Challenges, Opportunities | Placements and Salaries Survey 2024

LJ’s 2024 Placements & Salaries Survey sees new grads grapple with questions of relocation, living wages, and job drift, but eager to begin careers in the field.

LJ’s 2024 Placements & Salaries Survey sees new grads grapple with questions of relocation, living wages, and job drift, but eager to begin careers in the field

LJ’s annual Placements and Salaries survey offers a deep dive into the data of how and where newly minted library school graduates go on to work (or, in some cases, not), tracking the shifting trends and overall evolution of employment in the information field.

LJ’s annual Placements and Salaries survey offers a deep dive into the data of how and where newly minted library school graduates go on to work (or, in some cases, not), tracking the shifting trends and overall evolution of employment in the information field.

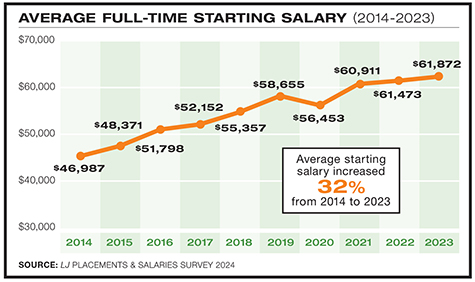

Looking back to the LIS class of 2013, many graduates found themselves focused on work in the developing social media landscape and with job titles that indicated more fluid positions than strictly “reference librarian” or “cataloger.” The 2013 responding graduates broke the longstanding sub-$45,000 average salary, earning an average of $45,560, and respondents who noted they had yet to land a position represented just 4.3 percent of the total.

A decade later, 2023 LIS graduates report an average starting salary of $61,872—a 36 percent increase over 2013—although unemployment is at six percent.

A decade later, 2023 LIS graduates report an average starting salary of $61,872—a 36 percent increase over 2013—although unemployment is at six percent.

Responses indicate the staying power of post-pandemic hybrid positions and fully remote work, a desire to work for an institution that aligns with personal values, and the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) and the burgeoning market of e-content on library work. This class of graduates has watched the rolling waves of intellectual freedom challenges hit libraries across the country and observed the decline of funding for school libraries. Despite these tough times, graduates overall indicate excitement and readiness to put their degrees to work, even if in service of getting out of a placeholder position to move toward a dream job in the field.

SUBTLE DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFTS

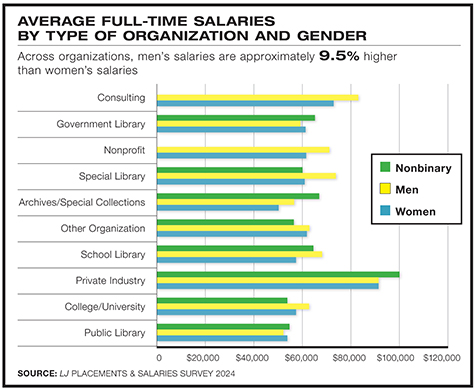

Continuing a years-long pattern, nearly three quarters of respondents identified as women (73 percent compared to last year’s 74 percent). Those identifying as male rose one percent, from 18 percent in 2022 to 19 percent in 2023. Six percent of graduates in the survey identified as nonbinary and two percent preferred not to disclose their gender, unchanged from last year.

While the racial demographics of the majority of graduates continue to skew white, there has been a marked decrease in the past three years. In 2021, 84 percent of survey respondents identified as white; that figure dropped in 2022 to 74 percent, and in 2023 is at 72 percent. Black or African American graduates rose from four percent in 2022 to six percent in 2023. Hispanic or Latine responses were unchanged from last year at eight percent, and Asian graduates were down from 10 percent in 2022 to five percent in 2023. Four percent identified as mixed race in 2023, and one percent were Middle Eastern or North African. Two percent preferred not to respond to the question on race/ethnicity.

The average age of this year’s graduates was 34.5, generally unchanged from the past several years. More than half—53 percent—of responses came from graduates between the ages of 26 and 35; 20 percent were 36–45. Thirteen percent reported being under 25, 11 percent were 46–55, and three percent were 56 or older.

These numbers are indicative of the MLS degree and library work coming as a second career for this field of graduates; in 2023, 51 percent reported that librarianship or information science is not their first professional career and 20 percent already had either a master’s degree or PhD before entering a library/information science program. Previous careers include everything from air traffic control, audio engineering, and research science to more frequent responses such as careers in education, the arts, or business management and human resources.

While the majority of 2023 graduates worked in a library either before entering or during their MLS program, the numbers have shifted since last year. One third reported working in a library both before and during graduate school, down from 39 percent in 2022. Fifteen percent worked in a library before the program, and 28 percent worked in a library while completing their degree. Twenty-four percent did not work at a library at all before or during their master’s studies. “Being in a library prior to getting my MLIS was essential to my hiring process,” said one respondent. “My employer waited until I was within graduation distance to post the job position to ensure that I could apply for it. This led me to graduate and then get hired within the same week. Making those connections before getting the degree was fundamental to my workplace success.”

A small portion of graduates (seven percent) reported that they were also working on a dual degree program or additional certification while in their MLS program. These students were most often earning Archives and Special Collections certificates, museum studies degrees, school media certifications, other master’s degrees in the arts and humanities, or management degrees both general and centered on the information field.

|

PLACEMENTS AND SALARIES BY SCHOOL AND GENDER |

||||||

| PLACEMENTS | ||||||

| SCHOOLS | TOTAL GRADUATES | NUMBER OF RESPONDENTS | WOMEN | MEN | NONBINARY | AVERAGE SALARY |

| Alabama | 101 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 1 | $62,875 |

| Albany | 127 | 25 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 60,743 |

| Arizona | 65 | 10 | 5 | - | - | 57,700 |

| Buffalo | 101 | 13 | 6 | 2 | - | 54,916 |

| Catholic | 29 | 3 | 2 | - | - | - |

| Chicago State | 21 | 11 | 5 | 2 | - | 61,571 |

| Denver | 86 | 15 | 6 | - | 1 | 56,148 |

| Emporia State | 156 | 23 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 57,054 |

| Hawai‘i Mãnoa | 15 | 7 | 5 | - | - | 75,316 |

| Illinois Urbana-Champaign | 278 | 28 | 14 | 4 | 2 | 61,415 |

| Indiana Purdue | 37 | 21 | 8 | 3 | - | 61,222 |

| Kent State* | 155 | 35 | 10 | 6 | - | 46,198 |

| Kentucky | 103 | 12 | 9 | - | - | 52,631 |

| Maryland | 111 | 26 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 54,813 |

| Michigan* | 263 | 149 | 47 | 24 | 1 | 88,994 |

| Missouri | 100 | 24 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 54,388 |

| NC Chapel Hill* | 138 | 91 | 18 | 9 | 1 | 68,386 |

| NC Greensboro | 157 | 74 | 32 | 11 | 2 | 57,430 |

| North Texas | 450 | 22 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 59,639 |

| Oklahoma | 74 | 14 | 5 | - | - | 46,634 |

| Old Dominion | 67 | 10 | 5 | - | - | 54,900 |

| Pittsburgh | 70 | 25 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 54,793 |

| Pratt | 70 | 18 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 71,581 |

| Queens | 80 | 10 | 3 | 1 | - | 64,375 |

| Rutgers | 145 | 40 | 17 | 7 | 3 | 65,783 |

| San Jose* | 656 | 143 | 42 | 11 | 3 | 65,741 |

| Simmons | 290 | 85 | 41 | 6 | 4 | 59,609 |

| Southern California | 23 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 68,500 |

| Southern Connecticut | 36 | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | 47,500 |

| Southern Mississippi | 123 | 40 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 49,157 |

| St. Catherine | 43 | 19 | 9 | - | - | 54,709 |

| St. John's | 50 | 21 | 11 | 5 | 1 | 54,976 |

| Syracuse* | 88 | 36 | 3 | 1 | - | 71,225 |

| Tennessee | 106 | 13 | 7 | 2 | - | 54,738 |

| Texas Woman's | 227 | 22 | 11 | 2 | - | 53,988 |

| Valdosta | 137 | 50 | 23 | 5 | 1 | 49,262 |

| Washington | 139 | 13 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 60,857 |

| Wayne State | 125 | 41 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 52,796 |

| Wisconsin Madison | 85 | 16 | 6 | 2 | - | 62,688 |

| Wisconsin Milwaukee | 115 | 24 | 11 | 4 | - | 56,233 |

| TOTAL | 5,242 | 1,253 | 482 | 132 | 36 | $57,787 |

|

THIS TABLE REPRESENTS PLACEMENTS AND SALARIES REPORTED AS FULL-TIME. SOME INDIVIDUALS OR SCHOOLS OMITTED INFORMATION, RENDERING INFORMATION UNUSABLE. |

||||||

THE JOB SEARCH

Nearly two-thirds (60 percent) of the class of 2023 found employment at a library or information science institution, down slightly from 63 percent last year. On average, respondents began their job searches 4.7 months ahead of graduation; 15 percent reported searching for positions a year or more prior to graduation, and 15 percent began their search upon graduation. These search strategies resulted in 43 percent of students finding work in the field prior to completing their degree; for the 57 percent who did not find jobs while in school, the average time between graduation and placement was 4.2 months. The top resources that respondents listed as helpful job search tools include Indeed (33 percent), LinkedIn (25 percent), the American Library Association (ALA) JobLIST (22 percent), state library associations (21 percent), and university or school job postings (19 percent).

Other graduates reported employment in a library/information science capacity, but not by a library or information science institution (12 percent) and employment outside of the LIS field (23 percent, up from 19 percent last year).

Those six percent of respondents who reported as unemployed were primarily seeking employment in library or information science roles (76 percent), with just over a quarter seeking employment outside the field (27 percent); 25 percent sought employment both within and outside the field. Open-ended responses in this category showed some frustration with finding work. “No one will hire me,” stated one respondent, and another noted they are relying on freelance work until securing a library job. Thirteen percent report that they are taking time off for personal reasons, while two percent share they have been furloughed or not had a contract renewed.

As graduates combed job posts, many were looking for one thing: a living wage salary. Among the open-ended responses to “What is the single most important thing you look for in an employer?,” the words “pay,” or “salary” were mentioned close to 150 times. “Benefits” got 67 mentions, and different iterations of “work-life balance” also had a strong showing. Graduates prioritized positions that align with their values, including a commitment to DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) practices and strong institutional stances on upholding intellectual freedom rights. A newly employed public library worker noted, “[I am looking for a] willingness to defend and protect libraries and our position as library staff.”

Reflecting on the job search process and what experiences or activities graduates felt helped most in finding their first placement, 43 percent mentioned internships. “Definitely get an internship. Without my internship the summer after I graduated, I would not have been hired full time by that same company,” said one respondent. “My program was incredibly cheap but also didn’t provide opportunities for internships, which I believe harmed me once I began to look for an opportunity in the field,” noted another. “Practicums/practical experience need to be embedded in LIS programs,” yet another noted. “We need to do better at preparing students without burdening them to take on volunteer or unpaid internships.”

Adrienne Johnson Pucilowska, a new academic librarian, said she applied for many jobs, but was not able to move forward until she accepted a “paid, part-time internship that set me up for success. Upon [securing] the internship, I got multiple job offers. I was fortunate...to have the financial means to accept part-time work for eight months, but I understand many people would not have been able to take that chance.”

SCHOOL SUPPORT

In addition to the student survey, LJ fields a concurrent Placements and Salaries survey for MLS-granting institutions; the 40 schools that responded in 2023 reported offering numerous tools and avenues of support for students ready to launch their career. Most institutions utilize listserv announcements (95 percent), include job postings on their website (48 percent), promote jobs through student groups and activities (48 percent), and boost job postings via social media (45 percent). Thirteen percent of MLS institutions reported having formal placement services within the program, and 38 percent noted that there are placement services available at the higher university level. Other services included student hubs with job postings in a program’s learning management system, career fairs, and faculty communications. On average, schools listed 347 different employment opportunities through their various channels.

MLS programs can also support graduates by connecting them with professional organizations at the state and national level, where networking can result in job leads; schools like Old Dominion University, the University of Denver, and San José State University mention active student chapters of ALA and its subgroups. Programs at the University of Southern California and University of Arizona pay student membership fees, and Indiana University–Purdue University and Wayne State University stated that they offer travel grants, scholarships, and other forms of sponsorship to support professional development at meetings and conferences.

Mentorship is often considered a key component of finding success in a new professional career, and 26 percent of MLIS-granting schools offer a formal mentoring program. The University of Michigan School of Information offers “Alumni

Career Connections...designed to help students build professional relationships and prepare for the job market through ‘micro mentoring’ meetings with alumni experts in all industries and fields,” wrote Director of Career Development Joanna Kroll. Last April marked the launch of the University of Alabama’s new mentoring program: “We place MLIS and Book Arts students and early career librarians and BA professionals with seasoned LIS and Book Arts professionals,” noted Joi Mahand, assistant director of academic programs. “We have 19 mentor/mentee matches.”

More than 80 percent of institutions in the survey reported it took about the same amount of time as last year for graduates to find placements; nine percent felt it took more time and six percent said it took less. Even with the opportunities reported by these institutions, several graduates said they did not feel supported in their job hunt. “Despite so much lip service given to DEI and graduate job placement, I received inadequate help in both realms and struggled post-graduation to make ends meet,” noted one. “I felt the school’s program where I received my master’s was not helpful in assisting those of us who were remotely attending to find an internship or position post-graduation. They are hyper-focused on jobs in the local area,” said another.

TRADITIONAL AND EMERGING ROLES

While public libraries continue to draw the most new degree earners, 2023 was the third year in a row in which the share of graduates moving into public library roles dropped slightly, moving from 33 percent (2021) to 30 percent. Academic libraries have also seen a dip, posting a 20 percent share—down from 24 percent last year. Sixteen percent of graduates moved into private industry, up one percent from last year. Employers in this category included big names such as Spotify, PayPal, Microsoft, and Amazon. Other organizations hiring new graduates included K–12 school libraries, both public and private (seven percent of responses), archives/special collections (four percent), special libraries, government libraries, and government agencies, all at three percent of placements. Two percent of graduates indicated they are in consulting roles, and one percent are working for LIS-relevant vendors. The three percent reporting work in “other” organizations include those who have had difficult job searches within LIS: comments included being employed in food service, retail, and childcare.

The survey asked respondents to name both their formal job title and indicate what job assignments they are responsible for in their current placement; 37 percent of titles include the word “librarian.” Many traditional roles rise to the top: reference/information services (46 percent), collection development/acquisitions (43 percent), outreach (39 percent), circulation (32 percent), and patron programming (31 percent).

The survey asked respondents to name both their formal job title and indicate what job assignments they are responsible for in their current placement; 37 percent of titles include the word “librarian.” Many traditional roles rise to the top: reference/information services (46 percent), collection development/acquisitions (43 percent), outreach (39 percent), circulation (32 percent), and patron programming (31 percent).

When asked if respondents consider their job to fall in the category of emerging library services, nine percent answered yes. Digital content job assignments came in at 20 percent, a significant leap from the 3.4 percent reported a decade ago; other relatively new roles reported include makerspace work (10 percent), emerging technologies (nine percent), and AI (four percent).

One respondent working for an LIS vendor listed their position as “developing AI technology for library software products,” while several others noted their role is to learn and then educate their communities on tools such as AI and virtual reality (VR). “We teach AI in credit-bearing information literacy courses,” noted Hayley Holloway, a new academic librarian working at the University of Baltimore. “We are also looking into developing teaching resources using VR.” Another recently placed academic librarian pointed out that “AI and copyright is an emerging issue.”

Information workers in archives, special collections, and preservation are met with a host of new challenges in the current technological landscape; one graduate working for a special library stated that they “have to deal with digital assets in many formats, including new/emerging formats that didn’t exist when the library was founded, such as GIFs and TikTok-style videos,” echoing another response listing “born-digital preservation” as an emerging part of their job. A recent graduate wrote that their archival work now includes “experimenting in the application of AI toward transcription and/or translation of documents,” a technological advance that was just a glimmer on the horizon 10 years ago.

School librarians also reported emerging roles in the work they do with primary and secondary students. “I teach students and staff about AI. I also incorporate a lot of emerging services (i.e., various types of tech) into my role as school librarian,” said one. Another replied that at their middle school library, “we teach ‘digital life’ classes in which we discuss emergent technology with the students, including AI.”

Some of the responding MLS institutions added their own perspectives on emerging job categories or positions they saw represented by this year’s class of graduates: One mentioned seeing an uptick in scholarly communications postings; another noted that positions related to open educational resources in higher education were on the rise.

Trends in pandemic-driven flexible work agreements leading to hybrid or fully remote positions continue to adjust to workplace needs and expectations. While the majority (71 percent) of full-time employed graduates are working fully in-person (up from 64 percent last year), five percent (down from nine percent) are fully remote, and 24 percent are hybrid. Recent graduates working in private industry (33 percent) and consultants (67 percent) are the most likely to be

working exclusively from home. None of those working in public libraries, school libraries, and in archives/special collections work remotely.

WHERE ARE GRADUATES GOING?

WHERE ARE GRADUATES GOING?

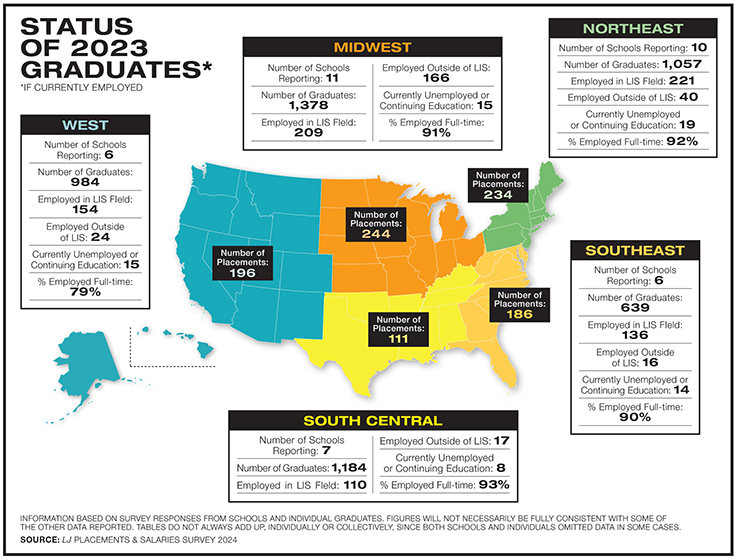

The class of 2023 found jobs across the country and beyond, with 18 percent relocating for their placement. The Midwest and Northeast ranked highest for placements (23 percent and 22 percent respectively), followed by the Southeast (18 percent), Pacific (14 percent), South Central (11 percent), Mountain (five percent), remote worker (five percent), and international (three percent). The Pacific region had the highest average full-time salary, at $75,526; the South-Central region had the lowest, with an average of $54,189.

Relocation worked for some graduates, but didn’t for many others. About two thirds remained at the organization where they were employed during their graduate program. “I knew I wanted to relocate to Maryland, so I searched Google for each Maryland county ‘+ library jobs,’ and followed the job postings on each county’s library website,” said one respondent. “I was fortunate that I was able to relocate for a position,” said another. “I know this is not always possible and makes it harder for many new graduates to find employment in the field.”

Several other respondents noted this difficulty of finding nearby placements. “I am an older individual, and relocation was never an option,” said one. However, they added, “I live in a major city with many library jobs/opportunities, so I was able to find a position that worked for me and my circumstances.”

One graduate explained that despite her experience, the inability to relocate presents an ongoing barrier: “I worked in a library for 20 years before beginning my MLIS. I’ve been applying for five years since leaving that role, and got my MLIS in that time, but have yet to be hired as a librarian again. I do not have the flexibility to move for a position at this time.”

PLACEHOLDER OR DREAM JOB?

As to post-degree placements, 74 percent of those surveyed report they are satisfied with their position. “I work full-time as an access services specialist in a large academic library—my dream job!” wrote one respondent. A public librarian noted, “Outreach is the most fulfilling job that I’ve ever worked.” Recent graduate Helen Cozart appreciates her placement, recognizing that she might not be so fulfilled were she to have found work in a different organization: “I am in a small community college with only two librarians, so I have a huge variety of responsibilities and autonomy. I like everything I do but would probably get bored if I had only one or two tasks like librarians in bigger schools.”

Many expect that they will need to put in some time at entry level roles before moving into a career that more closely matches their ideal. “It’s my first librarian job,” noted one respondent. “The system I’m working for promotes from within, so I should move up within a year.” Other factors contributing to job satisfaction include working for supportive managers, feeling a sense of purpose, loving the community where they work, liking their primary job assignment, and finding autonomy and support for independent work. One graduate candidly stated, “I am new enough not to have time to be unsatisfied.”

Of those graduates who remained with the same employer throughout their master’s program, 23 percent moved from support to professional roles, 13 percent moved to full-time from part-time positions or internships, 32 percent received a raise, 24 percent received a promotion, and two percent became eligible for tenure. A public librarian wrote that their job is “a promotion [from] the position that I had while in school. I also love the community and teens I serve, and I feel like I handpicked this job for myself.”

One public librarian was not feeling as supported, however. “While I love my current job, I am dissatisfied with my organization’s lack of transparent policy regarding pay grades and advancement steps,” they said. “I received only a $.40/hour raise for my MLS degree.”

For those 26 percent who are unsatisfied with their current placement, poor pay is a common denominator. An academic library worker noted they are “working in the same position I held before and during my time as a graduate student, which I am now overqualified and underpaid for.”

“The public library I work at pays the lowest in the area and [it] is not enough to live off of,” said one graduate, and another public library worker mentioned they “enjoy the work, but I work three library jobs and still do not make a living wage.” A school librarian wrote that their placement “does not pay enough for me to make ends meet unassisted, and does not utilize the full scope of my MLIS degree.”

Some graduates had to take a job outside their preferred specialty, leading to feelings of dissatisfaction. “I would prefer to work at a library rather than for a library vendor,” said one, and “It’s not in archives,” wrote another currently working in a public library. “Academic libraries are not where I want to be. I want to be in a public library (preferably in youth services),” said another graduate.

While a hybrid or remote workplace may be a good fit for some, a new graduate working in a fully remote position for a

vendor has found it challenging: “I have trouble asking for help and advocating for myself in a fully remote workspace. I feel disconnected from my coworkers, and get distracted easily, which has led me to feel a lot of stress and insecurity in my work.”

The topic of job satisfaction carries extra weight when graduates share their student loan debt; on average, the class of 2023 carries $35.5 thousand in student loans, though 44 percent did graduate without incurring any debt. Fifty-three percent of students with loans expect public service loan forgiveness after 10 years with qualifying employers, and this factor made a difference in choosing a placement for 55 percent of those expecting loan forgiveness.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE MLS GRADS

Survey respondents could choose to leave comments on the challenges and triumphs of finding placement and share recommendations from their job search process. Suggestions for future graduates included:

- Take volunteer opportunities in fields of interest to develop practical skills as well as connections within that respective field.

- Research prospective employers; speak to current employees to learn more about the organization. One recent graduate advised: “Remember interviews go both ways, they’re interviewing you, but you’re also interviewing them.”

- Practice interviewing.

- Consider roles that may initially not feel like a perfect fit but could lead to additional opportunities.

- Treat “required” skills as a suggestion and apply even if you don’t check every box—specific skill training may be an option. “I applied to positions where I didn’t meet all of the qualifications, and I forced myself to doubt the initial belief that I wasn’t qualified for the position,” said one respondent.

- Weigh the pros and cons of a blanket approach to job searching, applying for everything possible, versus a more refined or selective approach.

- “I found a book entitled Get the Job: Academic Library Hiring for the New Librarian by Meggan Press very helpful,” noted one graduate. “This book provides a methodical way for finding and applying to academic jobs.”

- Write a thank-you note following interviews.

Overall, despite challenges of locale, salary, and role specifics, for the most part MLS graduates are finding work that supports their values, gives a sense of purpose, and capitalizes on their skillsets. A new public librarian wrote, “I am working with a population I care about and have the opportunity to provide programming that meets their needs.”

April Witteveen is the library director at the Oregon State University–Cascades campus in Bend, OR.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!