Interpreting Shakespeare: Discover The First Folio

Learn from The Arden Shakespeare Fourth Series general editors how different versions of Shakespeare’s plays can significantly alter their interpretation, and explore how Drama Online’s resources can support understanding of different textual interpretations through the play scenes and book chapters.

Peter Holland, Zachary Lesser and Tiffany Stern

General Editors for The Arden Shakespeare Fourth Series

Learn from The Arden Shakespeare Fourth Series general editors how different versions of Shakespeare’s plays can significantly alter their interpretation, and explore how Drama Online’s resources can support understanding of different textual interpretations through the play scenes and book chapters referenced below. Please note that linked play, book and selected video content (scenes from Shakespeare’s Globe productions of Macbeth, The Tempest and King Lear) are free to view this term; other referenced video content is only available to those with access to the relevant Drama Online video collections.

Editors for The Arden Shakespeare Fourth Series (due to launch on Drama Online in late 2024) are reconceiving Shakespeare for the 21st Century. Among all the other early texts which they will be addressing in detail, there is the play collection known as Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623). A ‘folio’ describes a large book made of sheets of paper folded only once.

The manuscripts behind the First Folio do not all have the same origin: some may have come from pre-performance texts, some from prompters’ books, some from transcripts for readers, some from court versions. Editors must work out which version of the play is behind their text, and, if there are also alternative ‘quarto’ or ‘octavo’ texts, (books made from papers folded two or three times) how those often different versions relate to the First Folio.

Critically, the editors will also need to decide what moment in the life of the play to work towards. This might be the manuscript Shakespeare gave the company, the play put on in first performance, the play as revived or revised, the court version, or perhaps a readers’ transcript. These decisions will be made on a text-by-text basis in the light of what the First Folio (and quartos/octavos) have revealed. The result will foreground the complexity of the printed text, and the important detective work that editors face when recovering and reconstructing texts.

Below, Peter Holland, Tiffany Stern, and Zachary Lesser explore how seemingly small textual differences can significantly impact our understanding of a play, working with The Tempest, King Lear and Macbeth.

The Tempest

Arden 4 General Editor: Tiffany Stern

The Tempest only survives in the First Folio, so there aren’t any other versions of the play to consider. But what text does the First Folio supply? We know from court records that The Tempest was put on in front of King James at Whitehall in 1611, and that it was later performed at court in 1613 for the wedding of Elizabeth Stuart and Frederick V, Elector Palatine. Given the long wedding masque in the play – a masque that does not entirely fit its context – the First Folio text may well preserve the 1613 court performance, and it is important to try to recover that grand occasion, its colours, its candles, its courtly audience and their servants, when editing the text. For a characterful description of the meaning of the wedding masque as well as why it might have been cut short, see Shakespeare Uncovered: The Tempest here, which also addresses other major themes including how biographical the play may be. Introduced by director Trevor Nunn, the programme includes snippets of famous productions of The Tempest over the years and looks at what happens when a male Prospero is replaced by a female one.

The Tempest only survives in the First Folio, so there aren’t any other versions of the play to consider. But what text does the First Folio supply? We know from court records that The Tempest was put on in front of King James at Whitehall in 1611, and that it was later performed at court in 1613 for the wedding of Elizabeth Stuart and Frederick V, Elector Palatine. Given the long wedding masque in the play – a masque that does not entirely fit its context – the First Folio text may well preserve the 1613 court performance, and it is important to try to recover that grand occasion, its colours, its candles, its courtly audience and their servants, when editing the text. For a characterful description of the meaning of the wedding masque as well as why it might have been cut short, see Shakespeare Uncovered: The Tempest here, which also addresses other major themes including how biographical the play may be. Introduced by director Trevor Nunn, the programme includes snippets of famous productions of The Tempest over the years and looks at what happens when a male Prospero is replaced by a female one.

|

The Tempest, RSC, 2016 |

The Tempest in the First Folio has a crucial textual crux: a speech prefix. In the Folio, ‘Mira’ (the speech prefix for Miranda) calls Caliban an ‘abhorred slave’, adding that he is ‘vicious’, ‘savage’, ‘brutish’, and of a ‘vile race’. Caliban retorts: ‘you taught me language, and my profit on’t is, I know how to curse’. This exchange has long been the focus of discussion because of the attitude it reveals towards race and slavery, some of which can be read here, in The Tempest: A critical reader, and some here, in the introduction to Arden 3’s The Tempest. The ‘abhorred slave’ speech has, from the 1667 adaptation of The Tempest by John Dryden and William Davenant, been given to Prospero, the argument being that its tone of bitterness and anger fits with his other speeches; and, in practical terms, that Miranda is unlikely to have been able to teach Caliban how to curse when she arrived on the island as a three-year-old child. Theobald in 1733 added that for Miranda to speak in this forthright manner would show ‘impropriety’ bordering on ‘indecency’. The Folio speech heading was, however, returned to Miranda last century, and Miranda was reassessed as an empowered woman speaking roundly to her would-be rapist. Gender roles as a prominent, but changing, thematic concern in The Tempest are discussed here in Brinda Charry’s The Tempest: Language and Writing.

|

The Tempest, Shakespeare’s Globe, 2013 |

Different productions on Drama Online show how the speaker of the ‘abhorred slave’ lines – and the way they are spoken – have a huge effect on our interpretation of the text. In the all-female production of The Tempest at the Donmar Warehouse, directed by Phyllida Lloyd in 2019, it is an enraged Prospero (Harriet Walter) who speaks the speech to Caliban (Sophie Stanton), while Miranda (Leah Harvey), escapes under the bed, devastated by memories of the attempted rape. But a forthright Miranda (Jenny Rainsford) boldly speaks it here, in the 2016 RSC production directed by Gregory Doran; a touching, troubled Caliban (Joe Dixon) responds ‘you taught me language’ to Prospero (Simon Russell Beale) in a haunting, melancholy rendition of the scene. By contrast, , directed by Jeremy Herrin in 2013, is upbeat. In it Caliban (James Garnon) is endearingly painted to look like the Globe’s pillars – as though the island, and perhaps the theatre too, is ultimately on his side – but the speech is still spoken by an incensed Miranda (Jesse Buckley), as her concerned father Prospero (Roger Allam) clutches his staff. While in Antoni Cimolino’s Stratford Festival production (Stratford, Ontario) of 2019, Miranda (Mamie Zwettler) is sweet and Caliban (Michael Blake) bitter; it is still Miranda who gives the speech, but in this production ‘slave’ is replaced with ‘brute’.

Just one speech-heading in the First Folio can take us to key critical issues of the play, and to a rich range of performance choices, each one having a different bearing on race and gender.

King Lear

Arden 4 General Editor: Peter Holland

‘The King is coming.’

‘The King is coming.’

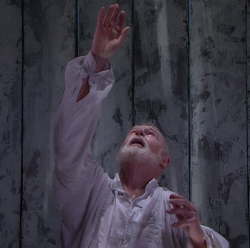

We knew, as King Lear started, that sooner or later the King would make his entrance. Sometimes Shakespeare delays the title-character’s first appearance for some time. In Hamlet it takes a long scene of some 180 lines with Horatio and the guards seeing the Ghost. In Macbeth, we are over forty lines into the third scene (and over 110 lines in all) before Macbeth arrives onstage. In King Lear, it is a mere thirty lines in the first scene: there is a brief exchange between the Earls of Kent and Gloucester about the King’s division of the kingdom and the relative shares the Dukes of Albany and Cornwall are to get, and then a switch of topic as Kent is introduced to Gloucester’s illegitimate son Edmund, and Gloucester talks about Edmund’s conception in a way that is unpleasant, coarse, almost a parody of what we might now call locker-room chat. Then Gloucester sees that ‘The King is coming’. Derek Jacobi who is a white man with a white beard plays King Lear wearing a white shirt and stretching an arm into the air whilst looking to the sky

|

King Lear, Donmar Warehouse/

|

How does Lear make that entrance? In Richard Eyre’s 1998 BBC film, based on his production at the National Theatre, Gloucester’s line is almost nervous. A brief trumpet call and the three daughters almost run into the room, then Albany and Cornwall, and finally Ian Holm’s Lear enters at speed accompanied by two servants with flaming torches. All settle at the conference table. Lear orders Gloucester, barely settled in his chair, to leave to ‘attend the lords of France and Burgundy’ and is irritated that Gloucester takes the map with him, shouting at him ‘Give me the map there’. This strong, almost youthful Lear finds the idea that he is about to ‘crawl unburdened toward death’ funny.

|

King Lear, Shakespeare’s Globe, 2017 |

There is strength, too, in Kevin McNally’s Lear in Nancy Meckler’s 2017 Shakespeare's Globe production. His announcement of the crawl toward death elicits a cry of ‘Oh no’ from the court, which he soothes, again with a laugh as he adds ‘No, no, no, no’ to Shakespeare’s text. But, a few lines later, he needs to be reminded by Kent of the names of Cordelia’s suitors, even though he has correctly named them in his first words, a sign of age, of failing memory, of what will come. Derek Jacobi in a Donmar Warehouse/National Theatre Live production in 2010, though closest in age to Lear’s ‘fourscore and upward’, strode onto the stage full of energy, hand in hand with Cordelia, most concerned about the huge map unrolled onto the stage floor in from of him. Vigorous, easily controlling, always on the move, this Lear will have a long way to fall as the play’s road for him unwinds.

For the RSC in 2016, David Troughton calls out the news of Lear’s arrival as a public announcement. To the sound of chiming bells and male voices chanting, the stage slowly fills with people, first one carrying a giant golden disc, then the daughters and courtiers and more attendants, four of whom carry Lear in high on their shoulders, the king seated on a throne inside a glass box that, when lowered, leaves him effectively immobile, six feet above the stage-floor and still quite far upstage. This Lear’s voice quavers, his age strongly apparent, his distance from all strongly marked. It is an image of kingship at once glorious and vulnerable, powerful but isolated.

All four follow the First Folio’s form of the entry, and not one heads up the entry with ‘one bearing a coronet’, as the First Quarto did. All include Lear’s image of his future when ‘we / Unburdened crawl toward death’, lines present in the Folio but not the Quarto. Four very different productions but each engaging with (more or less) the same text, each exploring its own possibilities of the play’s multiple potentialities, each calling out for us to compare and contrast, to see how the tiny details of their choices here speak to their vision of Shakespeare’s extraordinary play.

Macbeth

Arden 4 General Editor: Zachary Lesser

Among the most famous of Shakespeare’s creations are the Weird Sisters in Macbeth, glimpsed here in Polly Findlay’s 2018 RSC adaptation. These witches are “weird” not in the modern sense of the word (bizarre or abnormal), but because they are intertwined with destiny and fate, deriving from the Old English wyrd. The Weird Sisters have a life beyond the play: they pop up as the band that plays at the Yule Ball in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire; they lend their name to several novels, to clothing boutiques and yarn stores, to publishing companies and podcasts. But the Weird Sisters appear nowhere in the original text of Macbeth, printed in the 1623 First Folio. There the witches, described here in Shakespeare’s Demonology, are called either weyward (an early spelling of wayward, meaning disobedient, uncontrollable, or perverse) or weyard (a word otherwise unknown). Are these two variations of the same word? Is weyard simply Shakespeare’s phonetic spelling of weird, a word that his contemporaries pronounced with two syllables?

Among the most famous of Shakespeare’s creations are the Weird Sisters in Macbeth, glimpsed here in Polly Findlay’s 2018 RSC adaptation. These witches are “weird” not in the modern sense of the word (bizarre or abnormal), but because they are intertwined with destiny and fate, deriving from the Old English wyrd. The Weird Sisters have a life beyond the play: they pop up as the band that plays at the Yule Ball in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire; they lend their name to several novels, to clothing boutiques and yarn stores, to publishing companies and podcasts. But the Weird Sisters appear nowhere in the original text of Macbeth, printed in the 1623 First Folio. There the witches, described here in Shakespeare’s Demonology, are called either weyward (an early spelling of wayward, meaning disobedient, uncontrollable, or perverse) or weyard (a word otherwise unknown). Are these two variations of the same word? Is weyard simply Shakespeare’s phonetic spelling of weird, a word that his contemporaries pronounced with two syllables?

|

Macbeth, Stratford Festival (Ontario), 2013 |

The weyward or weyard sisters did not become weird until nearly a century later, in 1733, when the editor Lewis Theobald inserted the word, arguing that “the word Wayward has obtain’d [in the First Folio] … from the Ignorance of the Copyists, who were not acquainted with the Scotch Term [weird].” Theobald was correct that, in Shakespeare’s day, the word weird was almost always used in texts written by Scottish people, published in Scotland, or about Scotland. It was not a word commonly heard in London. Emma Smith, Professor of Shakespeare Studies at the University of Oxford, writes further on the alternative spellings here, in her critical work Macbeth: Language & Writing. If Shakespeare did mean to call his witches the Weird Sisters, we can therefore see the word weird as part of his exoticizing project for the play as a whole, depicting a Celtic periphery where uncanny events might seem, to an English audience, plausibly to occur. Like other particularly “Celtic” words in the play (thane, kern, gallowglasses), the weird sisters imbue the play with a linguistic aura of otherness that was part of its appeal to London audiences.

|

Macbeth, Shakespeare’s Globe, 2013 |

But we have a lot of evidence that the witches were more commonly known as the wayward sisters. In the seventeenth century, virtually all the references to these characters think of them as wayward, not weird. For instance, Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome’s The Late Lancashire Witches, first performed in 1634 and influenced by Macbeth, has one character tell another: “you look like one o’ the Scottish wayward sisters.” So perhaps this was the phrase that audiences heard when they went to the earliest performances of Macbeth at Shakespeare's Globe. (See left for a modern performance of Macbeth from 2013 at the reconstructed Globe.) What would it mean to think of the witches as the Wayward Sisters rather than the Weird Sisters?

Wayward was an adjective commonly applied to two classes of people imagined to be prone to disobedience against proper authority: children and women. In a typical expression of this kind, Shakespeare has Antipholus of Ephesus say in The Comedy of Errors: “My wife is in a wayward mood today.” If the witches are the Weird Sisters, our attention is drawn to their possible control over Macbeth’s actions, their management of his fate, their supernatural insight into the future. If they are the Wayward Sisters, these issues do not disappear, but we might think of the witches more in connection with other aspects of the play dealing with gender hierarchy and “wayward” women: the marriages of the Macbeths and Macduffs; Lady Macbeth’s “unsex me here” soliloquy; the special power granted by being “unknown to woman” (Malcolm) or “not of woman born” (Macduff).

Ultimately, we do not know what word Shakespeare wrote in his manuscript, or what word the King’s Men spoke on the Globe stage. Since 1632, with the publication of the Second Folio, every editor of Macbeth has had to decide what to call these witches. And theatre directors, such as Rufus Norris at the National Theatre in 2018, must make the same decision. The more we know about Shakespeare’s texts, the more possibilities we can find in them.

Visit our Previously Featured Content page to view other topics including The Plays of Caryl Churchill, Women in Shakespeare, Drama without Borders: Stories of migrants and refugees, The Climate Crisis in Theatre, Black British Playwrights, and LGBTQ+ Playwrights.

Read LJ's eReview of Bloomsbury Video Library here

SPONSORED BY

Is it possible to get the Mean and Standard Deviation values you used across the key metrics for the LJ 2022 star ratings of libraries in the $10M-$29.9M with a LSA of 100k-250k? If I use the posted data for star libraries reported, using your formulas, I don't get anywhere near the same scores. I assume it is because I am using a small sample of 13 libraries to calculate the Mean and StdDev.

For example if I calculate the Mean & StdDev for the libraries in the $10M-$29.9M category with a LSA of 100k-250k (13 libraries) and use that for the calculations

(((Lib data -Peer Pop Mean) / Peer Pop StdDev) +8) *100 I get a Score of 1,551 for Naperville instead of the 2,669 in the report. I do sum the scores for each category before I add the 8 as shown below

Naperville Public Library

Physical Circulation 22.52

Minus Physical Circulation Mean 11.73

= 10.79

Divided by Physical Circulation StdDev 6.98

score for circulation = 1.551

Circ Score 1.55 Em Score -0.05 Visit Score 2.71 Prog Attnd Score 1.09 Comp Use Score 1.82 Wi Fi Session Score 0.39 ER Score Raw 2.14 Score Sum 7.51 + 8 = 15.51 x100 = 1551

And so on for each key category. The results for each category are added up, 8 is added and that sum multiplied by 10 as per your 7 Step "Score Calculation Algorithm"

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing