Princeton “Language To Be Looked At” Course Involves Students in Special Collections Acquisition

Before the COVID pandemic, Princeton University instructors Joshua Kotin and Irene Small were looking forward to coteaching an undergraduate class, “Language To Be Looked At,” exploring concrete and visual poetry. In concrete poetry, the visual elements of a poem—typography and symbols and their arrangement on the page, as well as the printed matter itself—are critical components of its meaning.

|

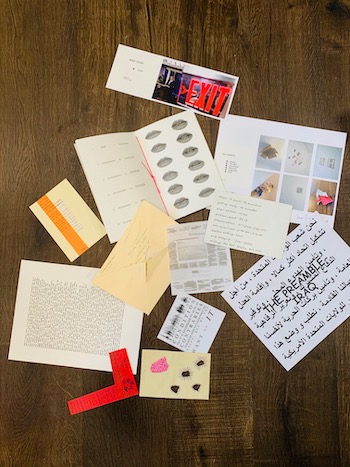

Student contributions to the class's assembling magazine.Photo by Irene Small |

For most instructors, the pivot to teaching suddenly far-flung students during the past year involved transitioning to Zoom and other remote instruction platforms. But how does a course adapt when it involves the physical aspects of printed matter as well as its content?

Before the COVID pandemic, Princeton University instructors Joshua Kotin and Irene Small were looking forward to coteaching an undergraduate class, “Language To Be Looked At,” exploring concrete and visual poetry. In concrete poetry, the visual elements of a poem—typography and symbols and their arrangement on the page, as well as the printed matter itself—are critical components of its meaning.

The class was created as part of Princeton’s Teaching with Collections series, which incorporates the university’s various special collection resources into undergraduate and graduate courses. Kotin, associate professor of English, and Small, associate professor of art and archaeology, originally planned to bring students together at Firestone Library Special Collections to learn about concrete poetry and curate an exhibition at the end of the semester—but the campus shutdown in March 2020 meant they needed to rethink the course in a hurry. “When the pandemic struck, we realized we weren't going to be able to teach in Special Collections,” Kotin told LJ. “We had to redesign the class, kind of from scratch.”

Instead, they chose to focus on a series of historical and contemporary poets and artists, inviting guests to Zoom into the classroom; having students assemble a concrete poetry collection as a group; and winding up the course with an exercise in which they asked students to identify and procure new materials for the library to purchase.

BUILDING COLLECTIONS, DESIGNING A CLASS

When he first came to Princeton in 2011, Kotin noticed that the university’s collections were strong in Modernist poetry and magazines but less so in postwar work. He ended up taking students in his postwar American poetry class into Manhattan to view New York Public Library’s Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature to find the material he needed. After talking about the gaps in Princeton’s holdings, Kotin and several university librarians—including Gabriel Swift, librarian for academic programs and curator of American books and Western Americana, and Professional Specialist Sarah Hamerman, who signed on to catalog new acquisitions—began building a postwar “little magazine” and poetry collection, with a strong component of concrete poetry.

“When you start developing a strength, it's like a snowball,” said Kotin. “The more things you get, the more dealers reach out to you, the more collectors reach out to donate material, the more you can justify acquiring more material based on what you already have, because it fills a facet or a niche that is not already covered.” In 2014, at the unveiling of a recently acquired archive, he struck up a conversation with Small, who has an expertise in Brazilian concrete poetry, and the two decided to teach a course together.

Bringing together Small’s background as an art historian and Kotin’s as a professor of literature, they designed a course that would look at the history and examples of concrete poetry, from William Blake’s illustrated poems to Sol LeWitt and John Cage, encompassing a range of mid- and late-20th century work from the United States, Brazil, England, and other European countries.

But when the pandemic shut down the campus, “we were really thrown for a loop,” said Kotin. The class had originally been designed to be exploratory, with students handling the material at the library; Kotin and Small had expected to spend time that summer in Special Collections planning their syllabus.

“We started to think about the physicality of the objects, the materiality of the objects, which is kind of the whole point of having this class in special collections,” said Swift, who had been involved in planning the course from the beginning, “and how were we going to transmit those aspects on a screen. The three of us really started to think about ways to break through the screen.”

RECONFIGURING THE COURSE

|

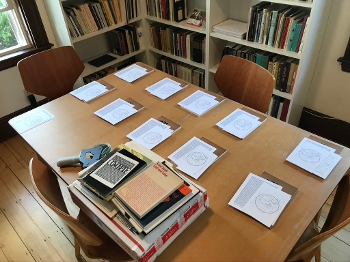

Packets of material prepared for each student: examples of concrete poetry, including original publications and facsimiles, and construction materials for assignments and re-enactments (postcards were donated by Siglio Press).Photo by Joshua Kotin |

Although the library offered to digitize any materials students might need, Kotin and Small were concerned. Investigating concrete poetry required that they experience aspects of the physical book from the weight of the paper to the printing techniques used. The Princeton Humanities Council offered a small budget to purchase printed matter and send it directly to students. “One of the great things about concrete poetry, especially from its heyday,” said Kotin—“it's beautiful and scarce, but it's not particularly expensive.”

He reached out to Berkeley, CA bookseller Jeff Maser, who selected two different pieces for each of the class’s 10 students. “We went through a couple of iterations,” recalled Kotin. “He would take pictures [and say] what about this stuff? And I said, ‘Can we have more things that are not in English, or aren't from English speaking countries?’ And he went back and reselected.” Small put together some facsimiles of books that she had planned to teach with, and—together with some Fluxus-related exercises that students would do as part of their classwork—at the beginning of the course, each student received a packet of material and books in the mail.

Students chose one piece from their packets to copy 13 times and send back to Small, who collated them into 13 “assemblings”—magazine-like creations. Each student received a copy of the group work, and a final copy was donated to Princeton’s Mudd Manuscript Library.

Hamerman put together a video tour of Firestone’s concrete and visual poetry archives, examining poetry that needed to be manipulated or seen from different angles on camera. “She set up a camera so that she could open them and interact with them,” said Small, “both the close reading element and also show [students], this is what it's like to encounter a box of archives. This is what it would look like to open it and sift through all of these folders.” Kotin and Small invited guests—several of whom would not have been able to participate in-person even pre-pandemic. Artist Fia Backström, a former Princeton instructor, Zoomed in to discuss her own work, as did artist Adam Pendleton, who visited from his New York studio, in conversation with Whitney Museum curator Adrienne Edwards.

Then, in collaboration with Swift, “we developed this final assignment where they would do research themselves [to fill] gaps in the collection,” said Kotin—“how to collect material, how to develop relationships with rare book dealers, how to know how to develop an argument about justifying a work requisition, what was reasonable to request. We shared a lot of rare book catalogs, and a lot of our own experiences writing justifications to the library to acquire material.”

During the semester, Special Collections acquired the archive of Paula Claire, a British concrete poet, and used that process as an example. The main challenge, however, was not only filling the gaps in Princeton’s collection but identifying where those gaps lay—thinking about who wasn’t represented and why. Craig Dworkin, poet and professor of English at the University of Utah, spoke to the class on African American concrete poetry in 1960s Cleveland, and an anthology, Women in Concrete Poetry: 1959–1979 (Primary Information, 2020), served as a source of names to research. Students were asked “to really think about why Princeton hadn't been as active in acquiring material by women, or by people of color,” said Kotin. “Also thinking about how collections represent the priorities of staff members and students at the time.”

Some spoke with rare book dealers, some to librarians, and to complete the assignment they each wrote an essay explaining their interest in the material they highlighted, why it was an important addition to Princeton’s collection of concrete and visual poetry, and practical steps that could be taken to acquire it.

By the course’s end “They understood how these collections were formed and what the process was, and they [virtually] went out into the trade,” Swift said. “They went to ABAA [Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America] dealers. They went to electronic book fairs, and got material that way. They suggested some purchases from auction houses, and dealer catalogs that came out weekly. The professors pointed them to all modes of acquisition.”

“Both my parents are librarians, so I kind of grew up in libraries, and at Princeton I felt very comfortable there,” Kotin told LJ. He wants students to realize that collections are not set in stone, and “that there's a certain kind of flexibility. Asking [the library] to buy a book is not like asking the Princeton Art Museum to buy a painting. They can really make it their own, or use the library to help them develop their interests.”

Archives and collections can be overwhelming for students—or any researcher—noted Small. “Sometimes that prevents people from entering into the space. So especially within this context, where we couldn’t physically enter, we wanted to convey both the kind of slowness and care of archival work. What does it look like to look at a single object and inspect its particularity, and draw meaning out of that?”

The students surpassed all expectations, all agreed. “We were totally amazed by what they came up with,” Kotin recalled. “There was a lot of material they suggested that we never heard of before, or we hadn't been able to locate. And we ended up acquiring almost all of it. In one case, a student identified something that was at auction the next day. We couldn't do that, but we did find something by that artist to acquire.”

“It really was kind of a perfect class to teach during the pandemic” Small told LJ, “to think about the distance between us, and virtuality and materiality, in different ways.” Swift, who curates American books, was surprised and pleased to see the students looking at materials from around the world, and looped in his colleagues in global collections to purchase what fell outside of his domain.

CONTINUING THE CONNECTION

Kotin and Small hope to reconvene the class informally this fall, in person, at Firestone Library to examine the material and see how it fits together—and maybe go out for a meal after. They would also like to teach some version of the course again that would be closer to their original vision. “But I don't ever want a pandemic situation that is going to force us to be as resourceful as we turned out to be,” said Kotin. He added, “We were lucky that we had each other to plan and to bounce ideas off of, and we were lucky that we had amazing students. The students rose to the occasion—they were really invested.”

Swift is adapting the acquisition assignment for Archiving the American West, a course he’s teaching with professor of history Martha Sandweiss. “The students have an assignment that is modeled after the concrete poetry curatorial assignment—they have gone out into the trade,” he told LJ. “In this example, they're supposed to come up with a subject they want to collect, and then they come back with eight to 10 acquisition opportunities in that subject. Then we vote on which ones we think have real merit, as a class. I've been acquiring pieces.” Subjects have included land rights and nuclear developments in the West, Indigenous boarding schools, and the history of Asian Americans and African Americans in the West.

Working with students on what Swift calls “connected collections” has “tremendous upside for the curators,” he added. The students “have pushed me in directions that I wouldn't necessarily think about, and they are bringing up challenging issues such as repatriation for Indigenous material. Those are the right discussions to have.”

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing