Payday | LJ Salary Survey 2014

For many, salary discussion is the last taboo. But without knowing how their peers are compensated, it can be hard for librarians to make their case for better pay—and hard for library leaders to make the case to funders that higher salaries are necessary to attract and retain the best candidates. Even in public institutions, where salaries are often a matter of public record, figuring out who in another institution is the right apples-to-apples comparison for benchmarking can be a challenge.

For many, salary discussion is the last taboo. But without knowing how their peers are compensated, it can be hard for librarians to make their case for better pay—and hard for library leaders to make the case to funders that higher salaries are necessary to attract and retain the best candidates. Even in public institutions, where salaries are often a matter of public record, figuring out who in another institution is the right apples-to-apples comparison for benchmarking can be a challenge.

There is some information already out there. The American Library Association (ALA) did a salary survey in 2008; its Allied Professional Association provides a database through 2011; and the U.S. Department of Labor shares some data but doesn’t get very granular in terms of specialty or title. There are cross-field crowdsourced sites like Payscale (the source of the numbers underlying Forbes’s controversial contention that the MLIS is the country’s worst graduate degree). LJ has, for years, conducted its annual Placements & Salaries survey (see “The Emerging Databrarian,” LJ 10/15/13, p. 26–33), which focuses on recent Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS and equivalent degree) graduates, to dig into what beginning librarians earn in their first positions and what trends those salaries reveal about the field as a whole. Now, with the help of more than 3,200 public, academic, school, special, government, and consortium librarians from all 50 states, we take a deeper look at the range of the field’s salary potential.

It’s not possible to provide an exact match to the unique set of circumstances each librarian brings to the negotiating table—the educational qualifications, the job responsibilities, the years of service, the size of the system, and the regional context all combine in too many different ways.

Nonetheless, LJ’s inaugural salary survey for U.S. librarians and paralibrarians will help readers get closer to understanding how their salary compares with those of their peers.

Click here to view all tables below as data instead of images (link will open in a new window)

(click image to view table as data)

The top line

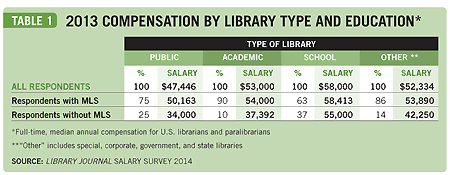

The responses revealed some intriguing trends. School librarians took home the highest median salary ($58,000), public librarians the lowest ($47,446), with academic and other librarians falling in between.

Two-thirds of librarians reported receiving a pay increase in 2013, though not a very big one: they averaged 2.7% (median 1.5%). Some 33% received their increases owing to cost of living adjustments (COLA); 20%, merit pay raises; 18%, longevity increases (common to schools); and 9%, new jobs.

This just beat the COLA: the official COLA for 2013 was 1.7%, though librarians who attributed their increase to COLA received 2.2%.

Consistent with earnings stagnation nationwide, however, over a quarter of librarians (28%) did not receive any pay increase in 2013, and 5% reported that their earnings actually dropped, a development they attributed to higher insurance costs, reduced hours, furloughs, and changing jobs.

Education counts

In the academic and public arenas, holding an MLIS made a major difference to compensation. Those holding MLS degrees made nearly 50% more than those working in academic or public libraries without an MLS. This debunks the skepticism expressed by a number of respondents about the worth of the degree—one even wrote, “If anyone said to me that they were thinking of getting an MLIS, I would do everything in my power to convince them not to.”

In the K-12 setting, however, earnings for those without a library science degree approached the same amount of those with one, perhaps because many of those without an MLIS held other advanced degrees.

Three-quarters (78%) of all full-time respondents reported having an MLIS degree, with another 3% currently working toward one. A third of public and academic libraries (34% and 31%, respectively) provide tuition reimbursement for library school. Less than a quarter of school library and special library employees receive that perk.

(click image to view table as data)

Can’t get no satisfaction?

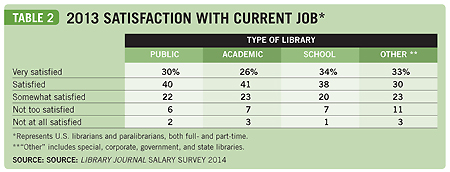

Nearly one third of respondents (31%) were “very satisfied” with their jobs in 2013. Academic librarians’ were slightly less content: 26% reported being “very satisfied.” Part-time status correlated with lower satisfaction: overall, only 23% of part-timers reported being “very satisfied,” compared with 32% of full-timers.

Though one might assume stagnant pay would drive dissatisfaction, lack of recognition and problems with management outpaced low salary. “Some managers are risk-averse and are not willing to try innovative ideas. Upper management does not communicate directly with staff,” noted one Texas public librarian.

Said another respondent, “Our top administrators do not understand the training and knowledge we have, nor do they allow us any opportunities to explain or demonstrate them.” Little or no advancement opportunities and increased workloads also weigh on satisfaction.

Barely 27% of librarians feel they have opportunity for advancement in their position (a number that’s stable across full-time and part-time employees). That doesn’t mean their jobs don’t change: nearly three-quarters (71%) said their responsibilities have changed in the last three years, owing primarily to new technology, downsizing of staff, fresh program initiatives, and their own gumption. Downsizing takes its toll even on the survivors: only 62% of full-time and 46% of part-time librarians feel soundly secure in their positions, while 11% of part-timers feel downright insecure.

(click image to view table as data)

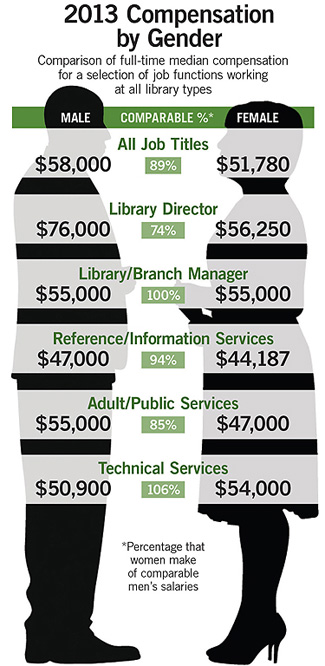

Gender still matters

About 10% of all survey responses came from men, who mostly work in academic and public libraries providing managerial and information/public services. In this female-dominated field, women librarians make roughly 89% of what their male counterparts earn. The difference in salaries between male and female directors is more striking, with women directors making only about 74% of comparable men’s salaries. Among library managers, we found no difference between male and female median salaries. In technical services, women actually make 6% more than men do.

One respondent attributed the whole profession’s low rate of pay to gender norms, explaining, “Our profession suffers from gender bias; it’s academic work and demanding work, but it’s women’s work, and women are trained to not ask for fair reimbursement.”

Please note that in the initial fielding of the survey, LJ did not offer transgender-inclusive options and so did not receive enough responses from librarians who identify as a gender other than male or female to draw statistically meaningful conclusions. More inclusive options were added to the survey before it closed, in response to community feedback, and they will be present in all future LJ research. We apologize for the oversight.

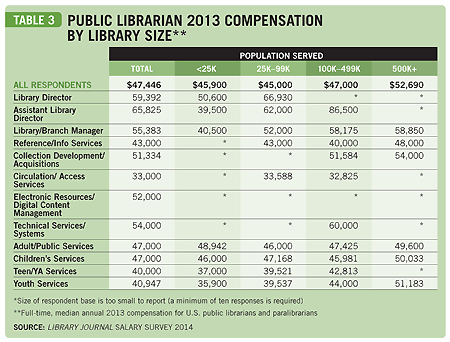

Public librarians

Among all full-time public librarians surveyed, the median 2013 income was $47,446. Salaries for library directors ranged from $20,000 to $310,000, with the median registering at $59,000, tempered by an abundance of responses from directors serving small populations. Interestingly, assistant public library directors beat out their bosses when it came to median salary, likely because the smallest districts don’t have this position—they recorded the highest median of almost $66,000 (salaries ranged from $26,000 to $110,000). Others to garner the highest wages in public libraries were branch managers (median: $55,000), technical services (median: $54,000), electronic resources (median: $52,000), and collection development librarians (median: $51,000). Circulation staff (median: $33,000) and YA/teen services (median: $40,000) were the lowest earners.

Public library compensation generally increases with the size of the library system. The prevalence of public library employees with an MLIS degree also increased with population served (64% of respondents in libraries serving fewer than 25,000 have an MLIS, compared to 89% of library staff serving 500,000+). One factor in play here: nearly half of the largest library systems provide tuition reimbursement for library school, compared to less than a quarter of libraries serving populations under 25,000.

(click image to view table as data)

Pay increases at public libraries averaged 2.9% in 2013, with 27% reporting no pay raise at all. Outreach librarians and electronic resources personnel recorded the highest increases, over 4%. Library directors and children’s services raises averaged 3.5% to 3.9%. More than one-third of public librarians (38%) believe there is opportunity for advancement in their position (the best prospects over all library types), and, indeed, 6% did receive a promotion in 2013.

Thirty percent of public librarians overall are “very satisfied” with their jobs. Despite their comparatively lower salaries and tuition reimbursement, job satisfaction peaks at smaller libraries serving populations of 25,000 or less, where 36% were “very satisfied” with their jobs. There was no measurable difference between job satisfaction for public librarians with an MLIS versus those without, but part-time status did seem to impact satisfaction negatively (25% “very satisfied”). The top cause of public library job dissatisfaction is lack of advancement opportunities, followed by low salary and lack of recognition.

Where have all the full-time jobs gone?

Given the lower job security and satisfaction that comes with part-time status, increased hiring of part-timers by public libraries is distressing. Sixteen percent of all public librarians responding to this survey held part-time positions (compared to only 6% of academic and school librarians working part-time). The public library departments with the highest percentage of part-time workers were circulation (26%) and reference (23%).

“Our library hired on about a dozen new people—but all of them are part-time, less than 20 hours per week, and get no benefits. That seems to be the trend—the Walmart-ization of the workforce,” wrote a circulation head in North Carolina. “I’m hiring folks with MLSs for part-time temporary work. They are desperate to work in a library and cannot find a job.”

Many respondents echoed this perspective from the other side of the hiring desk, particularly from public libraries, saying their systems require years of part-time work from credentialed librarians before even considering them for full-time positions. Said one, “This can include a number of years but the gut-wrenchingly low pay leaves you feeling inadequate and unappreciated.” Another asked, “Are there a lot of other professions that require a master’s degree for part-time work? And full-time positions are given to nonlibrarians frequently so libraries don’t have to pay the higher salary an MLIS demands.”

Our survey found that 50% of part-timers currently have an MLIS and another 11% are studying for one.

(click image to view table as data)

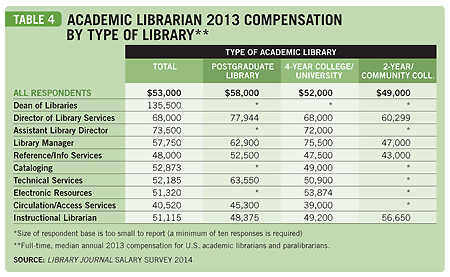

Academic librarians

Full-time academic librarians in our survey made a median of $53,000 in 2013. Salaries in postgraduate department libraries came in nine percent higher and in community college libraries, eight percent lower. The academic library job titles pulling in the highest wages were dean of libraries (median: $135,500), assistant library director (median: $73,500), collection development staff (median: $69,700), and director of library services (median: $68,000). The lowest median salaries belonged to acquisitions and circulation/access services personnel, both at $40,500.

Two-thirds of academic librarians received a salary increase averaging 3.4% in 2013. Digital content management pay increased the most at an average of 8.2%, with e-resources earnings also high at 6.6%. Though most increases were COLA or merit pay raises, 9% of respondents indicated their increase was the result of a new job.

We asked how satisfied academic librarians were with their jobs, and a quarter (26%) replied “very satisfied.” Community college librarians logged the lowest “very satisfied” percentage (16%). Dissatisfaction in academic libraries is most often tied to lack of advancement opportunities, followed by low salary and problems with management. (“The position I was hired to work 15 years ago is the position I’ll probably retire from 26 years from now,” said one academic librarian.) Positive drivers of satisfaction mentioned in the comments included nine- or ten-month contracts and the opportunity to take sabbaticals.

Academic librarians are the most likely to feel secure in their current position, with 24% feeling “very secure.” This very well could be tied to tenure—17% of respondents currently have tenure and another ten percent are on a tenure track. Tenure makes a big difference to the bottom line: librarians with tenure make a median of $72,750 versus $49,596 for those without tenure.

For many academic librarians, especially at the undergraduate level, tenure is not an option. In lieu of tenure, many mentioned they have faculty status or continuing appointment, providing some of the advantages of tenure.

For those who are on the tenure track, with tenure comes the stress of the publish-or-perish culture. “I feel that being on tenure track detracts from being better at my actual job,” an Indiana cataloging librarian wrote.

An instructional librarian weighs her non–tenure track faculty position this way: “My position pays less than other similar positions, but the campus climate is very good, it’s low stress, and I have a lot of academic freedom, so it seems like an OK trade.”

Academic librarians working in the Mid-Atlantic region recorded the highest annual salaries (median: $61,500), while those in the South, making less than $50,000 per year, had the lowest.

(click image to view table as data)

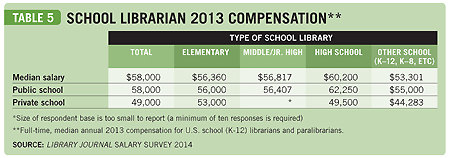

School librarians

Librarians serving K–12 in our study had a median full-time salary of $58,000 in 2013, higher than the public, academic, or other library sectors. High school librarians earned 7%–9% more than those serving lower grades. Nearly all school librarians responding (94%) were full-time employees. However, as has been widely reported, all is not as rosy in school libraries as these numbers may make it sound: the total number of school librarians is decreasing more than other school staff, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Common Core Standards are adding new responsibilities, and many respondents echoed the plaint of one school library media specialist who said, “There used to be three people doing my job. Now it is just me.”

While fewer school libraries seem to be turning to part-timers, perhaps because of collective bargaining, an increasing number of schools have hired paralibrarians, as evidenced by 37% of our school library respondents not holding an MLIS degree. However, these school library workers often have education degrees, if not the MLIS (84% held at least one advanced degree). We found that having an MLIS only slightly improves compensation for school librarians, an increase of roughly $6,000.

Public school librarians had a median 2013 compensation of $58,000, 18% higher than those working at private schools. Regionally, compensation for school librarians in the Mid-Atlantic spiked at $74,000. Librarians there have logged the longest time in their positions, but whether this is a cause or effect is unclear.

(click image to view table as data)

The average school librarian’s pay raise in 2013 was 1.8%, the lowest for all library types. One-in-three (29%) received no raise, and 7% reported that their pay actually decreased, primarily due to escalating employee benefit contributions. Only 9% feel they have opportunity for advancement.

Nonetheless, school librarians have the highest job satisfaction levels. One third (34%) were “very satisfied” with their current job. For those who declared dissatisfaction (8%), nearly twice as many attributed their troubled feelings to increased workloads and lack of recognition as to low salary.

Twelve percent of respondents sustain library services at more than one school. These librarians make a median annual salary of $60,000, $3,000 more than those working in one school. “It is frustrating to not have enough hours (and pay) for what I do, but I love my job,” explained one elementary paralibrarian from Washington State.

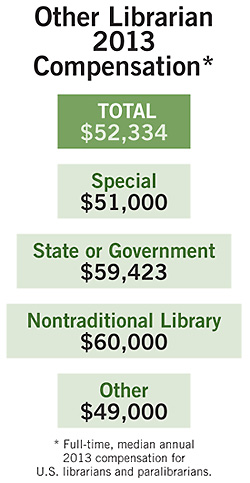

Special librarians

A final group of respondents work in specialized libraries (including corporate, medical, museum, prison, state/government libraries, or library cooperatives) or apply their skills outside of a traditional library setting, working for library vendors, doing digital asset management in a corporate setting, or teaching in library school. As one consortium librarian put it, “We need to take advantage of all the parallel careers out there.”

The aggregate median full-time 2013 salary for this cohort was $52,334. Their average pay increase was 3.7% in 2013. While one-third (33%) were “very satisfied” with their jobs, another 13% indicated dissatisfaction, higher than for any other type of library. Lack of recognition and problems with management are common sources of dissatisfaction among them.

Money isn’t everything

In spite of all the challenges they face, it is telling that librarians’ comments to this survey most frequently began with, “I love my job,” even if it was usually some form of “I love my job, but....”

While librarians need, and deserve, to be paid as professionals for their increasingly complex labors, one thing that stands out in the responses to this survey is that raises per se aren’t what most librarians want most. Several other things would go a long way to increasing job satisfaction: full-time jobs, with benefits; security in the positions they have now and the chance to grow within the organization; nonmonetary recognition for all that they do; better relationships with their library’s management; and an end to increased workloads (or at least some help in handling them). Increased flexibility in job requirements could help increase satisfaction in the field in general: several librarians cited frustration with silos, which make it difficult to switch among library types.

Of course, providing some of those things would also cost too much money for cash-strapped systems still recovering from recession-driven funding cuts. But recognition, at least, is free, and such intangible benefits can make all the difference to improving morale and preventing burnout. As one commenter put it, “While the pay is not great, the working environment—library staff, students, faculty—is fantastic!”

METHODOLOGY & BACKGROUND

The LJ salary survey for U.S. librarians and paralibrarians was emailed to LJ and School Library Journal e-newsletter subscribers in March 2014. The survey link was also broadcast via LJ’s Facebook and Twitter channels. Results were tabulated in-house based on 3,210 total respondents.

Please note that salaries reported here represent median 2013 compensation for full-time library employees. Hourly employees, representing 16% of full-time employees, reported their 2013 compensation in aggregate for the year.

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing