Exploring History and Nutrition in UMN’s Kirschner Cookbook Collection | Archives Deep Dive

The Doris S. Kirschner Cookbook Collection at the University of Minnesota–St. Paul provides an excellent window into the history of food, cooking, and technology—and some surprises—through cookbooks and other related ephemera.

|

Doris Kirschner’s textbook/notes from one of her courses at UMNPhoto by Megan Kocher |

With the availability of recipes and cooking videos online today, it’s hard to imagine a time when preparing foods required local knowledge or a cookbook—and we take ingredient measurements and cooking temperatures in recipes for granted. But this wasn’t always the case. The Doris S. Kirschner Cookbook Collection at the University of Minnesota–St. Paul (UMN) provides an excellent window into the history of food, cooking, and technology—and some surprises—through cookbooks and other related ephemera.

With cookbooks and pamphlets dating from 1841 through the present day, the collection contains about 6,013 items. The collection has a strong representation of Minnesotan works, including community and kosher cookbooks.

“We can learn about ourselves as a society from the cookbooks,” explained Megan Kocher, science librarian and curator for the Kirschner collection. It’s been eye-opening for Kocher to see how food intersects so much with all parts of life, she added.

For instance, Kocher wondered, why were there so many cookbooks from gas companies from mid-century? She learned that many gas companies had home economics departments because they were trying to sell stoves to consumers. Plus, she noted, the recipes began to list temperatures because the availability of stoves meant home chefs could cook at more precise temperatures.

The collection began with a donation of about 1,000 items from Doris S. Kirschner, an alumna of the UMN home economics department. Kirschner began collecting cookbooks at 17, but did not get her degree until after her children were in school. She collected local Minnesota cookbooks, and international cookbooks when she joined her husband as he traveled abroad for work. Kirschner kept a kosher kitchen, so the collection includes kosher and local Jewish community cookbooks. She chose to donate her materials to UNM when she downsized her house in 1985 so they could be used by students, scholars, and anyone with an interest in the history of cookbooks.

The collection, originally housed at the Department of Food Science and Nutrition, now in Magrath Library, has grown thanks to subsequent collection donations, as well as Kirschner family funds used to facilitate purchases of James Beard award–winning books, local cookbooks, and more.

Scholars and classes use the collection in many different ways across disciplines. Kocher noted that one student was studying binding on community cookbooks, while the “Travels in Typography” class in the College of Design explored the use of typography to enhance recipes.

|

Page from one of the collections' banana pamphletsPhoto by Megan Kocher |

“It’s so interesting what you can get out of cookbooks that’s not even related to food,” Kocher said. Books on bananas can open a window into history and colonialism. Scholars can explore gender roles and expectations through Jell-O pamphlets or racism and race in cookbooks from prior decades.

The collection is strong on Minnesota food history, including cookbooks from national companies like Pillsbury and Betty Crocker that were located in the state. “It has a good representation of white American perspective on what they’re eating,” Kocher noted.

She also pointed out that the collection helps to highlight local immigrant communities in the state and how they have changed. The cookbooks are a mix of both community and commercially published works, but published cookbooks are more “retrospective,” she explained. For instance, Scandinavian cookbooks began as community cookbooks in the 1950s and 1960s, with traditionally published cookbooks coming out later. The collection has been acquiring Somali cookbooks published recently by local presses in the last five years, reflecting the growth of Somali immigrant communities in Minnesota.

“It tells you so much about a place and the people there, and the history of immigration, and how that shaped the food that we eat now,” Kocher explained.

|

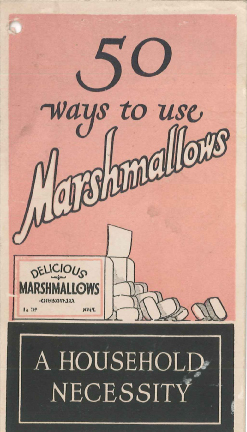

Marshmallow pamphletPhoto by Megan Kocher |

One of her favorite parts of the collection is a marshmallow pamphlet from the 1940s. “Marshmallows contain only pure, wholesome ingredients,” it reads. “They are, therefore, the best sweets for children. Let them eat all they want, either plain or in table dishes.” She is fascinated by how the discourse about sugar and health has changed over the decades. “You can really see how we are creating stories about what is healthy and what is pure,” Kocher said.

As for the Jell-O pamphlets, she pointed out that while it’s fun to laugh at the over-the-top recipes, it's important to take a moment to think about why they existed. At the time, Jell-O was considered a fancy dish, and people wanted to show off. They also evoke the story of working women needing faster foods, histories of appliances such as stoves and refrigerators, and present a picture of what was considered the ideal housewife.

The oldest part of the collection is The Kentucky Housewife, an 1841 cookbook by Lettice Bryan. Kocher pointed out that it shows how our understanding of recipes has changed over the years. For instance, there’s a recipe for oyster soup that is just a paragraph with instructions not to boil the soup for too long. Often these books assumed that someone had taught the user how to cook, so they did not always include the ingredient lists and measurements we see in recipes today.

Kocher also enjoys seeing the traces of Doris Kirschner in the collection. Kirschner’s own cookbooks have notes in the margins, and monthlong meal plans for her busy family. “Cookbooks are something that can be so personal and handed down through families,” Kocher said. “I can see what she liked and what her family liked. It gives you this connection to another person.”

The collection is currently noncirculating, but is open for use in the libraries to students and the public. Works that are out of copyright are digitized and available on the collection website, along with a blog highlighting parts of the collection.

However, Kocher cautioned that UNM doesn’t have the space to take everyone’s cookbook donations. Instead, she advises people to think about what they can learn about their own family cookbooks. “I think it gives you an interesting perspective on the cookbooks in your life and in your house, your family, your grandma’s cookbooks, whatever. I really encourage people to engage with those,” she said.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!