Fine Farewells: LJ's 2022 Fines and Fees Survey

LJ’s 2022 Fines and Fees Survey shows a transformed landscape since 2017.

LJ’s 2022 Fines and Fees Survey shows a transformed landscape since 2017

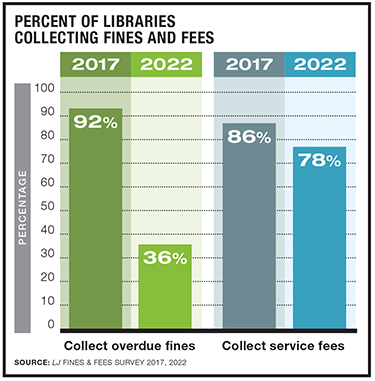

Many public libraries are finding it valuable—even profitable in ways that go beyond revenue—to reduce and eliminate some fees, particularly late fines, as shown by the responses to LJ’s 2022 Fines and Fees Survey. In comparison to LJ’s 2017 survey, the percentage of U.S. public libraries charging patrons overdue fines dropped dramatically from 92 to 36. From near universal to a minority represents an amazing sea change in the core assumptions of how U.S. public libraries operate in only five years. Some other fees (such as those for printing, copying, and faxing) are still charged by 78 percent of libraries, still a significant decrease from 2017’s 86 percent.

Many public libraries are finding it valuable—even profitable in ways that go beyond revenue—to reduce and eliminate some fees, particularly late fines, as shown by the responses to LJ’s 2022 Fines and Fees Survey. In comparison to LJ’s 2017 survey, the percentage of U.S. public libraries charging patrons overdue fines dropped dramatically from 92 to 36. From near universal to a minority represents an amazing sea change in the core assumptions of how U.S. public libraries operate in only five years. Some other fees (such as those for printing, copying, and faxing) are still charged by 78 percent of libraries, still a significant decrease from 2017’s 86 percent.

While eliminating late fees was not an option for some libraries surveyed in 2022, the respondents whose libraries did abolish them pointed to increases in patron satisfaction and participation and to staff morale. One librarian in Minnesota enthused, “It has engendered a lot of good will in the community and we have seen people—and even materials!—return to the libraries after years away.”

Three hundred twenty people participated in the survey. In every size category, especially the largest, the number of libraries that have dropped fines have increased in the past five years.

Among the 64 percent of libraries that do not currently charge late fees, certain trends emerge. A nearly universal 95 percent of this group previously charged fines for overdue materials. About half (54 percent) eliminated fees during the COVID-19 pandemic between 2020 and 2022, and many chose to keep this policy afterward.

Some hoped the lack of fines would increase patrons’ usage of the library, and in a number of cases this appears to be true. A quarter (26 percent) said circulation in their libraries has increased, about the same (25 percent) stated that it hadn’t, and the remaining 49 percent did not know—comments indicated that they were unsure whether circulation changes were attributable to changes in fine policy, the pandemic, or both.

Eight percent of newly fine-free libraries, according to the survey, attempted to replace or offset lost fine revenue through fundraising, collecting voluntary donations at the circulation desk (such as via a fine forgiveness jar), and increasing their local budgeting request. One library added a passport agency; another started charging for for-profit/private meeting room reservations.

|

LIBRARY CHARGES A FEE FOR... |

||

| 2017 | 2022 | |

| Printing | 94% | 95% |

| Copy machine/Photocopier | 97% | 94% |

| Faxing | n/a | 61% |

| Processing fee for replacement of lost/damaged items | 54% | 53% |

| Library card replacement | 77% | 52% |

| Non-resident fee | 48% | 48% |

| Space rental/Meeting rooms | 38% | 34% |

| Debt collection processing fee | 34% | 25% |

| Interlibrary loan/Document delivery | 32% | 22% |

| 3-D printing | 6% | 19% |

| Scanning | 16% | 11% |

| Test Proctoring | n/a | 10% |

| Notary services | n/a | 6% |

| Holds not picked up | 12% | 3% |

| Special Collections/Genealogy services | 3% | 2% |

|

SOURCE: LJ FINES & FEES SURVEY 2017, 2022 |

||

A WEALTH OF REASONS

Respondents who chose to eliminate fines listed various grounds for their decisions, including opportunities to foster good will and improve customer service, promote social justice, and adhere to their mission statements and directives. In some cases, the decision to discontinue late fees came about because libraries successfully suspended them during the COVID pandemic and decided to continue doing so. Other libraries made the decision to not charge late fees decades ago.

Some looked at the success of other libraries that have gone fine-free. Adult Program Coordinator and Reference Librarian Kristina Giovanni of Bloomingdale Public Library, IL, recounted, “A neighboring library stopped charging fines/fees in 2019 and their success, on top of the pandemic in 2020 that involved patrons holding onto materials far longer than we would typically allow, made going fine-free the most sensible option.”

San Francisco Public Library (SFPL) Strategic Data Analyst Zahir Mammadzada described how the library came to a similar conclusion. “Based on extensive research of national publications, conversations with library leaders and experts across the country, surveys of patrons and staff, and rigorous analysis of SFPL data, SFPL concluded that the use of overdue fines did not align with the library’s goals,” he wrote. “Overdue fines restrict access and exacerbate inequality by disproportionately affecting low-income and racial-minority communities, create conflict between patrons and the library, require an inefficient use of staff time, and do not consistently ensure borrowed materials end up back on library shelves.” Many other respondents agreed.

San Francisco Public Library (SFPL) Strategic Data Analyst Zahir Mammadzada described how the library came to a similar conclusion. “Based on extensive research of national publications, conversations with library leaders and experts across the country, surveys of patrons and staff, and rigorous analysis of SFPL data, SFPL concluded that the use of overdue fines did not align with the library’s goals,” he wrote. “Overdue fines restrict access and exacerbate inequality by disproportionately affecting low-income and racial-minority communities, create conflict between patrons and the library, require an inefficient use of staff time, and do not consistently ensure borrowed materials end up back on library shelves.” Many other respondents agreed.

President and CEO Tonya Aikens explained that Howard County Library System (HCLS), MD, found the decision to be both practical and in accordance with the library’s philosophy. The lack of late fees “removes a barrier to access,” she wrote. “Being fine-free is in keeping with HCLS’s commitment to equity and inclusion, and it positions us to more fully live our mission of providing high quality public education for all Howard County residents. At any given time, seven percent of customers have their accounts blocked due to overdue fines. Full access has a dividend for Howard County—we all benefit from a curious and engaged community.”

Libraries’ consideration of communities’ needs was often a factor. “We originally stopped charging fines because of COVID,” wrote Tami Cox, assistant director of East Moline Public Library, IL. “Our mission is to serve our patrons and some of them cannot afford to pay a $10 fine. That is literally a dinner for their family, and why would we want someone to have to pick between food and a library fine?” Casandria Crane, director of American Fork Library, UT, commented, “We realized the poorest in our community were paying the most.”

COLLECTING FEES

All fee-collecting libraries accept cash payments. Personal checks and money orders are accepted at 88 percent of libraries, a sizable majority but still down from 2017’s 96 percent. Conversely, the percentage of libraries that accept credit and debit card payment for fines has increased from 59 to nearly three quarters, at 73 percent. Four percent of libraries take digital payment methods through apps such as Paypal, Venmo, and Apple Pay.

Most (92 percent) libraries’ circulation staff notify and remind patrons about owed fines. Four-fifths (82 percent) inform patrons on their online accounts, and two-thirds (64 percent) use email. Other methods include paper mail (54 percent), phone calls (41 percent), texts (37 percent), printed messages on checkout slips (31 percent), and mobile apps (17 percent). Ninety-one percent of libraries train staff to communicate with patrons about fines owed and the concept of shared resources.

Ninety-six percent of libraries charging late fees suspend patrons’ borrowing privileges after they have reached a specific amount of outstanding fees, at an average of $11. When fines remain outstanding too long, about a third (31 percent) contact collection agencies. This is significantly fewer than 2017’s 44 percent. The average fine threshold that prompts libraries to refer to a collection agency is $39. Nine percent of respondents’ libraries have pursued legal action for unpaid fines, 70 percent have not, and 21 percent were unsure.

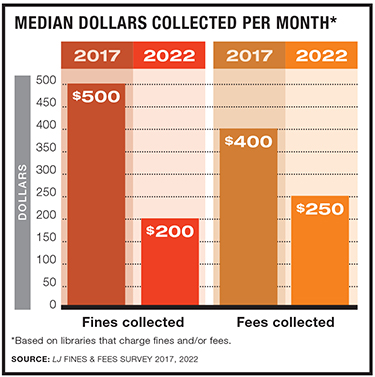

Among the 78 percent of libraries that charge fees for services, the most common are for printing (95 percent), copying (94 percent), and faxing (61 percent). About half charge processing fees for replacement of lost and damaged items (53 percent), library card replacement (52 percent), and cards for nonresidents (48 percent). Most (81 percent) do not charge for participation in programs and events. The median monthly revenue from service fees is $250, 38 percent lower than the median in 2017 ($400).

|

PAYMENT METHODS ACCEPTED |

||

| 2017 | 2022 | |

| Cash | 100% | 100% |

| Check or money order | 96% | 88% |

| Credit/Debit card | 59% | 73% |

| Digital payments (e.g. PayPal, Venmo, Apple Pay) | n/a | 4% |

|

SOURCE: LJ FINES & FEES SURVEY 2017, 2022 |

||

LATE RETURNS

LATE RETURNS

At libraries that charge fines, it is estimated that 12.9 percent of all borrowed items are returned late, down from 2017’s 14.9 percent, which may have to do with the introduction of automatic renewals. Some 60 percent of responding libraries automatically renew borrowed items. The survey did not ask respondents at libraries that do not charge fines what percent of borrowed materials are returned late or how late those items are.

Although there are fewer late returns at fine-charging libraries than in 2017, overdue items remain out longer. In 2017, 88 percent estimated that the average overdue book is returned to the library within one week of the due date. In 2022, this percentage fell to 69 percent. The lateness tends be shorter at libraries that automatically renew items.

SHRINKING FINE REVENUE

Most libraries that still charge late fees do so out of necessity. One respondent in Pennsylvania explained, “We need the money as it is built into our budget. Even without the money we receive for fines, we are responsible for raising $25,000 per year in fundraising activities just to balance our budget.” Similarly, according to a New Jersey respondent, “We still rely on fines to support our operating budget. Until we can replace the revenue with another source, we’re not in a position to get rid of them entirely.”

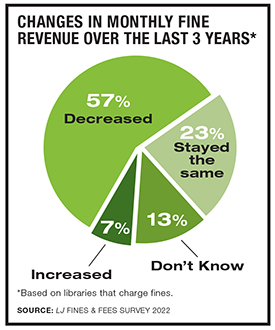

Libraries that collect fines are earning less revenue from them in 2022 than in 2017. The monthly median fell dramatically from $500 to $200. Fifty-seven percent of respondents answered that fine revenue has decreased since 2019, citing various reasons. Half (51 percent) of the respondents blame decreased circulation and COVID for the decrease, 39 percent cite more digital checkouts, and 28 percent say it is the result of instituting automatic renewals. A quarter also changed their fine structure, such as eliminating fines for children’s materials.

Fee-collecting libraries disperse these funds in various ways. Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) place funds in a general library fund; 22 percent allocate the funds to a general municipality or county fund. Only 10 percent earmark the funds for library materials, and half as many use these funds for programming.

COST OF COLLECTION

COST OF COLLECTION

When deciding whether or not to go fine-free, the cost-effectiveness of collecting outstanding fines is a consideration for some. Libraries estimate that they spend an average of $198 per month collecting fines in staff time, collection fees, etc.—seven percent of the average monthly fine income ($3,001).

Library Manager SueAnn Burkhardt explained the process of how Luther Callaway Public Library, FL, approached the question: “A study was done by the library taking into consideration the staff hours spent on notifying patrons of overdue items, collecting overdue fines, reports and delivery to finance department. It was found to be a loss for the library, not worth the time spent.” However, she added, “We were told specifically, by the county, to continue collecting fines regardless of costs incurred by the library.”

County Librarian Todd Deck said that Tehama County Library, CA, determined that stopping late fees saves the library money and benefits both staff and patrons. “It isn’t financially responsible,” he wrote about collecting fines. “Last year, the library collected $6,000 from overdue fines. This represents less than 1.9 percent of the library’s overall annual operating budget. We estimate that going fine-free would result in a reduction of staff time to collect and process overdue fines; it will also encourage the return of library materials, so many items will not have to be repurchased. Once implemented at the Tehama County Library, a fine-free program is estimated to save $7,280 annually.” (He also noted that it promotes the health and safety of patrons and staff by cutting down on physical transactions during the ongoing pandemic.)

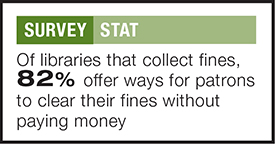

FINE ALTERNATIVES

Of libraries that collect fines, 82 percent—up from 61 percent in 2017—offer ways for patrons to clear their fines without paying money. Sixty-nine percent have waived fines for various reasons. Thirty-six percent allow people to donate food to charity drives in lieu of payment. Other methods include fine amnesty periods (31 percent), volunteering in exchange for fines (9 percent), and donations of materials to the library (5 percent). Five percent allow children and teens to “read down their fines.”

About two-thirds (68 percent) have considered eliminating fines altogether, twice the number that were considering going fine-free in 2017. By comparison, only two percent of those not charging fines are considering adding them. Respondents listed several reasons why their libraries still charge fines besides financial dependence on them. Some cited a belief that patrons must be held accountable for lateness, and that without consequences nothing would stop people from returning materials late or simply keeping them. Others said that even when directors and staff favored eliminating some or all fees, municipal officials and library boards do not support this course of action.

COMPELLING ARGUMENTS

COMPELLING ARGUMENTS

While some directors and staff members received enthusiastic support from their boards or local government for dropping late fees, others found challenges to getting consensus from stakeholders. “Emotionally and morally almost everyone was in favor of it,” recalled Jessica Paulsen, patron experience manager at Jefferson County Public Library, CO. “Practically, especially financially, was harder for some people to reconcile.”

Yolo County, CA, used a test case to convince stakeholders. “We went fine-free for youth first and monitored the results,” explained Director Mark Fink. “The data demonstrated an increase in new cardholders, and existing cardholders using the library more, and there was not a substantial increase in lost/missing items. This data made consensus easy after it was presented.” Clintonville Public Library, WI, also met success with a similar approach.

In some cases, the success of other libraries’ abolishment of overdue fees managed to convince stakeholders, as did the success of automatic renewals.

Advocates used a combination of hard data and anecdotal evidence about the virtues of dropping late fines. Meg Lojek, director of McCall Public Library, ID, wrote, “Honestly, one of the biggest arguments in our favor was that, during COVID we stopped charging fines due to wanting people to stay home and stay safe. Then we were able to show the limited impact on our budget and no impact on people getting materials back to the library. Emotionally, it is easy to tell the stories about families who don’t want to borrow books because of the fines and to show that it is an equity issue—perhaps those who could benefit from the library the most are the same people who fear they will have to pay fines.”

Advocates used a combination of hard data and anecdotal evidence about the virtues of dropping late fines. Meg Lojek, director of McCall Public Library, ID, wrote, “Honestly, one of the biggest arguments in our favor was that, during COVID we stopped charging fines due to wanting people to stay home and stay safe. Then we were able to show the limited impact on our budget and no impact on people getting materials back to the library. Emotionally, it is easy to tell the stories about families who don’t want to borrow books because of the fines and to show that it is an equity issue—perhaps those who could benefit from the library the most are the same people who fear they will have to pay fines.”

This point was illustrated by Deck’s comment: “Lots of data was helpful. But the single most impactful tool was reading a letter from an eight-year-old asking for forgiveness for having late library books.”

The late fee discussion for Delaware County District Library, OH, also looked at a personal request, wrote Director George Needham. “This was all it took to seal the deal: One letter from a woman who couldn’t pay a small fine she owed, but offered to work off her fine so that her kids could have access to the collection. I had the numbers for what we would be giving up, but the letter was the emotional impact that pushed the discussion over.”

Alicia Blake, assistant branch manager at Worcester County Public Library, MD, offered advice for libraries considering eliminating overdue fees: “Fine receipts are less than 0.4 percent of our county library’s annual budget. It was and is such an insignificant amount in library revenue, yet patrons who had fines potentially stopped visiting the library altogether. My advice: ask yourself, Would you rather collect 0.4 percent profit or let a child take books home to read with [the adults in their lives], increase literacy rates in your county, and ultimately change the way your community approaches library use (for the good)?”

As libraries continue to gather data, public input, and successful examples from their peers—particularly as the coming years let them judge the evidence on its own merits, rather than as a response to pandemic shutdowns—they will be better able to evaluate their approach to collecting fines and fees. It will be interesting to see what LJ’s 2027 survey reveals.

METHODOLOGY

The Fines and Fees survey was emailed to a random list of U.S. public library employees on May 26, 2022, with a reminder on June 16. The survey closed on July 1, with 320 U.S. public library responses. Data reported in total was weighted by library size to match the weights used in the 2017 Fines and Fees survey.

The complete 2022 Fines and Fees survey can be downloaded here.

Andrew Gerber, Young Adult and Media Librarian for North Brunswick Public Library, NJ, has previously written articles for LJ and Medical References Services Quarterly.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!