Intersectional Accessibility: Creating Inclusive Spaces, Examining Ebook Accessibility

Libraries are incorporating collaboration, creativity, and a steadfast commitment to create accessible and inclusive spaces. Also, LJ looks at EBSCO's academic ebook accessibility findings.

Libraries are incorporating collaboration, creativity, and a steadfast commitment to create accessible and inclusive spaces

Libraries have been leaders in accessibility for hundreds of years, producing print materials for the blind in the 1800s, pushing back against so-called “ugly laws” intended to keep people with disabilities out of community spaces in the 1900s, incorporating adaptive technology in the 1920s, and developing and promoting standards for equal access in the 1960s. Recognizing that accessibility is something that happens with and for the people served is part of what it means to create and maintain inclusive service.

Alicia Deal, public services librarian at Dallas Public Library’s J. Erik Jonsson Central Library, feels this process requires cultivating “an environment that authentically caters to the diverse needs of the community through collaboration, creativity, and a steadfast commitment to ongoing learning.” Access needs are not universal, and neither are the ways to meet them.

As a disabled and d/Deaf librarian, Deal has experienced this from multiple angles. “It’s important to acknowledge that disabled individuals may not always be immediately aware of their needs,” she notes. “Many, including myself, have spent a significant portion of their lives without the necessary support and accommodations. As technology evolves, the disabled community continues to explore and understand what we need to fully participate in society.”

“This underscores the significance of incorporating universal design principles when developing services and programs,” Deal continues. “Universal design helps address the evolving needs of the disabled community and eases the process of seeking assistance, particularly for those less adept at self-advocacy.”

Access needs are more complex than disability alone, intersecting with class, race, culture, age, geography, gender, and identity. One successful example is the Connect Crew Outreach Team, created by Memphis Public Library (MPL), which provides programming to underserved communities and individuals. “Memphis is a city with economic and transportation challenges, including higher than average poverty rates and fewer cars per household than our peer cities, and we realize those who need us most may not have access to traditional library services,” explains MPL Assistant Director Jamie Griffin.

Brent Greyson, instructional design and accessibility specialist, Oklahoma ABLE Tech, at Oklahoma State University Department of Wellness, emphasizes the need for awareness as well as access. “I think the need for accessibility work is growing every day. It’s always been a bigger need than many realize, but the rise in chronically ill and disabled people since COVID is staggering,” he says. “I think aside from resources, general awareness is also a hurdle that we’re trying hard to overcome. Even though almost all of us will be disabled at some point in our lives, many don’t think about it until it happens to them or someone they know.”

|

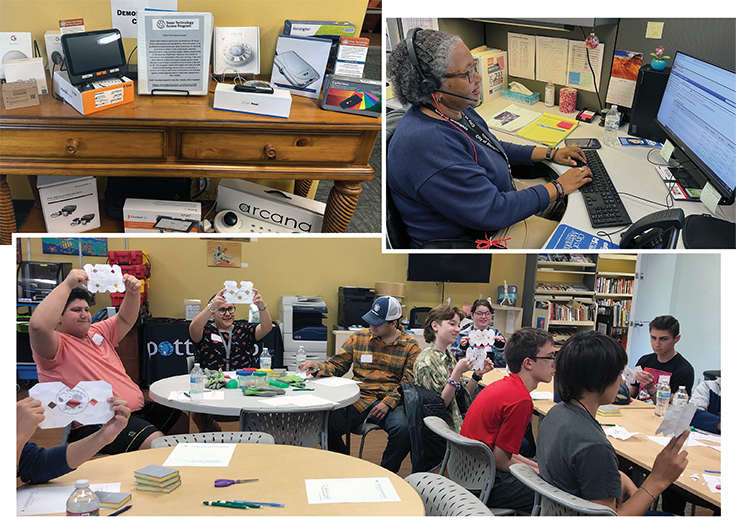

ACCESS FROM MANY ANGLES (top l.) Table with assistive technology devices on display, including magnifier, OrCam Read, smart light bulbs, and pill dispenser; (top r.) LINC 2-1-1 staff member at Memphis Public Library helping a community member with wraparound services over the phone; (bottom) part of the training for Pottsboro Library’s Intergenerational Digital Navigator Simulation Lab, where teens experienced trying to interpret unfamiliar written instructions. |

CREATING ACCESSIBLE SPACES

Creating or improving access can be expensive, complex, and overwhelming. Figuring out where to start, what to focus on, or who to ask can lead to contradictory or confusing answers. There may be a limited budget, small staff, or conflicting needs, such as in the case of COVID-19 precautions.

“For d/Deaf people, COVID is a nightmare,” says KayCee Choi, branch manager at Dallas Public Library’s Grauwyler Park Branch. “I and a lot of hard-of-hearing and d/Deaf people read lips. With the need for masks, the world becomes ‘silent.’” Choi purchased visors for her staff so that they are protected from forehead to collar, but their faces are also still completely visible. Plexiglass barriers can block or muffle sounds and create a glare, so she uses a Teltex GLT captioning device with an omnidirectional microphone at the service desk, which picks up sound and captions speech in real time using Google’s Live Transcribe app, developed in partnership with Gallaudet University. “It’s not 100 percent perfect,” says Choi, “but with lipreading and this device, I can pretty much understand just about any customer.”

Making a library more accessible can look like a large retrofit, but small, focused additions based on community asks, or even accessing free training to increase awareness and gain tools to better work in solidarity, can cover a range of accessibility goals. For libraries looking to get started, Project Enable is a program focused on training library professionals to enhance accessibility and equity within libraries.

Last year, North Carolina State University Libraries completed a redesign of staff work areas to include adjustable-height work surfaces and highly adjustable lighting, the inclusion of freely available wheelchairs in clear view at all public entrances, and the creation of sensory maps highlighting spaces that are quiet or uncrowded, or that have natural or warm lighting. (See “An Ethical Imperative”: Expanding Accessibility in Libraries at NC State.)

“Some users may find it difficult or overstimulating to study in noisy areas; some find crowded spaces distracting or distressing; and some may find bright overhead lighting annoying, uncomfortable, or even the cause of migraines,” explains Robin Davis, associate head of user experience. Facets of the map have also been incorporated into their online space finder, Explore Spaces.

Pottsboro Library, TX, added durable medical equipment to its Library of Things, including a wheelchair, walker, and, through an American Heart Association partnership, blood pressure kits. When a patron requested help with reading his bills, it acquired a large magnifier that he uses to read his mail. The library’s digital navigators (DN) are trusted guides who offer community members ongoing assistance in internet adoption services, including affordable internet access, device acquisition, technical skills, and application support. While the intergenerational arm of the DN program ended when its grant funding ran out, Pottsboro Director Dianne Connery says they hope to be first in line when Digital Equity Act funding becomes available.

Pottsboro Disability Coordinator Renee Nichols also highlights the library’s work around digital accessibility. Its programs and services evolve as new opportunities and community needs reveal themselves, with a focus on achieving digital equity. The library has been heavily involved in all aspects of digital inclusion work. “Digital equity is a super social determinant of health,” she says. “Any problem a person has is made worse if they are not connected.”

Choi suggests evaluating a library’s space to find ways to expand access that can be simple, but very impactful. For example, she says, “Wider doors and aisles. Mobility devices need all the space in the world to get people through and around. Congested shelving or shelves that weave around may look aesthetically cool but are a nightmare for wheelchairs and scooters to maneuver through.”

Connecting with your state, territory, or district’s AT (Assistive Technology) Act Program Center could also improve accessibility affordably, with resources ranging from information to financial assistance. Greyson, a former librarian, is excited about a Library Kit under development for Oklahoma Libraries. “We hope it can also be used as a model in other regions,” he says. “For libraries with fewer resources, we will provide some of the 3-D-printable AT used for demonstration purposes, and when their patrons contact us, we can get them their own 3-D-printed AT, often at no charge!” Examples include a key holder, a palm pen holder, and a guide that helps people write their signature in a straight line.

BRINGING THE LIBRARY TO THE COMMUNITY

There are many people and communities who have a challenging time accessing library resources and spaces, and many libraries with limited space, staff, or budget to provide the programming that’s needed. Solutions that libraries have discovered through responding to the pandemic, climate change disasters, and community challenges can become part of the network of services and practices that expand access and the ability to participate.

MPL has developed multiple programs in response to local needs and emergencies, including its LINC 2-1-1 department, which serves more than 60,000 people each year. The service employs two full-time social workers who provide case management, and staff who assist callers in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Benefits enrollment and other wraparound services. The library also partners with local agencies and community-based organizations to provide regular legal clinics, food distribution, and direct services for seniors. Its curbside service and mobile computer lab increase access for people with mobility issues and those who are high risk for COVID. Outreach teams went to approximately 180 different locations across the city in 2023.

“MPL has worked tirelessly to improve equitable access to services, provide educational opportunities for all ages and learning levels, and to meet the diverse needs of the community,” explains Griffin. “This means we must continuously evaluate and improve accessibility measures and understand that there is no finish line with this work.”

While services like these are incredibly important, outreach doesn’t have to involve extensive programming or large budgets to make an impact. “I actively engage with disabled individuals and seek partnerships with local disability advocacy organizations,” says Deal. “This collaborative approach ensures that my program planning is informed by the lived experiences and needs of the community, thus promoting a sense of ownership and shared responsibility.”

Pottsboro Library offers hybrid programming and meetings for people who cannot visit in person; using a Meeting OWL (owllabs.com) allows remote participants to be part of the experience. It hosts regular community conversations where residents, county businesses, local government officials, nonprofits, mental health services, and other stakeholders are invited to talk about the library and the community. Pottsboro also participated in a pilot program through Texas State University’s Translational Health Research Center to engage with resiliency planning, prompted by an extended electricity and water outage in their rural community that lacks widespread broadband.

Pottsboro leaders and staff feel strongly that everyone must be represented in this planning and are currently working on a National Library of Medicine grant proposal to establish a learning network facilitated by libraries, which will promote collaboration among agencies in the Texoma area, focusing on enhancing preparedness, training, and responsive efforts before, during, and after disasters, ensuring the community’s ability to adapt and recover effectively.

Greyson’s work exists in the intersection between accessibility and community outreach. “We serve the entire state of Oklahoma and connect Oklahomans with technology and other services they need to do what they do,” he says. “We do outreach to Oklahomans all day, every day. That includes people who use our services, such as AT [equipment] loans or demonstrations, or, in my case, people learning how to make their digital content more accessible. Disability frequently intersects class and racial lines in our state, so we work with many different folks and communities.”

CENTERING CARE

Resources, respect, and awareness are key ingredients to creating access, but solidarity also requires care. Investing in individuals and groups of people, learning what is important to them and why, and addressing the needs they express rather than assuming what those needs are strengthens both capacity and accuracy in expanding accessibility.

Choi refers to a Texas saying: Y’all means all. “In reference to disabilities, it means visible,” she says. “Many people with disabilities feel isolated or alone because they—including me—don’t attend programs, events, or even services because getting to them can be a challenge, never mind being able to be present and maneuver through it. I have appreciated how more and more programs I see include accessibility information, such as wheelchair accessibility, and provide masks.”

For Deal, one of the most common accommodation requests she encounters for the programs she organizes pertains to individuals with hearing loss or d/Deafness. This may involve ensuring optimal seating arrangements with an unobstructed view of the presenter, or providing American Sign Language interpretation. She explains that it is crucial to recognize that approaches to meeting the range of needs within the d/Deaf and hard of hearing community, much as in other disabled communities, exhibit considerable variation and must be adaptable. “Beyond ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act] measures, I actively pursue inventive approaches to augment accessibility, drawing insights from my own experiences as a person with disabilities.”

Simple measures, such as providing large-print materials or designated quiet spaces for sensory needs, foster a more inclusive library environment. For the d/Deaf and hard of hearing community, the key lies in seeking communication preferences and avoiding assumptions. “These insights underscore the ongoing necessity for learning and adaptability in the pursuit of excellence in accessibility,” says Deal.

EXTENDED BENEFITS

Griffin has found that an effective first step is to create partnerships with organizations serving disabled and disenfranchised members of the community, as is training staff on issues of sensitivity in dealing with members of these communities. “Even if you have $0 to spend on improvements, sometimes rearranging things to be more easily navigated can make a big difference,” he says.

“Staff training on diversity of all kinds can be accessed for free online, and how you treat people with care and dignity says more than any dollar amount,” Griffin continues. “The most critical piece of this work is letting people know you hear and value them.” The staff have found that customers are willing to be patient as their needs are addressed, even if changes cannot happen right away, if they can see that attempts are being made and they are included in the process.

The return on these investments extends beyond those the accessibility is intended for. Connery believes that while assistive technology is designed to address specific needs of individuals with disabilities, its benefits extend to the broader population, enhancing overall accessibility, convenience, and quality of life. These include easy-to-find information for all patrons about the library’s AT options on its website.

Connery enumerates several specific gains, including features like subtitles or closed captions—designed for the d/Deaf or hard of hearing community—being used by a wider audience in noisy environments or by those learning a new language. Technologies like text-to-speech and spell-checkers support diverse learning styles and can be particularly helpful for people with learning disabilities, but are also widely used by students and professionals for better efficiency and accuracy. And systems designed to aid individuals with disabilities in emergencies, such as visual or vibrating alarms, can be effective in certain situations for the general population. “Assistive technologies foster an inclusive society, where people of all abilities can participate fully. This inclusion can lead to greater empathy and understanding among people,” she says.

Sossity Chiricuzio (she/they) is a queer disabled artist, advocate, educator, sensitivity reader, and author of the memoir Honey & Vinegar: Recipe for an Outlaw. She can be found online @SossityWrites.

Academic Publishers Continue Slow Progress Toward Ebook Accessibility

A growing percentage of academic ebooks are being published in the EPUB format, which could have positive implications for accessibility, according to surveys of more than 1,400 academic publishers conducted in 2020 and 2023 by EBSCO Information Services. “For ebooks with publication years 2022–2023, 77 percent were provided in EPUB, contrasting with 68 percent of ebooks with publication years 2020–2021,” EBSCO Information Services Senior Product Marketing Manager Julie Twomey writes in a report examining the surveys. “The shrinking number of ebooks provided only in PDF is a welcome improvement and reflects the commitment of many publishers to embrace EPUB.”

As the report explains, the EPUB format is much more navigable than image-based or even textual PDFs, and EPUB 3 enables publishers to include accessibility features such as embedded audio, as well as video and interactive elements.

Unfortunately, a discouraging number of publishers feel that there is not enough of a return on investment to justify prioritizing accessibility. Ten percent of respondents to the 2023 survey said that their organization has this mentality, compared with only three percent in 2020.

Offering context in a January interview with LJ, Twomey said that she had recently talked to a publisher that produces art-related ebooks, and “you can imagine, those are all visual. And they were really at a point where they know [accessibility] is important, but they didn’t know what to do first. It just seemed so overwhelming. So I think it also depends on the type of content…the size of the publisher, and the resources they have.”

Only 30 percent of respondents reported that their organization has a dedicated accessibility program, and 32 percent expressed concern about their organization lacking expertise in accessibility. On a positive note, only 30 percent of respondents to the 2023 survey thought that their organization lacked the budget and/or resources to dedicate to accessibility compliance, compared with 45 percent in 2020.

“It’s just a big hill to climb for a lot of publishers,” EBSCO Director of Product Management for eBooks Emma Waecker tells LJ. “Personally, I had hoped to see a big sea change [in the 2023 survey data]…but we’re just not quite seeing that happen yet.” Waecker adds that there are many publishers “doing a really fantastic job, who are working hard and partnering with folks like Benetech and others in the industry who can help them be sure that what they’re creating is acceptable and will be accessible over time…. All of the tools are there, the infrastructure is there, the information is there to know how to create accessible content,” but many publishers still haven’t made it a priority.

Twomey’s report recommends that publishers consider partnering with organizations such as Benetech, a nonprofit that works with EPUB accessibility and offers accessibility certification for publishers; DAISY, an international nonprofit dedicated to improving access to reading for people with print disabilities, which offers the free, open-source Ace by DAISY tool that can check EPUB files for accessibility at any point in the publishing workflow; and ASPIRE, a service developed by alt-text/image description provider textBOX that offers verification for accessibility statements. Twomey also notes that EBSCO offers to review ebook files with a proprietary accessibility validator tool that checks for Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 AA compliance in addition to content features, such as alt-text for images.

Publishers that sell ebooks in Europe will soon need to ensure that their content is compliant with the European Accessibility Act (EAA), a European Union directive that aims to streamline accessibility requirements by implementing a common set of rules across EU member countries. EAA took effect in 2019, and publishers will need to have their content compliant by next year. In EBSCO’s 2023 survey, 38 percent of respondents said that they do most of their business in Europe, yet 32 percent of those respondents said that they were uncertain what their companies were doing to prepare for EAA requirements, and 10 percent said they were doing nothing to prepare. The remaining 58 percent were working on making their ebooks Benetech Global Certified Accessible or WCAG 2.1 AA and/or EPUB 3 compliant, or at least had assembled an internal taskforce focused on accessibility. “These are encouraging steps, and these publishers should be applauded, but there is clearly still work to be done, given 42 percent of respondents doing most of their business in Europe are not aware of the EAA,” Twomey writes.

Aside from compliance requirements, making content accessible benefits all users. The EPUB 3 format “offers so many…usability features,” Waecker says. “Maybe you prefer night mode instead of a white screen…. That is theoretically an accessibility feature, but it’s also just a general useability feature. Other options like font changes, or changing the space between lines of text, changing the size of the text—all of those things that just make it easier to read, regardless of your specific set of needs” are now features that are appreciated by all users. —Matt Enis

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!