Organizing the Books in Your Home, Part 2: Getting To Know the Genres

In this second part of this series aimed at helping non-librarians organize the books in their homes, we take a deep dive into genres and subgenres, and offer suggestions on shelving fiction.

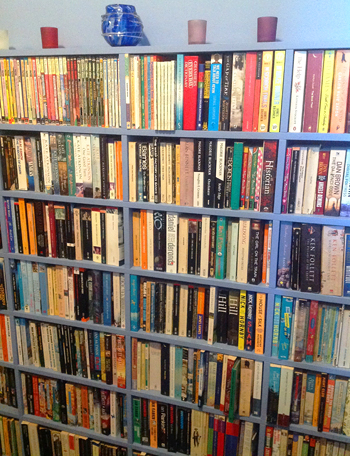

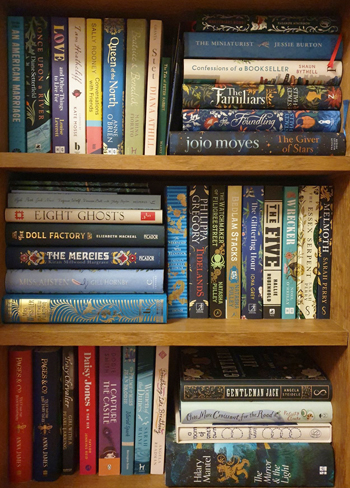

For some readers isolating at home during the pandemic, spring cleaning and home organization have become ways to stay grounded, focus energy, and make the most of ample indoor hours. Readers from around the globe have proudly posted photos of their home collections on social media using the hashtags #ShowUsYourShelves, #ShelfieStyle, and #Shelfie. Book nerds and bibliophiles looking to organize (or reorganize) the books in their homes may find inspiration in the ways librarians think about classification and organize materials in public libraries.

|

Photo courtesy of Twitter user @andover_library |

In the first installment of this series, we looked at the most widely used classification scheme in public libraries, Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC), and how it could be adapted to organize nonfiction, informational books in the home. Though DDC accounts for both nonfiction and fiction—Dewey intended fictional works to be organized under the 800s (Literature) class, further organized by language—the vast majority of public libraries pull most fiction out of strict Dewey classification to make it easier for readers to find the authors and genres they enjoy. (Not to mention the fact that DDC’s 800s class overrepresents Western works, with the 800 to 880s devoted to American, English, Old English, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Latin, and classical Greek works, while only the 890s are focused on “Literatures of other specific languages and language families.”)

ALPHA BY AUTHOR

There are a few main ways most public libraries shelve and display fiction books, the most popular being alphabetically by the last name of the author. So Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice would appear before Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which would appear before Ruth Ware’s The Woman in Cabin 10. For folks with small or medium-size collections of fiction, this could be all you need.

One benefit of shelving all fiction by author is the ease of finding a variety of works by the same author in one place. This can be especially useful when dealing with authors who write across a wide range of genres and formats. Take Neil Gaiman, for example. His work spans from fantasy (Neverwhere) to children’s books (Coraline) to comics and graphic novels (the “Sandman” series). Or consider Margaret Atwood, who has written contemporary realism (Cat’s Eye), historical fiction (Alias Grace), and dystopian sci-fi (The Handmaid’s Tale). Depending on the size of your collection, the shelf space you have available, and the ways you think about and find titles in your collection, shelving simply by the author’s name could be the way to go.

GENREFYING 101

However, for book lovers with many titles in their home and the fortune to have shelf space to display them, breaking up fiction by distinct genres could be useful—and fun! To help you decide which books should go where, the following is a guide to some of the most common and popular fiction genres and subgenres. (This guide focuses mainly on general adult fiction, though much of it could also apply to works for middle grade and young adult readers. Next week, we’ll take a careful look at organizing books for children.)

Most readers will find the major genre categories sufficient, though subgenres can be useful for individuals who own an abundance of titles in a single genre.

Please note that most books fall into more than one genre or subgenre category; part of the challenge (and hopefully enjoyment) of organizing a home fiction collection is deciding which genre or subgenre best represents any given title for your needs.

FANTASY: Speculative fiction defined by a departure from the “real world,” though it can be inspired by and contain elements of known reality. Often includes imaginary scenarios and creatures, magic, supernatural elements, or alternative realities.

- Alternative History: Also called Alt History. A fantastical narrative in which one or more historical events are reimagined. For example, Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell or Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad.

- Anthropomorphic: In which animal or nonhuman characters speak, think, and/or act like human characters, as in Richard Adams’s Watership Down.

- Dark Fantasy: Sometimes called grimdark. A fantastical narrative characterized by dark and scary elements that can cross over into the horror genre. For example, Joe Abercrombie’s The Blade Itself or Anne Bishop’s Daughter of the Blood.

- High or Epic Fantasy: A narrative usually distinguished by the large and epic scope of its world-building. These stories tend to take place in worlds or universes very different from our own, with complex histories, geographies, and cultures. High or epic fantasy stories usually (but not always) feature magical creatures such as wizards and elves. Examples include J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” series and George R.R. Martin’s “Game of Thrones” series.

- Magical Realism: Sometimes called fabulism. Originated in and most associated with stories from Latin America. Narratives are based primarily in realism, often character-driven, with some elements of a magical nature sprinkled in. Examples include Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude, Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits, and Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate.

- Paranormal: Features supernatural creatures such as vampires, werewolves, witches, ghosts, fairies, shapeshifters, and other creatures that fall outside the typical scientific understanding of our natural world. For example, Deborah Harkness’s A Discovery of Witches or Charlaine Harris’s “Sookie Stackhouse” series.

- Retellings: A fantastical retelling of a classic story, often based on fairy tales, folklore, or fables, such as Naomi Novik’s Uprooted and Helen Oyeyemi’s Boy, Snow, Bird.

- Steampunk: Stories in which the fantastical world is built around technology, inventions, or designs inspired by 19th-century industrial (often steam-powered) machinery. Examples include China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station and Bruce Sterling and William Gibson’s The Difference Engine.

- Superheroes: Narratives featuring characters endowed with superpowers, often crime fighters. These works include popular superheroes such as Marvel’s Avengers or DC’s Batman, but can also include books such as Brandon Sanderson’s “The Reckoners” series.

- Urban Fantasy: Fantastical stories set in a city, typically in the present day. They often, but not always, incorporate mystery or noirlike detective elements. Examples include Daniel José Older’s “Bone Street Rumba” series and Ben Aaronovitch’s Rivers of London.

|

Photo courtesy of Twitter user @jamesmparr |

SCIENCE FICTION: Speculative fiction about an imagined future and/or technological advances based on current scientific knowledge, often concerning the impact on humans.

- Aliens: Narratives about extraterrestrial life-forms. These stories can be about first contact, in which humans discover or meet alien intelligence for the first time, invasion, or war narratives; they can also cross over into the space opera genre (see below). Examples include H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, Frank Herbert’s Dune, and Liu Cixin's The Three-Body Problem.

- Apocalyptic/Postapocalyptic: Sometimes called doomsday fiction. Stories about the technological failures and collapse of civilization and the aftermath. For example, Stephen King’s The Stand, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, and Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend. Can sometimes cross over into the dystopian genre (see below).

- Alternative History: Similar to the alt history found in the fantasy genre, these are narratives that reimagine historical events and often extrapolate out alternative futures as a result of that changed history. Examples include Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, and Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Calculating Stars.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI)/Robots: Stories that center on the proliferation of AI and robot technology, often at the expense of human characters or civilization. For example, Isaac Azimov’s I, Robot, William Gibson’s Neuromancer, and Martha Wells’s “Murderbot Diaries” series.

- Cli-Fi: Short for climate fiction. Speculative stories that deal with climate change and global warming, usually extrapolating current climate science predictions and imagining the near or distant future. Examples include Megan Hunter's The End We Start From and L.X. Beckett's Gamechanger.

- Cyberpunk, Biopunk: A type of dystopian sci-fi set in an imagined future, often in cities and urban centers, featuring high-tech advancements (such as AI, robots, or genetic human enhancement) that usually come at the expense of human concerns and/or the social order. Cyberpunk tends to focus on computer technology, whereas biopunk deals with technology relating to biotechnology. Titles include Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, and Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl.

- Dystopian: Similar to and often related to the apocalyptic/postapocalyptic genre, these works usually feature an imagined future in which the rights, concerns, and artistic freedoms of the individual are superseded by technology, tyrannical government, or radical social upheaval. These works tend to serve as allegories and commentaries on the current political or social reality. Examples include George Orwell’s 1984 and Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower.

- Humorous: Any type of sci-fi that exploits and plays with the genre’s conventions for comedic effect. Examples include Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, and Charles Yu’s How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe.

- Low-Fi/Soft-Fi: These tend to be grounded in the “soft sciences” such as anthropology, sociology, or psychology instead of the “hard sciences” of math, physics, or astronomy and reflect humanistic themes. Examples include Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, and Daniel Keyes’s Flowers for Algernon.

- Military: Characterized by a focus on futuristic military technology, often weapons, and how they are used by military organizations, usually during war. Some books in this genre use satire to explore antiwar themes, such as Robert A. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers. Other examples include John Scalzi’s Old Man’s War and Eric Nylund’s Halo: The Fall of Reach.

- Multiverse/Parallel Universe: Fiction based on the premise or exploration of the theory of the multiverse or parallel universes—i.e., the idea that there are alternate worlds or universes beyond the one we know as our unique reality. Many, but not all, of these works include elements of time travel and the idea that traveling into the past can lead to the creation of alternate, sometimes infinite, futures. Titles include Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter’s The Long Earth and Blake Crouch’s Dark Matter.

- Near Future: Stories set in the very near future, usually in a world that looks very much like our own, with some small but significant technological advances. Examples include Dave Eggers’s The Circle and Andy Weir’s The Martian.

- Space Opera: Narratives, often of an epic or melodramatic nature, set in a universe in which space travel into the farthest reaches of the universe is not only possible but the norm. Stories are often plot-driven and feature interplanetary war waged by various alien planets and civilizations, such as Frank Herbert’s Dune, Yoon Ha Lee’s “Machineries of Empire” series, and Becky Chambers’s The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet.

- Thriller/Horror: A work of sci-fi that uses technological advances, alien encounters, or an imagined future to instill fear in the reader; often crosses over into the horror or thriller genres. For example, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, John W. Cambell Jr.’s Who Goes There?, and Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation.

- Time Travel: Stories that explore the possibilities and ramifications of traveling into the past or future. Examples include H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife, and Octavia Butler’s Kindred.

HORROR: Speculative fiction designed to elicit feelings of fear and terror in readers, often serving as metaphor and/or commentary on contemporary social or political concerns.

- Animals and Killer Creatures: Stories featuring fearsome creatures either real or imagined. Examples include Peter Benchley’s Jaws, Stephen King’s Cujo, and Hunter Shea’s The Montauk Monster.

- Crime/Serial Killer: Narratives that combine elements of crime fiction—detective stories, police procedurals, mysteries—with dark elements designed to terrorize, sometimes presented from the perspective of the killer and/or with a focus on gory details. Titles include Stephen King’s The Outsider, Robert Bloch’s Psycho, and Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs.

- Domestic: Often crossing over into the psychological horror and/or the psychological thriller/suspense subgenres, these are books that focus on crimes and terrors that take place within the home, often among family members. Examples include Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw and Victor LaValle’s The Changeling.

- Gothic: Works of horror defined by dark, atmospheric, even romantic settings, often taking place in large manor houses or mansions, with melodramatic plots in which humanity or human protagonists (or antiheroes) go up against supernatural forces of evil—and typically lose. Examples include Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle.

- Hauntings/Ghosts: Fiction centering on haunted places, houses, or people and/or ghosts and ghostly appearances. These works often overlap with gothic horror. Titles include Edgar Allan Poe’s short story "The Fall of the House of Usher," Richard Matheson’s Hell House, and Joe Hill’s Heart-Shaped Box.

- Occult/Religious: Works dealing with witchcraft, Satanism, spiritualism, psychic phenomena, demonic possession, and other mystic and arcane phenomena. Examples include William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist and Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby.

- Psychological: Fiction in which the protagonist endures mental and emotional stress triggered by real or imagined terrors. These works tend to overlap with psychological thrillers. Examples include Marisha Pessl’s Night Film, V.C. Andrews’s Flowers in the Attic, and Cormac McCarthy’s Outer Dark.

- Slasher: This type of horror usually features characters being tortured and murdered by a psychopathic killer. Some modern takes on this subgenre smartly play with and upend traditional tropes. Though this subgenre is more commonly found in film rather than prose, some examples include Jack Ketchum’s The Girl Next Door, Stephanie Perkins’s There’s Someone Inside Your House, and Riley Sager’s Final Girls.

- Supernatural: Fiction that centers on witches, vampires, werewolves, demons, ghosts, or other supernatural creatures. Examples include Anne Rice’s “Vampire Chronicles,” Stephen King’s It, and Nora Roberts’s The Hollow.

- Weird: Also known as weird fiction, it often combines elements of horror, fantasy, and sci-fi. It is marked by the sense that something dark and unsettling underlies the main narrative, usually with surreal, nightmarish elements. Examples include Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves and Chuck Palahniuk’s Invisible Monsters.

ROMANCE: A narrative centering on a love story that concludes with an emotionally satisfying, optimistic ending, aka a “happily ever after.”

- Contemporary: A romance set in the present day. Examples include Helen Hoang’s The Kiss Quotient and Alyssa Cole’s A Princess in Theory.

- Erotic: Stories about the development of a romantic relationship in which sex is an inherent part of the plot and character growth, distinct from erotica (see below). Examples include E.L. James’s The Mister, Tibby Armstrong’s Surrender the Dark, and Parker Swift’s Royal Affair.

- Historical: A romance set any time in the past. Some of the most popular historical romances take place in the Regency, Georgian, and Victorian periods. Examples include Beverly Jenkins’s Rebel, Grace Burrowes’s A Duke by Any Other Name, and Joanna Shupe’s The Prince of Broadway.

- Inspirational/Religious: Most often Christian-themed, this subgenre usually features the leads finding connection through their shared faith. Examples include Francine Rivers’s Redeeming Love, Karen Witemeyer’s Short-Straw Bride, and Beverly Lewis’s “Seasons of Grace” series.

- Paranormal: Romance that incorporates elements of fantasy, often featuring magic or supernatural creatures. Titles include Jenn Burke’s The Dragon CEO’s Assistant, Nalini Singh’s Wolf Rain, and Christine Feehan’s Bound Together.

- Romantic Suspense/Thriller: Romance in which a suspenseful element is integral to the plot. Examples include J.R. Ward’s Consumed and Christina Dodd’s Dead Girl Running.

|

Photo courtesy of Twitter user @busybookshelves |

MYSTERY: Narratives that focus on solving a crime.

- Cozy: Characterized by a lack of violence and sexual content. They often take place in small, quaint communities; feature amateur sleuths; and tend to include humorous elements. Examples include Joanne Fluke’s Chocolate Chip Cookie Murder, M.C. Beaton’s The Quiche of Death, and Lillian Jackson Braun’s The Cat Who Could Read Backwards.

- Detective/Sleuth: In which the main character is a detective or private eye investigating a crime. Examples include Agatha Christie’s “Hercule Poirot” books, Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Sherlock Holmes” novels, and Sue Grafton’s “Kinsey Millhone Alphabet” series.

- Historical: A mystery set in the past. Examples include Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, Ellis Peters’s A Morbid Taste for Bones, and Tess Gerritsen’s The Bone Garden.

- Medical: Often set in a hospital or health-care facility and starring medical professionals, these mysteries revolve around unknown diseases, conditions, or poisonings. Titles include Robin Cook’s Coma and Michael Crichton’s The Andromeda Strain.

- Noir: Often associated with hard-boiled detective stories, this subgenre is marked by darkness in theme and subject matter, in which there are no clear definitions of right and wrong. They are often set in grim, urban places featuring an antihero with a nihilistic worldview. Examples include Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, Walter Mosley’s Devil in a Blue Dress, and Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon.

- Police Procedural: A mystery in which the focus is on the investigative process, often from the viewpoint of the lead investigator or department. Examples include Jo Nesbø’s Police, Louise Penny’s Still Life, and C.J. Box’s The Disappeared.

THRILLERS/SUSPENSE: Books that elicit feelings of dread, excitement, and/or anxiety, often featuring a villain whom the protagonist must uncover and/or survive.

- Domestic: Often overlaps with the psychological subgenre; these narratives often center on interpersonal relationships and typically feature "ordinary" people doing very bad things. Titles include B.A Paris’s Behind Closed Doors, Lisa Jewell’s The Family Upstairs, and Liane Moriarty’s Big Little Lies.

- Eco-Thriller: Also called Environmental Thrillers. The plots revolve around a current or pending environmental disaster on a global scale. Examples include Lincoln Child’s Terminal Freeze, Neal Stephenson’s Zodiac, and James Patterson’s Zoo.

- Legal: Typically follows lawyers or legal professionals as they solve a crime or right a legal wrong. The intricacies of the justice system usually play a large role in these stories. Examples include John Grisham’s The Firm, Scott Turow’s Presumed Innocent, and John Lescroart’s Hard Evidence.

- Political: A thriller about political struggles or machinations, scenarios, and/or scandals. Examples include Richard Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate and Bill Clinton and James Patterson’s The President Is Missing.

- Psychological: Stories that incorporate elements of mystery, usually featuring a protagonist experiencing a high degree of emotional and mental anxiety. Titles include Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, S.J. Watson’s Before I Go To Sleep, and Ruth Ware’s The Turn of the Key.

- Spy/Espionage: Sometimes, but not always, related to the political subgenre, these stories center on espionage and governmental or organized subterfuge. Examples include John le Carré’s The Man Who Came in from the Cold and Robert Ludlum’s “Bourne” series.

- Techno-Thriller: Stories that revolve around technology, hacking, advanced weaponry, or other machines, usually involving the military. Titles include Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six and Dan Brown’s Digital Fortress.

ACTION-ADVENTURE: Plot-oriented narratives grounded in realism in which characters must survive dangerous situations or environments.

- Expedition/Treasure Hunt: Stories typically featuring an explorer, academic, or professional treasure hunter searching for booty, fame, or glory. Examples include Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, Douglas Preston’s The Codex, and James Rollins’s Sandstorm.

- Disaster: Centers on a realistic natural or human-made disaster that the protagonist(s) must survive using skill, strength, or smarts, such as Harry Turtledove’s Eruption.

- Heist: In which a group of people attempt to steal something, à la Ocean's 11. Examples include Donald E. Westlake’s The Hot Rock and Pamela Q. Fernandes’s The Milanese Stars.

- Military: Stories involving war or battles. Examples include Brad Taylor’s Hunter Killer and Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October.

- Western: Stories set in the American “Old West” during the latter half of the 19th century. Examples include Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, Louis L’Amour’s “Sacketts” series, and Joseph M. Marshall III’s Hundred in the Hand.

- Wilderness/Survival: Stories in which the protagonist must brave the perils of the great outdoors to survive. Titles include Diane Les Becquets’s Breaking Wild and Beth Lewis’s The Wolf Road.

HISTORICAL FICTION: Narratives set in the past that are loosely based on historical fact. Subgenres of historical fiction are typically based on era or time period. Examples include Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall, Elena Ferrante's "Neopolitan Novels," and Ken Follett's The Pillars of the Earth.

EROTICA: Distinct from erotic romance (see above), these narratives are designed to arouse sexual desire.

There are bound to be books that don’t fall neatly into any of the above genres. Many public libraries solve this problem by having a general fiction collection. Simply putting all outliers into a final, broad category may work for titles that do not fit elsewhere.

Others may want to consider additional categories, including contemporary fiction, which is generally any book set in the modern era that may not conform to the above popular genres, or literary fiction, which some readers believe is distinct from genre fiction by virtue of its literary merit.

Book lovers should note that additional categories may include types of books that share a format, rather than a genre. These include graphic novels/comics and short stories. These format categories may include any of the above genres.

Once you decide which genres, if any, you’d like to display in your home collection, shelve the books within that genre/subgenre section alphabetically by the last name of the author, keeping series titles together in the order in which they were published.

Thinking about or in the process of organizing your home library? Ask the librarian for advice or share your progress.

This article appeared in the Your Home Librarian special newsletter. Subscribe here.

Kiera Parrott is a librarian and the reviews & production director for Library Journal and School Library Journal.

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing