Get That Grant

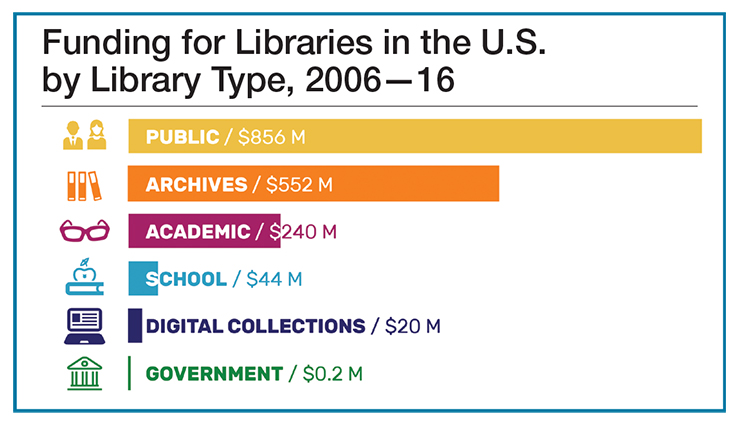

Since 2016, more than 7,100 funders gave over $586 million in grants to more than 5,400 recipients for library-related projects. Amounts ranged from $10–$25 prompted by individual donors (e.g., employer matching donations, or AmazonSmile percentage of purchase) to thousands of libraries to a $21 million-plus legacy grant for the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). Total dollars were almost equal for program development, capital and infrastructure improvement, and general support. The foundations include the usual suspects, such as Bill & Melinda Gates or Andrew W. Mellon, but the most active funders by number of grants are from donor-advised funds and community foundations.

Your library can get a spot on the list of recipients, even if you have no skills or staff. Simple steps and free tools can significantly expand your funding options without raising taxes.

FIRST STEPS

Start small. Find one distinct, direct services program at your library that has clear community benefit and a history of measurable success. Funders will consider a pilot program, but you’ll need to reassure them about why and how it will succeed. Although support is growing for general operating costs, funders still prefer programs that directly enhance the community, especially for your organization’s first request.

Start with a relatively small amount, not a $1 million building campaign. Applying to multiple funders will increase your chances of getting the support, but one funder might cover the entire amount. Requests for larger amounts will always involve having to apply to more donors; usually include coordinating input, data, and documentation from your organization’s departments and executives; and possibly mean more conversations with your prospective funders.

Keep in mind that grants are not quick. Grants research now should be for funds that you expect to need in nine to 12 months.

Find answers to these three questions to help find the right funders:

- Who are you serving?

- What are you doing for them?

- Where will you do this work?

Questions that do not matter:

- Which funders are in my city, county, state?

- Which funders take unsolicited applications?

Many funders give beyond where they live. Looking only at local donors will likely miss opportunities. About half of foundations don’t accept uninvited proposals, but as long as they still give money for your kind of work, you can get on their radar by seeing where your network crosses theirs and asking for a referral. (This is the best way even for funders that do accept uninvited proposals.)

Set up a system to track the information you’ll collect. Start simple—capture the information related to one funder in a Word or Google Doc—then add complexity only when required. Set up another system to track the program you want to fund, especially the data you will collect to show that it achieved its goals.

Look for funders who support what you are doing (e.g., STEM, job training, literacy), not just what you are (a library).

WHERE TO LOOK

Google is a popular starting point, but it won’t help find the majority of grantmakers, which lack websites and online channels and, probably, receive loads of applicants. Over half of all private foundations are small and unstaffed, but they’re still giving money. Start with free resources:

- VISUALIZING FUNDING FOR LIBRARIES is a data tool that shows grants made since 2006 to libraries and similar institutions. You can search by location or subject to see who’s given or gotten grants in your geographic or subject area, as well as by several other parameters. Funder and recipient profiles include contact info and program areas.

- GRANTS.GOV is the main source for government grants. It has many search filters and the ability to sign up for alerts of new opportunities that match your search, plus tutorials, because government grants are usually complicated.

- REQUESTS FOR PROPOSALS (RFPs) are the foundation version of the government’s funding opportunity announcements. You can get free weekly email alerts of newly posted ones at Philanthropy News Digest, the news service of Foundation Center (FC). (FC is a nonprofit that collects and shares data about foundations and corporations and connects nonprofits to training, resources, and tools. The author leads FC’s Online Librarian team.) However, don’t rely only on RFPs because you’ll miss most of your prospects: only a few hundred out of 100,000-plus foundations publish them.

- FOUNDATION DIRECTORY ONLINE (FDO) is FC’s flagship research tool, containing more than 140,000 private, community, and public foundations; corporate giving programs; foreign grantmakers; and federal agencies, with over four million grants added annually. Search results are based on past grants data because past giving best predicts future giving. You can filter your search by subject and geographic focus, as well as ten-plus other fields. For example, if you’re trying to fund a program in Atlanta that teaches job skills to new immigrants, your search setup might look like this (note, “libraries” isn’t mentioned because this search focuses on the program, not the provider):

-

- Subject Area = Employment

- Population Served = Immigrants and migrants

- Geographic Focus = Atlanta (Georgia, United States)

Funder profiles contain application guidelines, key people, and recent giving trends, among other useful data. FDO is a subscription product but is free to use at more than 400 Funding Information Network partners, including many libraries. Several more offer it as part of database collections.

Be on the lookout for grant announcements via Google Alerts or similar tools. Likewise, when you find strong prospects, follow their communication channels. They will publish announcements on their own sites first.

FOLLOW DIRECTIONS

The most important thing to remember about writing proposals is to follow the funder’s instructions. Some will ask for a letter first; others, the whole proposal. Not following directions gives the funder an easy reason to reject your request.

In the absence of detailed application instructions, FC’s proposal template works for most cases; it was developed with foundation input. A free 60-minute course, Introduction to Proposal Writing, covers what goes into each part of the proposal.

Apply to multiple funders because you will get rejected by some. The most common reason is simply that demand exceeded supply. When in doubt, ask the funder why your proposal was not selected. Any information you get can only help your next request. Find out if it’s “no for now, or no forever.” If it’s “no for now”: don’t give up on a funder because they reject one proposal; next time their goals, the pool of competitors, or your application may have evolved—or all of the above.

PERSUASIVE PROPOSALS

Beyond the basics—a well-written proposal that describes a needed, well-designed program with clear goals—what makes some proposals stand out?

Present outcomes, not outputs. Focus on measuring the program’s impact, rather than attendance. For more information on how to measure outcomes, see Jennifer Koerber’s “Meaningful Measures” and Samantha Becker’s “Outcomes, Impacts, and Indicators."

Focus on connecting the program outcomes to community needs and the funder’s priorities. Although your organization plays an important role, the focus of the proposal should be the people served. For example, your cover letter might close with, “Your support of $20,000 will provide 100 immigrants with critical skills to seek and secure employment.” Notice there’s no mention of the provider (your library).

Embed your impact in a compelling human interest story. Narratives with characters, emotions, and plot can put a face on those outcomes and make them meaningful.

That first grant is often the hardest, but the payoff could be huge. It’s also the start of a (hopefully) long, productive relationship with that funder, and it can open doors to partnering with other community donors.

FURTHER LEARNING

- Grantseeking for Libraries: Top 10 Practices for Foundation Funding, a free, self-paced course created with WebJunction. See more options under “Training”

on Visualizing Funding for Libraries. - Introduction to Finding Grants, a free course, is offered live or recorded, online or in-person.

- Storytelling resources on GrantSpace.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Jeanette Pedginski

Well written and concise! Thank you for all the links!Posted : Jan 30, 2019 04:58