ALA Featured Speakers Talk of Equity, Change, Hope| ALA Annual 2021

The all-virtual format of the American Library Association (ALA) 2021 Annual conference, held June 23–29, meant new options for attendees who previously hadn’t been able to travel to the event, and also allowed ALA to put together an impressive roster of speakers.

|

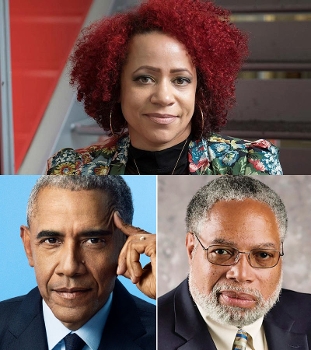

ALA Annual Conference speakers Nikole-Hannah-Jones, top, and Barack Obama and Lonnie Bunch III, bottom |

The all-virtual format of the American Library Association (ALA) 2021 Annual conference, held June 23–29, meant new options for attendees who previously hadn’t been able to travel to the event, and also allowed ALA to put together an impressive roster of speakers. In between Nikole Hannah-Jones’s Opening Session and Barack Obama’s closer, a lineup of dynamic guests attracted thousands of viewers apiece.

Feminist icon Billie Jean King spoke of her lifelong journey advocating for pay and gender equity in sports, her “shero” Althea Gibson, and the need to “keep learning and keep learning how to learn.” President’s Program speaker Isabel Wilkerson, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author ofThe Warmth of Other Suns and Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, discussed how deep the concept of caste lies in this country, and why this is the moment we need to reckon with it—the murder of George Floyd, the Capitol riots, and the sheer number of years Black people were enslaved. “No adult alive today will be alive at the point at which African Americans will have been free for as long as African Americans were enslaved,” she noted. ALA President Julius C. Jefferson Jr. chatted with Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Director R. Crosby Kemper III about what it was like for Kemper to step in to head a federal agency just before the pandemic hit, the business of grantmaking, and the launch of the REopening Archives, Libraries, and Museums (REALM) Project, which researched COVID-19 transmission via library materials.

1619 AND BEYOND

The Opening Session speaker, journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, was awarded the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for the 1619 Project, the New York Times Magazine's exploration of the legacy of Black Americans; The 1619 Project will be published as a book in November. Speaking on June 24 with Chris Jackson, publisher and editor-in-chief of One World, an imprint of Penguin Random House, Hannah-Jones talked about the origin of the 1619 Project—stretching back to a high school Black studies elective that transformed her worldview. That glimpse made her realize that there was far more out there than she was being taught in school—and that the omission was intentional.

Hannah-Jones began a course of self-study, learning—among many other things—that the first African slaves were brought to Colonial America in 1619, marking the beginning of American slavery. As the 400-year anniversary approached, she began thinking about how to mark it, given the fact that many Americans weren’t familiar with the significance of the date. “I just really felt that I needed to do something to force an acknowledgment,” she said, as well as “a reckoning with how foundational slavery was to our society.” Hannah-Jones pitched the New York Times Magazine on an entire issue of exploring connections to slavery in contemporary society.

Hannah-Jones made sure to highlight democracy and capitalism—“the two pillars of American identity,” both built through slavery—and music, because, she said, Black music is synonymous with American music. As Jackson pointed out, the project isn’t about Black people in America—it’s about America. Hannah-Jones brought together a number of influential scholars and journalists to brainstorm elements that would surprise and engage readers; her own journalism is rooted in history and archival research, and grappling with that legacy on a popular platform was critical. The project’s reception pleased her. “I think there’s been an aggressive aversion to dealing with this history, a kind of elective amnesia,” she told Jackson. Readers lined up around the block to buy copies of the magazine, and the first printing sold out immediately. She heard from people of all ages, in every walk of life, who said the 1619 Project had opened their eyes and explained much that hadn’t made sense before.

Jackson agreed—that rather than tell an “irredeemable” story about oppression in this country, “you have this group of people enslaved, abused, who somehow managed to keep the flame of actual democracy burning in this country for hundreds of years, and that is one of the great miraculous stories of world history.”

Hannah-Jones has now expanded the project into book format to give it longevity and a broader reach, and enlarge its scope with the help of photographs, literary contributions, and expanded research. What she discovered as she continued her scholarship, she said, is “a story that all of us, no matter our race, can embrace and be proud of and really gives us a template for an America that is inclusive and beautiful, and…that is fighting to live up to its highest ideals. And that’s what I wish people with an open mind would take from this story. No one has to be ashamed for things that they haven’t personally done, but you have to acknowledge the way that that legacy has shaped your lives and shapes our country. And in confronting that legacy, we can be liberated from it.”

BRINGING “CHANGE” TO LIFE

The Library Marketplace Opening, on June 23, featured Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman and author/illustrator Loren Long. Moderated by Librarian of Congress Dr. Carla Hayden, the two discussed their collaboration on Gorman’s book Change Sings, and the process of turning a poem into a book for young readers. “I think of poems as divisible by units of sound, and children’s books are divisible by units of scene,” said Gorman. “Every line break…had to speak for itself.” The challenge for an illustrator tackling verse, said Long, is to bring a narrative to it that’s accessible to a child, Gorman was delighted at how Long could take her concepts and give them texture and light, and “take something that can feel so overwhelming to a child, like change, and make it feel all the more intimate and proximate to who they are.”

Gorman read a few pages from the book, and Long, clearly moved, spoke of his thoughts on visually weaving together the concepts of change and music-making, his use of color, and how his composition lined up with her intentions. Gorman also talked about her considerations for the adults—caregivers, teachers, and librarians—who would be reading and giving this book to the children in their lives. “It was important for me that not only the young reader went on a journey, but the adults went on a journey with them,” she said, “It wasn’t making adults take a step back in the book, it was actually having them take a step forward, along with their children, to dream further and longer and bigger.”

MOVING THE BOULDER UP THE HILL

The closing session on June 29 featured former President Barack Obama in conversation with Lonnie G. Bunch III, the 14th Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and author most recently of A Fool's Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the age of Bush, Obama, and Trump. The two began by discussing Obama’s 2020 memoir, A Promised Land—the title of which describes both his life and this country as works in progress.

We move forward while carrying with us the weight of history, Obama said. “One of the things that was necessary as President of the United States, but I think is generally necessary for all of us as global citizens now, as well as citizens of the United States, is to have some background—some idea—of how did we get to where we are? Because if we don’t know that, then it’s very hard for us to figure out how we’re going to get to know where we’re going.”

When Bunch praised him for being “comfortable with ambiguity,” Obama attributed it to growing up with the very different stories of his parents, a midwestern white mother and a Black African father. “For me to reconcile those worlds and understand myself as whole, I’ve got to be able to look and say, ‘What are the stories on each side of that equation?’” he said. “I can’t resort as easily to stock figures of heroes and villains. It turns out people are complicated”—as are countries and cultures, he said. Part of learning to live with that ambiguity is “being able to look squarely at things, to hold two contradictory ideas in your head at the same time. And that is something, by the way, that democracy requires.”

Which is not to say everything is relative, he added. In the Civil Rights march across Edmund Pettus Bridge, “John Lewis was right, and the guys on the other side were wrong.” Moral decisions need to be made, but people can’t expect simple answers in the process.

“What gives you hope for this country?” asked Bunch. Young people, Obama answered, citing his daughters and their peers. “They are as sophisticated, as thoughtful, as idealistic as any generation I think we’ve ever seen. They are biased in the direction of inclusion.” They’re not cynical about change, but they are about institutions and big business. Part of the task of restoring America, he said, is empowering young people to imagine what new institutions will look like. The process is similar to reimagining museums and libraries to engage the communities they serve, he added.

Obama touched on the January 6 Capitol riots, the power of social media to misinform people, and the lack of what he calls the “guardrails” that should be in place around many democratic institutions, admitting, “That worries me. And I think we should all be worried.” Certain core precepts and principles are fraying, he said, and we have our work cut out for us to reunify the country. In a nod to the audience, Obama said, what librarians do is more important than ever: “Figuring out how do we provide our fellow citizens with a shared set of baseline narratives around which we can make our democracy work.”

In terms of equity, many things have changed in our lifetimes, he told Bunch, but having a handful of Black men in positions of power doesn’t readjust the scales. “Our country never did the kind of full accounting that would allow for changes in institutions to make up for that difficult past and to make sure that we’re more reflective about our future.” You can make a strong argument for reparations, he said, but politically it’s a difficult notion, and some of these structural inequalities will continue to exist in our society—including policing used to keep a lid on poor communities. Those patterns are deeply ingrained. But when people start having more hope, he noted, that opens up the possibility to translate that generosity into programs and institutions that make things better. Going back to their earlier conversation about ambiguity, Obama said, “You understand that whatever you do is not going to be everything, but if it moves the boulder up the hill, then it’s useful.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!