Most Academic Librarians Are Sexually Harassed at Work | Peer to Peer Review

In the #MeToo era, we reflected on how widespread sexual harassment felt in our field, and we wanted to know whether that feeling was supported by evidence. A research team consisting of three academic librarians and two sociologists who specialize in data analysis decided to find out.

Candice: One of my colleagues at a former place of work was an older white man who would stare at women’s chests and legs, including mine. When I complained to the director, I was told to ignore him, as he was “harmless.” When I heard some women students were avoiding the reference desk because he made them uncomfortable, I confronted him. He apologized for staring and after a beat, said, “But if women don’t want men to stare, they shouldn’t wear skirts.”

Candice: One of my colleagues at a former place of work was an older white man who would stare at women’s chests and legs, including mine. When I complained to the director, I was told to ignore him, as he was “harmless.” When I heard some women students were avoiding the reference desk because he made them uncomfortable, I confronted him. He apologized for staring and after a beat, said, “But if women don’t want men to stare, they shouldn’t wear skirts.”

Jennifer K: During one long Saturday shift on the reference desk, a patron at least 40 years my senior, after hanging around for a while, asked whether I would like to go on a date (I wouldn’t), whether I had a boyfriend (I did), what time my shift was over, where my car was parked… I finally asked him to stop talking to me unless he had a reference question. Luckily for me, I worked in a library with on-site security. When the patron was waiting for me outside after my shift, a long glare from the head of security, who walked me to my car, was enough to send him scurrying. I don’t want to know what would have happened if I didn’t have a security escort.

Jennifer RW: I have had many experiences over the years of coworkers and patrons at various libraries staring at my chest while I talk with them. I would always ignore it because I had been taught that this was to be expected from men. I would occasionally mention the instances to coworkers, but I never reported them to supervisors.

These are only one story each from the librarian coauthors of this study. Nearly everyone we asked has one similar. In the #MeToo era, we reflected on how widespread sexual harassment felt in our field, and we wanted to know whether that feeling was supported by evidence. A research team consisting of three academic librarians and two sociologists who specialize in data analysis decided to find out, and reported our results in a recently published article in College & Research Libraries (C&RL), “#MeToo in the Academic Library: A Quantitative Measurement of the Prevalence of Sexual Harassment in Academic Libraries.”

Surprisingly little research already existed about this question, despite the fact that the little evidence available pointed to extremely high prevalence of workplace sexual harassment for librarians. The research team decided to start by measuring harassment in academic libraries only, and hope to measure public libraries in a separate project. Decades of workplace sexual harassment (SH) assessment pointed the team toward the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ)—an imperfect tool, but by far the most widely used to measure the incidence of SH, and the best for this purpose. Most uses of the SEQ measure harassment from coworkers. A “client sexual harassment” version measures SH by customers, clients, etc. The research team developed a survey combining the coworker and client variants and sent it widely to listservs in the field. The survey invitation was worded to make it clear that anyone working in an academic library was invited to fill out the survey, regardless of their rank or whether they had experienced sexual harassment or not. The survey was open for 24 days, and we received 613 completed survey responses.

“Sexual harassment” has numerous definitions. In psychology, it is viewed as a continuum of behaviors of both severity and related harm, or—put another way—some kinds of harassment are worse than others. Most workplaces and individuals recognize the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) definition, but there is clear evidence that sexual harassment that lands below the line of the EEOC definition still causes demonstrable, measurable harm to both the individual and the institution. This harm is discussed at length in the Chelsea R. Willness et al. study A Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents and Consequences of Workplace Sexual Harassment.

Because the phrase “sexual harassment” is loaded, the survey we used asked people to identify whether they have experienced specific inappropriate behaviors, without explicitly naming them as examples of sexual harassment. We found that gender harassment (“generalized sexist remarks and behavior”) and seductive behavior (“inappropriate and offensive, but essentially sanction-free sexual advances”) were both very common. Gender harassment was reported by 78.1 percent of respondents, and seductive behavior was reported by 64.4 percent. Sexual assault was reported by 35.2 percent of respondents. It’s important to understand that nearly all of those reports were characterized by “deliberate touching that made the respondent uncomfortable,” and not “fondling, or attempted or forced sexual intercourse.” The most serious categories of sexual harassment, including the latter definition of sexual assault, sexual bribery (2.4 percent), and sexual coercion (1.5 percent), were not absent, but were comparatively rare.

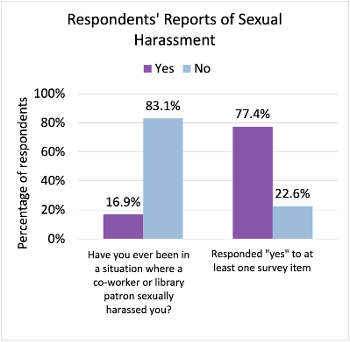

The survey, after measuring these experiences, asked respondents whether they have ever experienced sexual harassment at work. Most respondents who filled out the survey (83.1 percent) said “no” indicating that they had not experienced SH, even though most respondents (77.4 percent) had reported at least one experience of sexual harassment in the preceding questions. The authors believe that this discrepancy is a reflection on the lack of consensus on a definition of SH, as well as a measurement of how sexual harassment is normalized in our workplaces.

Most respondents in the sample (89 percent) indicated they were white and the remaining 11 percent that they were either a racial minority, biracial, or multiracial. There was no significant difference in results due to the race of victims. We had asked about cis- vs. trans- gender, but the sample size of transgender was so small that we had to exclude from results.

Existing research about workplace SH in other fields is consistent in many ways. Two examples of this research include articles on Sexual Harassment in Nursing and Sexual Harassment in Social Work Field Placements. The targets of SH are almost all women, and SH is more prevalent in workplaces that are male dominated (e.g. military), in which clients believe they have power over their targets’ ability to succeed at work (e.g. restaurants, real estate), or in which harassers believe they might be anonymous or that harassment will be ignored, unobserved, or unpunished (e.g. nursing, libraries). SH exacts extremely well-documented harms from both targets and their institutions, in the form of lower job satisfaction, higher turnover, absenteeism, health care costs, and physical and mental health impacts for both targets and bystanders. Workplaces have a legal requirement to protect their employees from sexual harassment from both coworkers and clients. In addition to being the right thing to do, it is also in the organization’s best interest.

It doesn’t have to be this way. As a field, we can do better. We urge libraries to adopt clear policies protecting their employees from sexual harassment, and to offer consistent training and processes that believe and support their employees who experience harassment at work.

Candice Benjes-Small is Head of Research, William & Mary Libraries, Williamsburg, VA and Jennifer Knievel is Professor and Lead, Researcher & Collections Engagement, University of Colorado Boulder Libraries. Jennifer Resor-Whicker is Head of Research Services, Dr. Allison Wisecup is Associate Professor of Sociology, and Dr. Joanna Hunter is Associate Professor of Sociology, all three at Radford University, VA.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy: