The Long Game | Editorial

30 years of underfunding will take decades to fix.

30 years of underfunding will take decades to fix

I remember 1992 well—it was the year I graduated from high school. It was also, I just learned, the last year in which government (combined local, state, and federal) fully funded U.S. public library operating expenses, according to a new report from Wordsrated, a research data group focused on reading.

I remember 1992 well—it was the year I graduated from high school. It was also, I just learned, the last year in which government (combined local, state, and federal) fully funded U.S. public library operating expenses, according to a new report from Wordsrated, a research data group focused on reading.

In 1992, my public library in suburban New Jersey didn’t have internet access terminals or ebooks, let alone databases, telehealth, social workers, peer navigators, or a community fridge or garden. That’s no slight to the library, which had a dedicated staff and a remarkably robust collection for its size. Many of those services didn’t exist yet at any library.

But it is an indictment of our era’s endemic divestment from public goods that it has been 30 years since our government fully funded library service for its constituents. And in those 30 years, library service has evolved and broadened to the point of transformation.

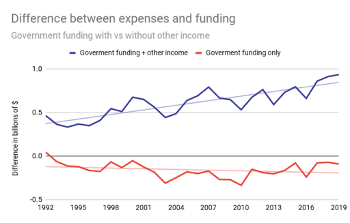

It’s not just local funding that falls short. “Federal government funding has never been lower,” the report says, as of 2019—dropping 13.14 percent since 2014. State government funding peaked in 2001 and declined for years thereafter, only now returning to near that point (in dollars that don’t go as far, owing to inflation).

|

Source: Wordsrated State of US Public Libraries |

Other income from donations, grants, fines, and fees makes up the difference between government allocations and operating budgets, according to Wordsrated. But, of course, many libraries are eliminating fines and fees to lower barriers of access and because they increase inequity. And donations and grants are not necessarily distributed equitably—the former favor those whose user base can afford to contribute, and the latter, those whose library staff have the training and bandwidth to apply. But libraries that need funding most are not likely to have grant writers or constituents with wealth to give.

Meanwhile, the cost to run a library has gone up dramatically: Total operating expenses have doubled since 2016/2017, and nearly tripled since 1992. Two-thirds of that cost is for staff, yet library staff are still paid on average 35 percent below a livable wage for a family of three.

There are other takeaways from the report: While physical visits and print circulation are down, virtual visits and circulation within electronic collections are higher than ever, and this was before the pandemic accelerated the shift to digital. The report also demonstrates, to no one’s surprise, that funding correlates with better service.

The whole thing is worth a read, but I want to focus on this: An entire generation has grown to adulthood without ever seeing their libraries secure, stable, and ready to serve, without having to scramble and cut.

It’s hard to advocate for significantly more resources than were allocated for previous years, especially when it’s not pegged to measurable increases in service. No library leadership team’s case to city hall or millage campaign can reverse decades of systemic loss all at once. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t start trying to turn the tide over time. That starts with tracking, not just year-to-year change, but cumulative impact.

This report is a wake-up call because it puts the bigger picture in one place. Libraries can only benefit from sharing that view with stakeholders.

Let’s set a goal that in 2052, U.S. public libraries will once again be fully publicly funded. And let’s make sure those fully funded budgets include the next 30 years of transformed services, and pay library staff a thriving wage.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!