City Librarian: John Szabo Is LJ’s 2025 Librarian of the Year

Los Angeles Public Library director John F. Szabo connects with every corner of his adopted city through innovation and compassion.

|

LOVING L.A. Los Angeles City Librarian John F. Szabo, in LAPL Central Library’s Tom Bradley Wing. Photo by Corey Kennedy |

Los Angeles Public Library director John F. Szabo connects with every corner of his adopted city through innovation and compassion

Official titles for American library directors vary among municipalities and don’t reflect the particulars of their job or talents—a leader designated as library president or CEO is no more businesslike than their counterparts whose job title is commissioner or county librarian. Sometimes, however, the designation fits the individual exceptionally well.

Official titles for American library directors vary among municipalities and don’t reflect the particulars of their job or talents—a leader designated as library president or CEO is no more businesslike than their counterparts whose job title is commissioner or county librarian. Sometimes, however, the designation fits the individual exceptionally well.

John Szabo, director of Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL), is the 20th City Librarian of Los Angeles—and he is, in every way, the city’s librarian. He is not a native Angeleno, yet in his 12 years at LAPL Szabo has taken the genuine love of community that made him a compassionate and effective leader at his first library job, in a small, rural town of 8,000 residents, and scaled that up to serve a diverse urban population of nearly four million across 503 square miles.

Szabo has aligned the library’s work with citywide priorities that include homelessness, serving immigrants, health, and literacy, and has nurtured its partnerships with hometown organizations from the zoo to the Dodgers. When the owners of Angel City Press, a local, Los Angeles–focused independent publisher, retired, they gave the press to LAPL, citing Szabo’s deep interest in L.A.’s history and cultural life. The Library Experience Office’s trauma-informed practices, the New Americans initiative, the buoyant L.A. Libros Book Festival—these and many other services speak to Szabo’s love for his adopted city and empowerment of LAPL’s 1,500 staff members to help drive innovation, and are the reasons he is LJ’s 2025 Librarian of the Year, sponsored by Baker & Taylor.

FROM COMMUNITY THEATER TO BIG-CITY STORIES

Szabo grew up an only child, raised by his father since he was 10, and spent a lot of time in libraries. Even more than the books themselves, though, he was fascinated by what made the library tick. “Some kids want to be an astronaut, or motorcycle racer,” says Szabo. “My ultimate fantasy was to somehow get behind that desk and figure out how all those machines worked.”

Szabo soon found himself on the other side of the desk, making $3.15 an hour in high school as a library clerk at Gunter Air Force Station in Montgomery, AL. While earning his bachelor’s degree in telecommunications from the University of Alabama, he worked in the interlibrary loan office for women who encouraged his hunger to learn.

It’s little surprise, then, that when Szabo went on to earn his master’s in information and library studies at the University of Michigan, his goal was to be an interlibrary loan officer at a small college. But his focus shifted thanks to Michigan’s Head Librarian program, which allowed MLS students to run small libraries within each residence hall for a $300 monthly stipend and an apartment. “You supervised a very tiny staff of undergraduates who often came to work in their pajamas,” Szabo recalls. He was in charge of programming and collection development, with the mandate to serve a highly diverse community. “Even though it was in a university environment, it had the flavor of a public library,” he says. He was sold.

Fresh out of library school, Szabo, on a lark, applied for a director position at the Robinson Public Library District, in southern Illinois—and got the job. Because he knew no one there, one of his first moves was to land a role in a community theater production of Oklahoma!. Musical theater led to friends and connections. “I was completely head over heels in love with public librarianship and being the public library person in town,” he says—a sentiment that has never changed, even as the libraries he leads have.

Szabo moved on to 10 years of directorships in Florida—Palm Harbor Library and then the five-branch Clearwater Public Library System—and in 2005 took the helm at his first large urban institution, Georgia’s Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System, for seven productive years.

The move to Los Angeles took Szabo somewhat by surprise. “I never thought of myself as a West coaster,” he says. But during the interview process, when he met with then-Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, the two found they were on the same page on ways the library could help advance city health initiatives, getting the sense that “L.A. seemed to be fertile ground for wild, out-of-the-box thinking,” and that the library—and city—could be a good match for his ideas.

“A THOROUGH ANGELENO”

Szabo quickly became an enthusiastic lover of all things Los Angeles, and began thinking of ways LAPL could celebrate the city’s stories—starting with its special collections of photographs, maps, restaurant menus, fruit crate labels, and other historical L.A. material. Relocating Angel City Press to the library last year has reinforced the library-as-storyteller ethic. “John had the vision to make this happen,” says editorial director Terri Accomazzo. “He saw what this could do for the library and for the press.”

“He really has made himself a thorough Angeleno,” says L.A. Deputy Mayor Jacqueline Hamilton. “He knows the city inside out.”

|

BRIGHT LIGHTS IN A BIG CITY Top: Szabo and staff from the Library Experience Office, including Supervising Social Worker Edna Osepans (second from right), were recognized along with other community organizations by the Los Angeles City Council during Overdose Awareness Month. Middle: Szabo was joined by some of the youngest Angelenos to launch Read, Baby, Read!, a program where LAPL collaborates with hospitals, health care providers, daycares, and early childhood education centers to provide a library card for each baby along with early literacy information to expectant and new parents. Bottom: Szabo and Associate Director for Community Engagement and Outreach Madeline Peña Feliz at LAPL’s Los Angeles Libros Festival. Photos courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library |

Hamilton had read Susan Orlean’s The Library Book, about the catastrophic 1986 LAPL Central Library fire and its aftermath, so when she stepped into her role in 2023, she was delighted—Szabo “was a little bit of a rock star to me,” she says. “It’s a real privilege to work with someone like him. John is completely dedicated to service, and he shows it by bringing his considerable intellect to creative problem solving and thinking very broadly about the role that libraries play in the 21st century.”

She points to LAPL’s early adoption of Career Online High School, a free program that allows adults 19 and older to earn a high school diploma; English as a Second Language and Spanish literacy programs; and the Octavia Lab, a makerspace (named for Octavia Butler) that enables creative work from podcasting to state-of-the-art digital media, among others. That support extends to other departments; 100-year-old ephemera from the El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument, which the city was concerned about safely storing, now has a home in the library archives.

Although not in Atlanta when it hosted the 1996 Summer Olympics, Szabo saw how they benefited the city—and is looking forward to 2028, when the games will come to L.A. for the third time. LAPL is already in on the action, helping City Hall with memorabilia and artifacts for an exhibition about the history of the games in L.A. “The library has an original program from the 1932 Olympics, and [Szabo] knew it was there,” says Hamilton “He helped his staff pull together these exhibits.”

The L.A. Dodgers offer LAPL free giveaway baseball caps and jerseys, and players come to the library to read. “It sends a message that we are of and about L.A., and we are proud of L.A.,” says Szabo. “And it also says that we’re cool.” If that was ever in doubt, in 2021 Central Library hosted the tween/teen punk girl band The Linda Lindas for a wildly viral performance; they went on to a national record deal.

The library’s social media presence is engaging and extremely popular, says former LAPL Board President Bích Ngọc Cao, in no small part because “John has empowered the staff to create marketing and social media strategies that are really fun and inspiring.”

Szabo “seems to have his finger on the pulse of what’s going on,” says Associate Director for Community Engagement and Outreach Madeline Peña Feliz. “He’s really clued in to the city as the library can serve it.”

|

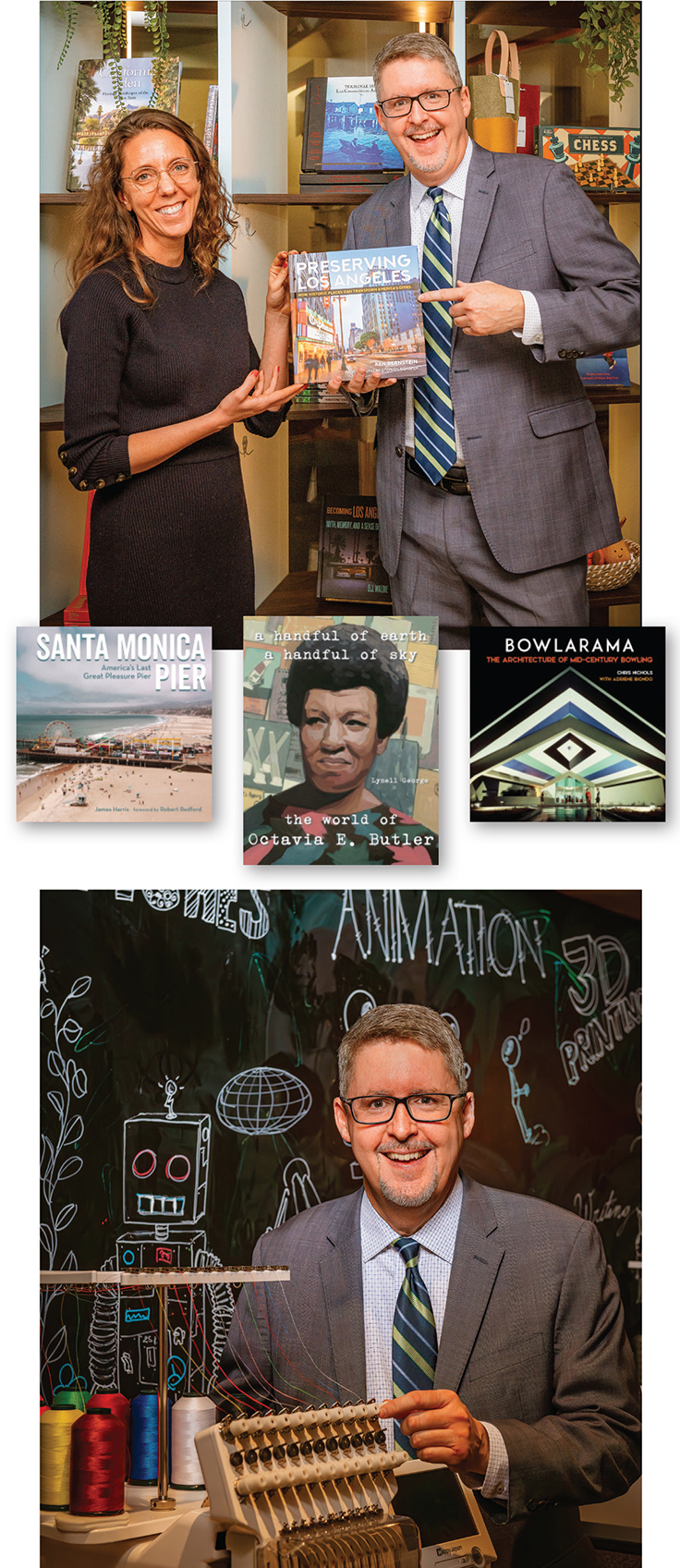

ARTS AND SCIENCES Top: Szabo and Angel City Press Editorial Director Terri Accomazzo show off one of the press’s titles (more titles shown below the photo). Bottom: Szabo checks out the embroidery machine at the Central Library’s Octavia Lab. Photos by Corey Kennedy |

STRATEGIC THINKING

LAPL’s most recent strategic plan effectively aligns city and library goals. As the library begins a new strategic planning process, Szabo is again drawing on his facilities planning experience in Atlanta: in addition to engaging consultants, “instead of doing a handful of focus groups, or very curated sessions, we went overboard in a wonderful way, with lots of public meetings, lots of opportunities for public input,” he says. When it was time to bring a $275 million bond issue to Atlanta’s voters, he was able to point to specific items in the plan that proved they had paid attention to what people wanted, and it passed.

Szabo has followed a similar model at LAPL, collecting thousands of pieces of community suggestions—up to and including thoughts from toddlers armed with crayons and construction paper. “When you’re genuine in wanting that input, and when you’re genuine in listening, it makes talking about the library, selling it, promoting it, and seeking approval for it from boards, councils, and elected officials, easy, because it’s only saying what the community is saying,” he explains.

Simple advice, perhaps, but it works. Los Angeles has supported its library well. Szabo offers an extra shout-out for the advocacy efforts of the Librarians’ Guild, AFSCME Local 2626, which advocated strongly for Measure L, the Public Library Funding Charter Amendment, in 2011. “All of the things that we have been able to do are due to the voters of L.A. overwhelmingly passing that ballot measure,” he notes. “It has allowed us to be the fabulous library system that I think we are.”

TOWARD COMMUNITY HEALTH

When L.A. Mayor Karen Bass took office two years ago, she declared a state of emergency around homelessness on her first day. She met with all city department heads, and Szabo outlined how the library was already engaged: helping unhoused people find transitional housing, get a meal, or care for a pet they wouldn’t leave behind. “I could have talked for three hours about the things that we’re doing,” he says.

Central Library already offered The Source, a staff-led, one-stop shop to help homeless Angelenos transition to independent and supported living, and to assist low-income residents. But staff alone could not meet the increasing level of needs. Leadership began looking critically at how the library faced those challenges, particularly when it came to security. “We only had one tool in our toolbox, and it often was not the right tool,” says Szabo. “We needed other solutions and other resources.”

He began conversations on the subject with staff in 2018, understanding that they knew firsthand what the issues were and could potentially offer ideas. And they did, with close to 80 recommendations. Those suggestions led to the creation, in 2021, of the Library Experience Office, which houses licensed social workers and representatives from local agencies contracted to provide mental health and social services in LAPL branches. Library Experience Office employees serve as community service ambassadors, trained in de-escalation and able to handle incidents. Library staff also receive trauma-informed training, and more than 500 have learned how to administer Naloxone to reverse opioid overdoses.

“John understands the changing needs of Los Angeles and our communities,” says Supervising Social Worker Edna Osepans, who works with the department’s other employees, contractors, and library staff, making sure they stay safe and encouraging them to prioritize their well-being. “He really listened to staff when they said, ‘We need help—we’re doing social work–related things, and we’re not trained,’ and he advocated for the formation of our department.”

One of Szabo’s earliest partnerships was with United States Citizenship and Immigration Services to develop what were, at the time, called Citizenship Corners. The implication of putting people in a corner didn’t sit well with him, however, so the library rebranded the services as the New Americans Initiative. LAPL began providing one-on-one assistance around immigration and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policies and has locations at seven branches so far.

“When people naturalize, it’s better for economic development, for community health—all good things come from that,” says Szabo. “And it also is about telling L.A. stories, largely because of the population who were born outside of the U.S. Those are immigrant stories, and all that the library can do to lift that up, the better.”

READING FREELY

Szabo thinks back fondly on the library of his youth for reasons beyond the fascinating front desk. He recalls finding books there with gay characters, “and I remember how important and validating that was to me personally, and also what it said about the institution of libraries,” he says. There, in a military base community library, he realized that “there is someone who works here, who gets a paycheck, who made a decision to buy several books with this theme that made their way onto this shelf. That had a big impact on me in terms of loving and wanting to work in libraries, and also understanding what intellectual freedom really meant.”

LAPL’s Read Freely initiative allows anyone in the United States, age 13 and up, to read some of the most challenged ebooks as reported by the American Library Association and, as of last September’s Banned Books Week, travelers passing through Los Angeles International Airport can get a temporary library card to do so. Closer to home, since 2016, every K–12 student in the Los Angeles Unified School District automatically receives a Student Success Card.

|

REASONS TO BE PROUD Top: Szabo and LAPL staff representing the library in the annual L.A. Pride Festival and Parade. Bottom: Szabo congratulates one of the more than 1,000 graduates of LAPL’s Career Online High School program. Photos courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library |

FABULOUS, CREATIVE, AND TALENTED

Moving from Florida’s Palm Harbor to Clearwater library offered Szabo a lesson about placing trust in and empowering staff, he says. “It was the first time I had the experience where my fingertips could not reach to every part of the organization and everything that we did. That was the first time where I had to really trust people to represent what I wanted the institution to be.”

What he’s learned in L.A., he adds, is to prioritize a sense of ownership and potential for staff—“letting them be the fabulous, creative, talented people that they are.” Initiatives range from annual IDEAS mini-grants, in which staff submit ideas to pilot new programs or expand existing services, to supporting staff who want to move up within the organization through the Take the Lead Initiative.

Peña, a 17-year LAPL employee, remembers one of Szabo’s first meetings with managers and staff. “Someone said, ‘We have ideas. We want to do things. Is it okay? Can we do them?’ He said, ‘As long as it’s legal, go for it.’”

“John has made it clear to my boss and to me that it’s okay to make mistakes,” says Osepans. Having social work baked into library services “is all very new—oftentimes, we’re just figuring things out as they happen.”

That enthusiastic buy-in let Peña help Szabo create the L.A. Libros Festival, a citywide Spanish-language book celebration. The idea was spurred by a local literary event held by REFORMA (the National Association to Promote Library & Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish Speaking). “John reached out and said, ‘Madeline, how come we didn’t host it? You know we could do it.’” Now in its sixth year, “it’s our own book festival for Latino Heritage Month,” says Peña, with 5,000 people attending last September. “I get a lot of green lights from John.”

STAFF POWER

Another lesson Szabo points to in leading a system the size of LAPL’s is, ironically, recognizing that it can become insular: “Because we’re so big, we’ve figured it all out—we’ve got an expert here, we’ve got an expert there—so we can be not joiners, not participants elsewhere.”

During his time at the small Robinson Public Library District, he recalls, he didn’t feel a part of the larger statewide or regional community of libraries. Now, “It’s important that big systems like ours turn outward, not only to share what we do and what we have, but truly, genuinely learn from others,” Szabo says. That includes sending staff to conferences, encouraging them to participate in a variety of associations, and empowering everyone throughout the organization to tell the library’s story in different settings, from professional gatherings to the mayor’s office.

“John has always said that we’re not too big to learn from others,” says Peña. “We do great things, but there are a lot of things happening everywhere, and we should be in the conversation. We should be listening to what’s happening in our communities, in other communities, and also learning and sharing from each other.”

“Social workers don’t typically get a spotlight on them. We do our thing in the background—and that’s okay, because it comes with the territory,” says Osepans. “But here at LAPL, our work gets attention. I feel very appreciated, and I think it comes from him. He gives us a lot of credit, and he gives me the power and the freedom to make decisions, which is huge. It’s going to positively impact not only patrons, but staff and the system as a whole. It has this trickle-down effect, coming from him.”

DIGNITY AND RESPECT

“One of the things that has such an impact on me, that I’m just so proud of—that makes me love this profession—is that we treat people with such dignity and respect,” says Szabo. “It’s a service that doesn’t find its way into a brochure or a press release. But the kindness with which we treat people, and that service-oriented approach, is incredibly important.”

When she first came to the library as a commissioner, Cao saw him put those ideals into action when a man who appeared to be unhoused walked into a staff elevator as Szabo was exiting. Rather than hand the man off to a staff member, Szabo asked him where he needed to go, and then walked him over. “John didn’t know that I was watching this,” says Cao. “It was such a simple act of customer service, and it made me realize that he’s not just a manager. He wasn’t going to delegate this to somebody else. He was going to be a frontline customer service helper for this person.”

“John just has the biggest heart of anyone that I’ve ever met,” says Hamilton, “but he’s also one of the smartest people that I’ve ever met, and he’s always looking for ways to serve.”

“The library is lucky to have John F. Szabo,” says Valerie Lynne Shaw, president of the Board of Library Commissioners. “Angelenos love the Library, and they trust John and his staff to provide outstanding service. Thanks to John’s leadership, people rely on the library to help them along their journey and provide lifelong learning.”

Adds Cao, “If you find any of his enemies, I’d like to know what he did. So far I think everyone I know loves him.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!