Murder, Smog, and Communist Intrigue in Hold Your Breath, China

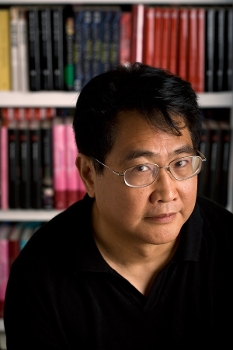

In 1988, Qiu Xiaolong came to St. Louis, planning to stay for one year at Washington University to research T. S. Eliot, whose poems he’d translated. Following political upheaval in China, Xiaolong decided to make his home in America.

Qiu Xiaolong’s latest crime thriller reveals the toxic machinations of the CCP.

In 1988, Qiu Xiaolong came to St. Louis, planning to stay for one year at Washington University to research T. S. Eliot, whose poems he’d translated. Following political upheaval in China, Xiaolong decided to make his home in America. Qiu Xiaolong’s Inspector Chen novels, which explore life in contemporary China, have been translated into twenty languages and sold two million copies. In Hold Your Breath, China, Inspector Chen confronts murder and government corruption against the backdrop of an environmental crisis.

You started your career as a poet in 1978. Why did you start writing detective fiction?

Because of what happened in Tian’anmen Square in 1989, and my support of the students in Beijing, the police warned my family in Shanghai. I was unable to go back to China for seven or eight years. When I finally did, so impressed by the changes, I wanted to write a book about Chinese society in transition. Having not written a novel before, I “borrowed” the framework of the detective fiction. With a cop walking around the city, knocking on doors, and having access to governmental secret files, the genre served my sociological purpose well.

framework of the detective fiction. With a cop walking around the city, knocking on doors, and having access to governmental secret files, the genre served my sociological purpose well.

This book was inspired by a real online environmental documentary. What impact did that film have in China?

The real documentary is titled “Under the Dome,” and it was made by a courageous journalist named Chai Jing. She had worked in China Central TV, but after the release of the documentary, she practically disappeared from public view. I think the film introduces much more environmental awareness to Chinese people, whether the government liked it or not. For the last ten years or so, I went back to China every year for my book research. Every time I got sick there with symptoms of acute bronchitis because of the terrible air quality.

You said that, while researching this book in China, “I knew I was being constantly watched.” Was the surveillance out in the open?

I was warned a number of times by the people I knew. (“We know what you are writing.” “You have just done an interview with a German newspaper. Don’t think we do not know.”) Here is what happened last year: I was sitting out on the balcony of an Australian friend’s home in Shanghai, talking with several other people, when a small drone came buzzing overhead. For an hour or so, the drone kept circling above us until we rose to go back into the room. According to my host, cameras were installed both above and beside the balcony, but perhaps because of me, the ordinary cameras were not enough for the “Heavenly Net” system the Beijing government boasts of. So there came the drone.

You write that the Chinese government has “stability maintenance” policies to handle “sudden eruptions of people’s protests” in the age of social media. How are those policies working?

For an appearance of stability, the Party authorities spare no cost. During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in China, a doctor named Li Wenliang in a Wuhan hospital wrote in a WeChat post that a deadly, highly contagious SARS-like virus was breaking out in China. The  government wanted a complete cover-up and demanded he write a guilty plea for disrupting social stability. Dr. Li had no choice but to sign his name on the guilty plea. Shortly afterward, he was infected with the virus, and on his death bed, he showed his guilty plea to journalists. Even today people are still mourning him as the victim of “stability maintenance.”

government wanted a complete cover-up and demanded he write a guilty plea for disrupting social stability. Dr. Li had no choice but to sign his name on the guilty plea. Shortly afterward, he was infected with the virus, and on his death bed, he showed his guilty plea to journalists. Even today people are still mourning him as the victim of “stability maintenance.”

Do you see any parallels between how Beijing has responded to COVID-19 and the air pollution problem?

Yes, the parallel is so obvious. An appearance of everything being fine is absolutely needed for the governmental propaganda. While well-aware that the coronavirus was capable of human-to-human transmission, Party authorities nonetheless declared that it was not contagious among people. If anyone said otherwise, they were silenced and punished. Eventually, the governmental cover-up led to a disaster in China, and throughout the world too.

Growing up in Shanghai, what was your family’s view of the national government?

It was not something my parents would have discussed with me. My father ran a small factory before 1949, and when the Communists came to power, he became a “black” capitalist in Mao’s theory of class struggle. In other words, a target of the “proletarian” dictatorship. During the Cultural Revolution, he was relentlessly persecuted as a “black monster” because of that. And I was a “black puppy” by his side.

One character has a “twenty-three-year-old dependent addicted to computer games.” Is this a widespread phenomenon?

There’s a new word, “parents-eating class” (kenglaozhu), which has crept into the Chinese language in recent years. They are no longer that young, but instead of working to make a living for themselves, they see no problem in being totally dependent on their parent, as if eating them. It’s not something I saw in my younger days. With the traditional value system totally gone under the CCP rule, “things fall apart; the center cannot hold.”

Sponsored by

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!