floor and new staff rooms and special collections storage on the third floor to create the appearance of floating rooms. “The trick is to find the balance in new and old,” Nikolajevich says.

OLD AND NEW Modern lighting, including book shelves illuminated with LED lights, brighten the adult literature room, which will be renamed the Waller F. McGuire Room. The oak tables and the painted ceiling beams were cleaned and restored. Photo ©Timothy Hursley

Once the stacks were removed from the north wing, light poured in from the windows that Gilbert designed, flooding the space. Through the glass, the library was now connected to Lucas Park in a way it hadn’t been, says Lynn S. Grossman, the Central Library’s interior architect. “The first time we saw that space and the windows open to the park, it was just breathtaking,” Grossman says.

To give the public a northern entrance, a few lower windows were converted into doorways to the atrium, channeling patrons to an information desk. Outside the entrance, Nikolajevich designed a 15-foot-tall stainless steel canopy that appears to float on a reflecting pool to shelters library patrons from the elements, McGuire says. The canopy does not touch the historic façade.

The public submitted their favorite quotes from works found in the library, and 10,000 phrases were engraved into the steel. “That was George Nikolajevich’s baby,” McGuire says. “After he designed it, I wanted to scribble all over it.”

Auditorium

The new auditorium and restored Great Hall have attracted outside groups interested in the library as a venue for special events. The Partnership for Downtown St. Louis held its gala fundraiser in the Great Hall in January, shortly after the library reopened. Acknowledging the interest in the library as a venue, the SLPL Foundation has funded an events coordinator, McGuire says. The library is seeking a partner willing to pay $3 million for naming rights to the auditorium.

OPENED UP The new north atrium offers views of a computer commons and the special collections (the latter is closed to the public). The atrium takes the place of seven stories of closed stacks, with glass floors that were a fire and earthquake hazard, and gives the library a north entrance onto Lucas Park. Photo ©Timothy Hursley

Open on Sundays

On the first floor, gutting offices, aging bathrooms, and a staff locker room resulted in a gain of 12,260 square feet, bringing the total to 29,710. This space houses the Center for the Reader, the teen and children’s areas, and popular nonfiction titles, such as science and technology.

By collocating all the more popular items on one floor for easy access by library users, Central staff also can open just the first floor, allowing the library to open on Sunday with a skeleton crew. “It hasn’t been opened on Sundays before. On Sundays, we only open the first floor and that is manageable and affordable,” McGuire says.

The children’s library has increased by 2,500 square feet for story time and crafts and been brightened with quotes from children’s books and colorful statutes.

A glass wall striped in rainbow colors and “DREAM” in huge white letters marks the 2,200 square foot teen lounge and invites teens inside to Central’s first dedicated teen space.

Nearby, musically inclined patrons can mix their own CDs in a recording studio, while the Creative Experience offers 1,640 square feet dedicated to showcasing state-of-the-art technology, interactive computing, and collaborative learning and play, McGuire says. “We wanted to create these areas of delight and serendipity and appeal.”

Grand stairs and hall

The granite staircase to the second floor entrance on Olive Street required $1 million as construction crews numbered each granite slab as it was removed. The structure beneath the steps was repaired, and stoneworkers then reassembled the granite blocks like a giant puzzle, McGuire says.

Once up the stairs, patrons walk through the Olive Street lobby and proceed into what many call the heart of Central Library, the Great Hall Reading Room, which lovers of the library describe as the spirit of the building and a symbol of the illumination that libraries bring to communities. As part of the restoration, the bronze tubes once used for delivering books were saved and polished. The ornamental ceiling plaster was repaired from damage incurred during the 1950s when fluorescent lights were installed, according to Cannon architects.

ENGAGING YOUNGER PATRONS (Top): Teens are invited to “DREAM” in the new 2,200 square foot teen lounge, with typography and rainbow glass designed by Deanna Kuhlmann, a St. Louis graphic designer. (Bottom): The children’s area was also expanded, with an additional 2,500 square feet for story time and crafts, and brightened with quotes from children’s books and designs also created by Kuhlmann. Photos ©Timothy Hursley

On the second and third floors, crews discovered space under the marble floors left by the 19th-century craftsmen where they could now install wires for electricity, cables, and routers for Wi-Fi and other technology, Grossman says. Hidden ventilation shafts designed by Gilbert were now going to accommodate modern wiring, heating, and cooling ducts and fire protection systems. “This was amazing, forward-thinking by Cass Gilbert,” Nikolajevich says.

Renovated light fixtures and LED lights in stacks increased illumination. Enclosed on two sides with glass, a computer commons brings in light from the windows in the north wing’s atrium.

Another challenge of a historic library was to create an intuitive flow from one section to another and locate resources so users could conveniently find them, McGuire says. The fine arts and architecture rooms are located near the library’s literature and performing arts collections. Government documents and resources for business, law, and languages are clustered together. Philosophy, religion, psychology, and social sciences also are located together. “It was another way to make this very remarkable and structured building work for us,” McGuire says. “We tried to design connectivity.”

CREATING SPACE (Clockwise from above l.): The frescoes, bronze, and marble were restored and renovated in the Olive Street foyer as part of the $70 million restoration of SLPL. Five rooms were added to the library for training or meetings. The Creative Experience features interactive computer screens and space devoted to new technology and collaborative learning and is located on the library’s first floor. Photos ©Timothy Hursley

Away from the bustle

By removing the warren of offices from the third floor and returning to Gilbert’s original walls, the library’s public space increased by almost five times, from 4,020 square feet to 19,360 square feet. Modern compact shelving prevented the rooms from feeling overwhelmed, McGuire says.

Stairwells with stained glass windows were opened to the public, and, in the Carnegie room, a skylight was rediscovered. Historic photos were reproduced, enlarged, and hung.

The third floor now holds genealogy, St. Louis studies and history, plus rare book and special collections, all collocated to make things easier for researchers. The furnishings are configured to serve people who will spend days on projects, but, at the same time, the worktables don’t isolate the library users. “The genealogists, for example, are a passionate bunch who like that they can work away from bustle and that they can form connections across the table,” McGuire says.

Economic impact

Besides having a place in the hearts of St. Louis residents, the restoration of Central Library also put money in the community’s pocketbook and helped the decade-long revitalization of the city’s downtown core.

Since construction began on Central in 2010, three other downtown buildings have been developed as mixed-use projects, providing housing and commercial sectors and making a “significant impact,” says Maggie Campbell, president and CEO of the Partnership for Downtown St. Louis, which manages the 165 square block Downtown St. Louis Community Improvement area. According to Campbell, in recent years, the downtown has been the fastest growing residential neighborhood in the region.

The restoration project was projected to create 431 direct and indirect jobs, according to a 2009 economic impact study commissioned by SLPL. Multiplier effects were expected to pump an additional $120.8 million into the regional economy, according to the study by Development Strategies, a St. Louis-based economic development consulting firm. McGuire says that when construction was under way, an average of 100 people were working on the project. Many of the contractors and artisans on the project are based in the city, he says.

The library board hired contractors that employed women and minorities, McGuire says. In St. Louis, minorities make up 56.1 percent of the population, and 26 percent of the city’s 318,000 residents live below poverty level, according to the Bureau of the Census’s 2012 estimates. The board felt the focus on diversity helped many people during the recession and has since decided that the library should continue this policy. “We’re a challenged city—economically challenged and educationally challenged,” McGuire says. “Like many cities, you have great wealth and great poverty cheek to jowl.”

As for the impact on the library’s own economics, though there are a few construction tasks remaining, McGuire says he expects the project will come in two or three percent under budget.

Marta Murvosh, MLS, is a freelance writer/researcher and aspiring librarian living and working in Northwestern Washington. You can follow her via www.facebook.com/MartaMurvosh

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!