Novel Collections

Four special holdings that catch the public’s imagination

Reference collections can have a reputation as fusty or mundane, featuring shelves upon shelves of microfiche or huge arrays of maps and letters. While the primary sources preserved in these holdings are tremendously valuable to historians and genealogists, they may not grab the imagination of the general public. Still, every rule has its exceptions—as these four collections illustrate.

At these libraries, researchers can explore items well outside the ordinary, including movie posters that chart the history of Hollywood, tiny tomes that can fit on a fingertip, and even books bound in human skin.

We asked the archivists and librarians who curate these materials to share what makes their collections special.

MEDICAL MISADVENTURES

|

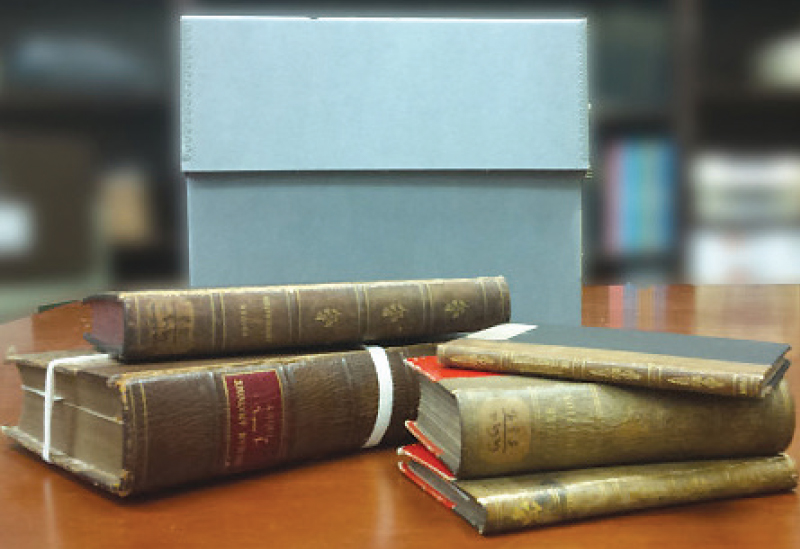

CAREFUL PRESERVATION Bound in human skin, these 19th-century volumes are housed at the Historical Medical Library, part of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia |

The Historical Medical Library’s (HML) history stretches back to 1788, when it was founded as a repository for medical information and other documents of interest to members of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, one of the United States’ oldest medical associations.

While doctors and researchers are regular visitors to the collection, these days pure scientists are usually outnumbered by academics whose research leans toward the liberal arts. “The majority of our researchers work in the broader medical humanities and represent the fields of anthropology, sociology, religion, fine arts, forensics, geography, and linguistics, to name a few,” says Beth Lander, college librarian for HML.

Today, the library works alongside its sister institution, the Mütter Museum, to offer the public a glimpse into their collections and the history of medical developments—and misadventures—they detail.

To Lander’s mind, the most precious items in the library are some of the strangest—and some of the most important to preserve not only carefully but respectfully. Those are the five anthropodermic books in the collection—titles long rumored to be bound in human skin, a fact confirmed by close analysis of the covers in 2015.

“What makes these books truly special is that three of them are bound in thigh skin removed from a 28-year-old Irish immigrant named Mary Lynch, who died at Philadelphia General Hospital in January 1868,” says Lander. “A resident physician there, John Stockton Hough, removed the skin during her autopsy after she died from tuberculosis and encysted trichinosis; tanned it in a chamber pot in the hospital basement using urine; and then held on to the skin until 1887, when he used it to bind three books on women’s health and reproduction.”

Knowing the unique history of these volumes, says Lander, makes her particularly protective of them. Lynch lacked agency over her medical care and the disposition of her body in life, making it all the more important to show respect and care for her remains.

PRESERVING PROPAGANDA

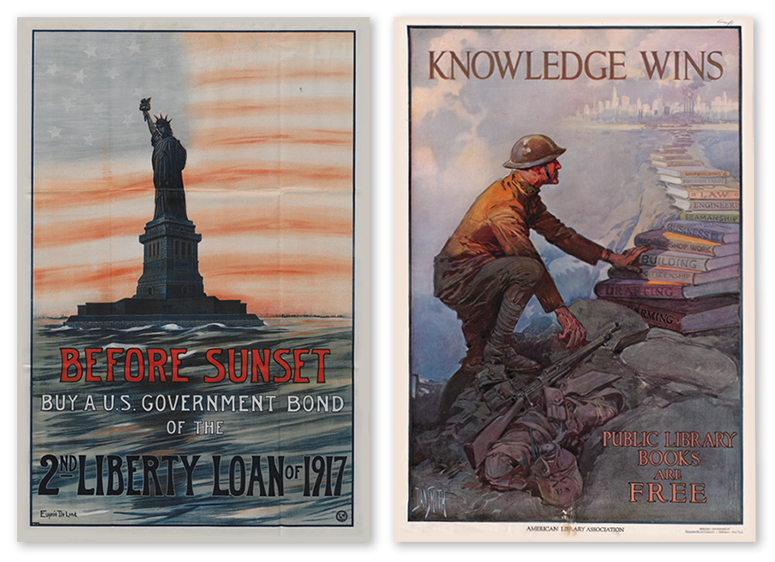

The first seeds of the Propaganda Poster Collection, at Washington State University (WSU), Pullman, were planted during World War I, when the federal government sent numerous posters cheering on the war effort to the school. Once they had served their original purpose, the university’s forward-thinking archivists preserved the pieces following the Great War. In 1937, those pieces were incorporated into the school’s War Library.

While the War Library has since been dissolved, the Propaganda Poster Collection has only continued to grow. Today, the majority of the collection consists of U.S. propaganda posters from World War II, along with a smattering of posters from Russia as well as U.S. posters printed in French and intended for Parisian audiences following the liberation of the city by Allied forces.

Today, manuscripts librarian Cheryl Gunselman oversees the collection, which is now part of WSU’s Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections. Among her favorite pieces is a poster of American children cowering in the shadow of a swastika, exhorting viewers to buy bonds in support of the war effort.

|

DOCUMENTING WARTIME These two selections from Washington State University's Propaganda Poster Collection encouraged citizens to lend their support to World War I |

Maintaining the integrity of these big, colorful artifacts is no small feat; in 2012, the library acquired a large-format overhead scanner to reproduce the pieces digitally. Within a year, the digital preservation project was complete, and the poster collection is now available online for anyone to view.

WSU’s faculty members regularly put the collection to work in their courses, exploring the history of the posters and their relevance more than a century after they first rolled off the presses.

“One of our English instructors has featured these posters in her writing and research classes, asking students to analyze visual rhetoric—imagery, color, font choices—and the textual messages,” Gunselman says. “There are interesting parallels with current use of memes, GIFs, videos, and other types of visual and textual communications intended to persuade.”

TINY TOMES

Indiana University’s (IU) Lilly Library, Bloomington, obtained the bulk of its miniature books collection—16,000 tiny titles—in 1996. Donated by Cleveland schoolteacher Ruth E. Adomeit after her death, these thousands of books represented the fruits of a lifetime Adomeit spent largely traveling the world and collecting books—especially miniature volumes.

Today, the collection mostly attracts the attention of researchers studying niche topics in literary history, such as 19th-century children’s literature and thumb Bibles. That’s not to say the collection doesn’t make an impact on lay readers as well, though, note education and outreach librarian Maureen Maryanski and Sarah McElroy Mitchell, a reading room coordinator and instructional associate at the Lilly Library. “We also think of the permanent display of miniature books in our galleries as one of our greatest crowd-pleasers,” they told LJ.

Readers can explore the digital holdings through the university’s online catalog, IUCAT, or via an online exhibition that features some of the many miniatures on hand. Among the collection’s tiny Bibles and books of nursery rhymes little larger than a fingertip, there are books that are marvels not just of printing and binding but also of engineering. Miniature pop-up books are standouts in the collection, as is a copy of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart that includes a minuscule model of a beating human heart.

For other titles in the collection, size was more than just a gimmick—it was a means of protecting readers and publishers by ensuring that sensitive titles could easily pass under the radar of censors.

“We have a copy of Fruits of Philosophy (1832), the first book printed in the United States to describe birth control methods,” Maryanski and McElroy Mitchell say. “Its small size allowed it to be discreetly passed from physicians to patients.”

|

THINK SMALL Indiana University's Lilly Library holds thousands of miniature books, collected by Cleveland schoolteacher Ruth E. Adomeit |

CINEMATIC HITS AND MISSES

Among its collections, the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center also preserves posters, but instead of political propaganda, these tout generations of cinematic masterpieces. At the physical archives and digital collection, researchers and the curious public alike can view the original advertisements for classics of the silver screen such as To Kill a Mockingbird and Lawrence of Arabia (both 1962). But, says curator of film Steve Wilson, the archives taken as a whole hardly constitute a hit parade. Some of the most fascinating items advertise films that garnered significantly less critical acclaim.

“Our poster collection is particularly rich with the lesser-known ‘B movies’ and drive-in era movies,” Wilson tells LJ. “Some of the surprises were posters for films like I Was a Communist for the FBI, High School Caesar, and Unwed Mother.”

|

B MOVIE BONANZA Offerings from the University of Texas at Austin's Harry Ransom Center, which is home to posters advertising films, both gems and grind house fare |

That lineup hearkens back to the collection’s origins, which began with four separate acquisitions of posters, lobby cards, and other advertising ephemera, starting with a collection from the now defunct Interstate Theatre chain and growing with more recent donations from private collectors and poster dealers.

Wilson and his staff are currently hard at work digitizing the approximately 10,000 posters that comprise the collection, ranging from the silent era to modern movie offerings. While the process of compiling metadata for these pieces (including release dates and performers) is still in progress, Wilson is already looking for ways to expand on it.

“I hope to develop the database in the future to include actors, directors, producers, and studios,” Wilson says. “Probably genre as well.”

Ian Chant is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in Scientific American and Popular Mechanics and on NPR.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!