Where Are We: The Latest on Library Reopening Strategies

In the messy middle of the pandemic, library leaders share how things have changed since March 2020, their takeways, and continuing challenges.

In the messy middle of the pandemic, library leaders share how things have changed since March 2020, their takeways, and continuing challenges

It’s been 10 months, at press time, since those of us lucky enough to be able to work from home left our offices, yet the pandemic continues to rage. While the release of vaccines is cause for hope, living in suspense is challenging, especially for organizations that serve the public. As COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc across the country (and around the world), public libraries are continually recalibrating and reinventing services, plans, and procedures to keep up with a roiling landscape. The pandemic has brought inequities—systemic racism, economic and food insecurity, mental and physical health issues, and digital equity disparities—into sharp focus. Public libraries have been on the front lines, negotiating how to address those ever more urgent issues and provide essential community services while keeping staff and the community healthy.

CONSTANT CHANGES

The pandemic has created an endless loop of ambiguity, where planning is often derailed as the coronavirus surges, mutates, and continues to spread. Kim Porter, director of Indiana’s Batesville Memorial Public Library, made the shift from reactive to proactive planning. Instead of thinking long-term, she focuses on “taking the next right step.” After closing the building for two months in the early days of the pandemic, the library allowed people inside to use its computers and the shared space while social distancing and wearing masks.

Before the pandemic, “I would never have realized the complexity of shutting down 26 libraries and then trying to open them up again,” says Amber Mathewson, director of the Pima County Public Library, AZ. After the March shutdown, “I stated that I would never do a complete shutdown again…and now here we are again on December 21 with only 14 libraries providing curb service only and all other branches closed. What I learned is that it is important to have several plans in place, and…be ready to start [implementing them] at a moment’s notice.”

WHO ARE WE WITHOUT OUR SPACES?

“Never in my 30 years of working in public libraries did I believe we could ever not let people in the buildings for 10 months,” says Lisa Rosenblum, executive director of King County Public Library (KCPL) in Washington. “But we managed to support our staff and the public and create new models of service.” While the building is closed, the library provides curbside services, digital content, and targeted programming to address COVID-related topics such as finding financial assistance and help with job searches. Librarians work directly with residents to provide customized lists of resources and referrals in the patron’s preferred language, either by phone or email. Rosenblum has reconfigured her budget so that 50 percent of all expenditures now go tosupporting digital products to keep up with the demand for remote services. In addition, the library has “sought grants for PPE, Chromebooks, Wi-Fi hot spots, and booster Wi-Fi signals outside of most of our 50 libraries,” says Rosenblum.

Washington State was an early epicenter of the pandemic. As a result, Georgia Lomax, executive director of the Pierce County Library System, explains, “Washington State has been very strict, so we have yet to really reopen.” The library was about to allow the public inside its buildings following the state’s 25 percent capacity limitation, but those plans stopped as cases began to rise again. “This is an opportunity for us to reinforce that libraries and their services are bigger than their buildings,” Lomax says. “Our buildings, like books, are still just one of the tools we use to serve our communities.”

These affirmations can still be accompanied by a feeling of loss, however. “It has been difficult not to be a cooling center in the summer or warming center in the winter or a place for people to just hang out,” says Mary Beth Revels, director of St. Joseph Public Library, MO. “It has humbled me because, in a pandemic, we are not a haven or a safe place for people. That’s always been one of the things I love most about being a public librarian. We’ve had to focus on other ways that we serve our community.”

|

NEXT-STEP SERVICES Libraries are stepping up to navigate the pandemic’s constant changes. Top-bottom: Notary service at St. Joseph PL, fall topiary arranging outdoors at Batesville PL, and Painting at the Pavilion at Batesville |

BUDGET CUTS AND STAFFING LEVELS

Shifts in service have required additional or reallocated resources, even as city and county budgets face dropping property tax revenues and strain to cover testing, treatment, mitigation for schools, and help for the many suddenly unemployed residents Many libraries have had to lay off or furlough employees; often the first to be impacted are part-time staff and pages, and others have seen a reduction in benefits.

Like Rosenblum, Porter has increased the budget line for digital resources, adding Hoopla and other databases to the library’s website, and purchased mobile hot spots to circulate. These adjustments, along with a change in workflow patterns, has led to difficult budgetary decisions, including the need to furlough, lay off, or not replace retiring staff.

During the pandemic, Pima County Public Library had to furlough 260 of its 584 staff members between March and May; most who remained were focused on library infrastructure. While many staff have returned, she is concerned that the library may have another furlough if a shelter-in-place plan goes into effect. “We are doing everything in our power to avoid that, including having staff work half time,” says Mathewson.

The Jemez Springs Public Library, NM, serves a population of less than 2,000 in conjunction with the Jemez Pueblo Community Library. Director Janet Phillips had to cut back on the number of substitute staff because it was too hard to bring them up to speed on the new safety protocols. “Operations became too complex to keep that many people trained while limiting the number of people who entered the building, so sadly, those folks have not worked here during the pandemic,” says Phillips.

In addition to furloughs and layoffs, illness has also had an impact. While most of the libraries interviewed have had staff members contract the coronavirus, no workers have died. All reported transmissions took place outside of the library. Revels is working with the library board to extend the benefits formerly provided under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) and the Emergency Family and Medical Leave Expansion Act (EFMLA) through December 31. The library board is considering continued funding even though the U.S. Congress hasn’t extended the relief laws, she says.

Keeping staff and the community healthy requires personal protective equipment and additional cleaning, all of which comes with a price. “Extra cleaning, face coverings, and intensive air exchange from the outside make energy efficiency literally go out the window!” says Rosenblum.

STAFF WELLNESS

Continuing to work through the collective trauma of a pandemic is draining. Staff, especially those who serve the public directly, face numerous stressors and struggle with physical and mental health concerns. They uphold policies that may be challenged due to political leanings (such as wearing a mask). And they are often working with a reduced number of colleagues, either because of social distancing protocols, a contraction in the workforce due to budgetary reasons, or people getting sick or needing to quarantine. The impact on staff morale, combined with the risk of frontline services, has had some librarians questioning whether to remain in the profession.

So how do libraries maintain morale and staff well-being during a crisis?

For some directors, it’s about maintaining a sense of humor and drawing energy from innovating. Others, like Mathewson and Revels, are using Employee Assistance programs. Some take advantage of services usually provided to patrons, like staff social workers and therapy animals, to help staff cope. Revels canceled the staff day and arranged lunch and staff gifts instead. She uses Zoom dance breaks to buoy spirits.

At the Los Alamos Public Library, NM, staff banded together to create a weekly training and follow-up discussion series. The result, says Director Eileen Sullivan, was that they felt “less isolated and more connected during the early days of the pandemic.” Looking back over the past 10 months, Sullivan says she would “have focused more attention on helping staff handle stress. I was so focused on keeping staff healthy and safe that I did not focus as much attention as I should have on how staff were feeling and coping with the many changes.”

At smaller libraries, with fewer resources, virtual meeting programs like Zoom have been a lifeline. “There are just a few of us, so checking in on each other and not being demanding of strict schedules and deadlines has been important,” says Phillips. “Even when it feels like we aren’t accomplishing much, remembering that we have reinvented how to deliver library services multiple times in the last year is important. The reminder that ‘you are enough’ has been a good one.”

“One of the hardest things as this draws on toward a year is that everyone is tired,” reflects Lomax. “We have to just recognize that, know that we each worry and respond in our own way, and give each other, and our customers, grace.”

|

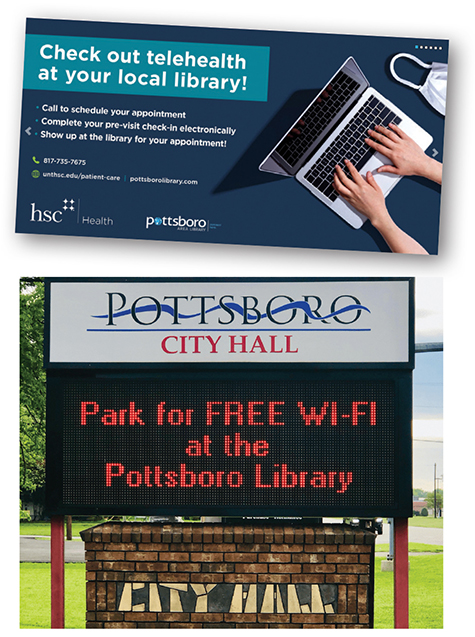

COMMUNITY WI-FI A promotion for Pottsboro PL’s telehealth resources (top); free Wi-Fi service extends to the City Hall parking lot, where residents can connect to it from their cars |

PROGRAMMING PIVOTS

Limitations on travel, group meetings, and in-person socializing have led libraries to provide services in new ways to safeguard public health (see “Reopening Libraries: Public Libraries Keep Their Options Open”). Some innovations, like curbside service, virtual programming, and meetings, are here to stay. In Indiana, Porter held socially distant programs in a a pavilion at a local park during the summer, ensuring that all staff and participants wore face masks, used hand sanitizer, and remained socially distant. Asynchronous outdoor programming such as scavenger hunts and story walks also offer outdoor options when weather permits.

As Zoom fatigue sets in and attendance numbers for virtual programming decrease, take-and-make programs have become popular. These add a hands-on component to virtual programming by providing kits for patrons to pick up at the library to use during a scheduled virtual program. After trying indoor programming (with limited numbers of attendees) in November, Porter transitioned to the hybrid take-and-make model.

“Our Christmas programming became a 12 Days of Christmas Family Take-and-Make bag,” says Porter. “It ended up being a huge hit.” Reflecting on the impact of virtual programming, she says, “It has opened up a whole new world for us. It allows us to connect to other parts of the country, organizations, and people. It has also allowed us the opportunity to collaborate [on] programming with other libraries and community organizations.”

Pottsboro Public Library, TX, which serves a community of 2,500 on Oklahoma’s border, has focused on keeping residents connected. “We now triage the digital needs of our community,” says Director Dianne Connery, who is working with students from the University of Michigan iSchool and Connected Nation on a broadband mapping project. She’s created neighborhood access stations to provide Wi-Fi and uses mobile hot spots so low-income students can take part in virtual learning.

“One of our regular patrons talked about how access to the internet would be the difference between her five children missing a year of school and having those same children thrive,” says Connery. “They do not have internet in their rural neighborhood.… The children need specialized education that the mom doesn’t feel equipped to provide. She earned her GED three years ago and needs job skills. How could we help those children? We were able to refurbish a donated computer from a local business, loan them a hot spot, and provide digital literacy training to the mother.”

The library has maintained a robust mix of virtual and in-person of programs, including e-sports, edible landscaping, using a one-acre lot to create a community garden, coding classes, and exploring virtual reality. Connery secured a grant from the National Library of Medicine and partnered with the University of North Texas Health Science Center to create a pilot telehealth program, repurposing her office as space where the community can receive virtual healthcare.

In Missouri, Revels has increased the number of the library’s contactless services to include scheduled computer appointments, notary services, printing, scanning, and faxing. “At one of our branches the computer is available in a former meeting room, so that branch also allows people to schedule the room for research, meetings involving two people, or a quiet place to study,” says Revels. She anticipates continuing the popular take-and-make programs after the pandemic, as well as the library’s Teen Book Drop, a subscription service developed by her staff. “The teen lets us know what kind of book they like, and staff picks out a couple of books and includes some bookish goodies like crafts or swag,” says Revels. “Everything is packaged in a box for pick up.”

Los Alamos Public Library developed a partnership with the local Senior Center to deliver library materials. It has created pop-up libraries where patrons can pick up activity bags and update or apply for library cards, and it provides online temporary library cards. “We continue to experiment and develop our online programming such as story time on our Youtube channel, Zoom book clubs and Library Conversations series, online LEGO club and crafting programs, and virtual classroom visits,” says Sullivan. Looking to the future, Sullivan expects to offer more outdoor programs, including pop-up story walks.

Some have chosen to scale back, reallocating funding to meet new demands. “We have pared our programs to very basic [ones]: Kindergarten Readiness—Ready, Set, School, and GED, Job Help and ESL,” says Mathewson. “We have put much more money into all of our online databases and resources.”

The move to virtual programming has unexpected upsides, too. Rosenblum has seen increased involvement by older adults since the transition to virtual programming. “Many cannot or choose not to drive in our wet and dark winters,” she says. “More can now participate.”

WHAT WE’LL KEEP

Some of the changes, like curbside service, virtual programs, and an increase in digital resources interest, will be with us long-term. These new models include not only patron-facing services, but changes to library infrastructure.

Utilizing virtual space to host online staff and hybrid board meetings has been a game-changer for KCPL. “We are a big county, and driving 90 minutes, which some staff had to do for a one-hour meeting, in bad traffic, is something no one will miss,” says Rosenblum.

The pandemic has created more opportunities for cross-team collaboration, says Sullivan, encouraging people to work outside their regular boundaries. “Staff who don’t normally present programs are involved in developing and hosting online programs,” she explains. Employees have also led internal training and discussions and created new initiatives—something Sullivan hopes will continue post-pandemic. She plans on continuing to offer online and outdoor programs and to “develop comprehensive strategies and guidelines for utilizing digital technologies to advance our broader mission and values.”

During the pandemic, public libraries began supporting their communities in new ways, something Phillips expects will continue. “I think the movement to bring social workers into libraries will expand to include other services like help with civil justice, business development, food security, and sustainability,” she says. “Libraries exist in the locations [where] these needs are the greatest, and I think they will be great partners in the continued fight for economic and human rights leveling.”

But to continue new offerings may mean rethinking the library’s physical plant. “I think the hardest thing is just that our buildings and parking lots weren’t designed for the new things we are offering—like curbside service or tech access outside,” says Lomax. “We evaluate each location and do our best with their sidewalks, parking lot flows, front entry design, and spaces. People love the speed and convenience of curbside, and I’m sure if we have the opportunity to design or remodel buildings, we’ll incorporate it.”

The Pima County Public Library is planning more outdoor programming and “rethinking our staff workspaces to allow more social distancing in our back rooms,” says Mathewson. “This is a challenge because several years ago, there was a movement to having smaller staff areas to allow for more public space.” She is also reconsidering services and programs. “It may never again be a good idea to have 30 children and their families in a room for story time,” she said. ”We need to look at every program/service and have multiple ways to access those services.”

WHAT WE’VE LEARNED

As the pandemic continues, communication among colleagues and the public is the key to success. “We have increased our social media presence, finding more ways to interact with our community,” says Porter. “We do a simple ‘What are you reading Wednesday.’ Each month we award a winner with Chamber of Commerce bucks.” Sullivan is considering changes to the library’s social media policies “to use multiple platforms to truly connect and communicate with our patrons rather than just push out information about our services and resources.”

The digital divide compounds communication challenges. Phillips reached some of her patrons through the library website and social media but recognized that many people weren’t using those channels. She launched a Neighborhood Connection phone line, where neighbors could call each other to share the news, but it didn’t take off. To her surprise, a robocall she recorded turned out to be popular. In a community too small to have a chamber of commerce, Phillips is now “partnering with the village tech consultant to create a website listing local resources and businesses as a reference tool to supplement the chat sites,” she says.

One thing has become clear—relationships matter, both with community partners and with peers. “These relationships lead to opportunities,” says Connery. “I have a new appreciation for the importance of story telling. Issues like connectivity are dry, but putting a face on the situation promotes understanding and empathy.”

The connection and support of peers is something Phillips intends to maintain once the pandemic subsides. “While national leadership ebbed on many levels, OCLC and the IMLS [Institute of Museum and Library Services] came through with the REALM project, providing us with real data to work with, and the New Mexico State Library stepped up opportunities for training and collaboration,” she says. “I took great comfort in recognizing that library leadership continued to rock.”

While public libraries continue to adapt and innovate, Revels reminds us, “We have to be kind to ourselves.” Porter concurs and reflects that moving forward means “taking the next right step. I have also learned that I need to walk away and take time for myself and recharge. I am a better director, wife, mom, daughter, sister, and friend when I do. I have learned that despite things not going the way I wanted or expected that it will be okay. I am not in control, and I don’t have to be.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!