2018 School Spending Survey Report

Q&A: Josh King; A Former Advance Man Talks Political Pitfalls and Campaign Stagecraft

"I stayed at the White House for five years, far longer than the average tenure back then, but life on the road is incompatible with being a grounded husband and father, so it was time to say goodbye."

Photo by James Miller

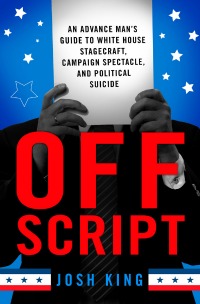

For most readers, your book Off Script: An Advance Man’s Guide to White House Stagecraft, Campaign Spectacle, and Political Suicide (St. Martin’s; LJ 4/1/16; ow.ly/ES4t30090YL) will be an introduction to the role of advance men and women in presidential campaigns. Could you briefly describe the position? Advance people are the movie producers and storytellers of political campaigns. They help a candidate get to and from a setting in which they can send their message and facilitate the media’s ability to distribute that message. Advance work is probably as old as the republic, but it’s the continuation of the effort that helped Franklin D. Roosevelt travel around America to survey the Arsenal of Democracy without having his disability on display; of John F. Kennedy conjuring large, seemingly spontaneous crowds; and in my case, helping Bill Clinton convince voters that his presidency was “the bridge to the 21st century.” Your subtitle mentions “political suicide.” What candidates for whom you’ve worked have found themselves hoisted on their own swords as a result of actions taken by advance staff? “Dukakis and the tank” in 1988 inaugurated what I call the “Age of Optics” and is generally regarded as the worst political event in history. The campaign staff and the advance team decided to try to make Michael Dukakis look like a credible commander-in-chief, but it backfired miserably. Dukakis was derided in the press in the days that followed, which was then piled on by his Republican opponents, including Vice President George H.W. Bush. Then, five weeks later, the “tank ad” appeared in front of a huge national audience during the third game of the World Series, cementing the event’s disastrous status in perpetuity. It seems the 2016 election has seen traditional campaign rules and etiquette tossed out the window. Has this changed the jobs of advance staff? I haven’t done advance work in this campaign cycle, so I can’t say exactly how the advance role has changed. But what has been clear as I have talked to and watched advance men and women work since I left the White House during the Clinton years is that there is far less autonomy and a lot less creativity exercised by advance people working on the road. I saw some of this first-hand when I “came out of retirement” in 2009 to lead an advance trip for President Barack Obama to Trinidad to participate in the Summit of the Americas. I found myself on a much tighter leash than I ever was during the Clinton years. Much of your story occurs in what you call the “Age of Optics.” What started and ended this age? Is a new era being spawned by the current presidential campaign? The “Age of Optics” describes a period roughly from 1988 to the present, where what a candidate or politician does in public often does more to shape opinion than what he or she says in public. Ronald Reagan, of course, harnessed the power of the visual to great effect, but it wasn’t until CNN rose to prominence, later joined by MSNBC and Fox News, that the action on stage became a regular focal point for discussion during prime time. I call the 2004 campaign the “high water mark” of the Age of Optics, before Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, when a glut of imagery began to dilute its effect. Still, Donald Trump has proven in 2015 and 2016 that there is nothing more powerful in politics as stage performance and strategic manipulation of the media. You call the Obama administration the “Vanilla Presidency.” Why? President Obama and his communications team showed themselves to be studious observers of the “Age of Optics,” conscious that the stakes were higher for the 44th president about not screwing up on stage. He had many enemies upon assuming office who were ready to pounce on any mistake, and he and his team seemed determined to avoid them by playing it straight, or vanilla, with lots of blue drapes, podiums, and Teleprompters. The Obama White House was also much stricter in “controlling the image,” closing many events traditionally open to the media and using official photos, distributed through social media platforms, to send their message. By the end of Obama’s two terms, he seemed to find comfort in nontraditional platforms for communication, such as late-night comedy shows, prime time entertainment shows, taped sketches designed for the Internet, and podcasts. Your book gives much attention to Michael Dukakis’s aforementioned tank incident. What do you consider the second greatest presidential flub that resulted from poor advance work? The worst mistakes of political stagecraft are those that get magnified and resonate long past the “news cycle” in which they were produced. Dukakis’s tank ride, because it was made into a paid ad and recirculated on national television, had lasting effects through Election Day. The same thing happened in 2004, when John Kerry made an ill-advised windsurfing expedition in the waters off Nantucket. The George W. Bush/Dick Cheney team then turned into a disastrous (for Kerry) ad showing him as a flip-flopper. It happened again in 2012, when Mitt Romney thought he was being patriotic by singing his off-key rendition of “America the Beautiful” at a rally in Florida. Why did you leave advance work? Advance work isn’t all world travel and great storytelling challenges. In 1997, I found myself planning the annual pardon the Thanksgiving Turkey for the fifth year in a row and thought I’d be a turkey too if I did it for much longer. As much as I believe political stagecraft is serious work with potentially game-changing implications, it’s generally a younger person’s game. I stayed at the White House for five years, far longer than the average tenure back then, but life on the road is incompatible with being a grounded husband and father, so it was time to say goodbye.

It seems the 2016 election has seen traditional campaign rules and etiquette tossed out the window. Has this changed the jobs of advance staff? I haven’t done advance work in this campaign cycle, so I can’t say exactly how the advance role has changed. But what has been clear as I have talked to and watched advance men and women work since I left the White House during the Clinton years is that there is far less autonomy and a lot less creativity exercised by advance people working on the road. I saw some of this first-hand when I “came out of retirement” in 2009 to lead an advance trip for President Barack Obama to Trinidad to participate in the Summit of the Americas. I found myself on a much tighter leash than I ever was during the Clinton years. Much of your story occurs in what you call the “Age of Optics.” What started and ended this age? Is a new era being spawned by the current presidential campaign? The “Age of Optics” describes a period roughly from 1988 to the present, where what a candidate or politician does in public often does more to shape opinion than what he or she says in public. Ronald Reagan, of course, harnessed the power of the visual to great effect, but it wasn’t until CNN rose to prominence, later joined by MSNBC and Fox News, that the action on stage became a regular focal point for discussion during prime time. I call the 2004 campaign the “high water mark” of the Age of Optics, before Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, when a glut of imagery began to dilute its effect. Still, Donald Trump has proven in 2015 and 2016 that there is nothing more powerful in politics as stage performance and strategic manipulation of the media. You call the Obama administration the “Vanilla Presidency.” Why? President Obama and his communications team showed themselves to be studious observers of the “Age of Optics,” conscious that the stakes were higher for the 44th president about not screwing up on stage. He had many enemies upon assuming office who were ready to pounce on any mistake, and he and his team seemed determined to avoid them by playing it straight, or vanilla, with lots of blue drapes, podiums, and Teleprompters. The Obama White House was also much stricter in “controlling the image,” closing many events traditionally open to the media and using official photos, distributed through social media platforms, to send their message. By the end of Obama’s two terms, he seemed to find comfort in nontraditional platforms for communication, such as late-night comedy shows, prime time entertainment shows, taped sketches designed for the Internet, and podcasts. Your book gives much attention to Michael Dukakis’s aforementioned tank incident. What do you consider the second greatest presidential flub that resulted from poor advance work? The worst mistakes of political stagecraft are those that get magnified and resonate long past the “news cycle” in which they were produced. Dukakis’s tank ride, because it was made into a paid ad and recirculated on national television, had lasting effects through Election Day. The same thing happened in 2004, when John Kerry made an ill-advised windsurfing expedition in the waters off Nantucket. The George W. Bush/Dick Cheney team then turned into a disastrous (for Kerry) ad showing him as a flip-flopper. It happened again in 2012, when Mitt Romney thought he was being patriotic by singing his off-key rendition of “America the Beautiful” at a rally in Florida. Why did you leave advance work? Advance work isn’t all world travel and great storytelling challenges. In 1997, I found myself planning the annual pardon the Thanksgiving Turkey for the fifth year in a row and thought I’d be a turkey too if I did it for much longer. As much as I believe political stagecraft is serious work with potentially game-changing implications, it’s generally a younger person’s game. I stayed at the White House for five years, far longer than the average tenure back then, but life on the road is incompatible with being a grounded husband and father, so it was time to say goodbye. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

TECHNOLOGY

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!