Closing the Gap in Librarian, Faculty Views of Academic Libraries| Research

In this age of outcomes measurement, many academic librarians are focused—and rightly so—on making sure they best serve students. Yet students are not the only population of end users on an academic campus. Faculty, too, are conduits not only to students but to library users in their own right. As well, studies of faculty attitudes such as Ithaka’s often show that, even as faculty increasingly depend on library-brokered online access to expensive databases and electronic journals, the off-site availability of modern resources may leave many faculty members less aware of the crucial role of the library in their and their students’ workflow.

To study how academic libraries are serving their faculty and how they can improve, LJ partnered with Gale, a part of Cengage Learning, to conduct a joint study of how academic librarians feel they’re serving their faculty clientele—and how faculty members feel they’re being served by their libraries. Examined together, these responses pinpoint where academic libraries can focus efforts to take their service to faculty, as well as students, to the next level. Below is a top-line summary of the findings and some targeted suggestions for acting on them. For much more, see the full report, “Bridging the Librarian-Faculty Gap in the Academic Library.”

Core competencies

Faculty and librarians agree that the most essential service provided by academic librarians is the instruction of students in information literacy.

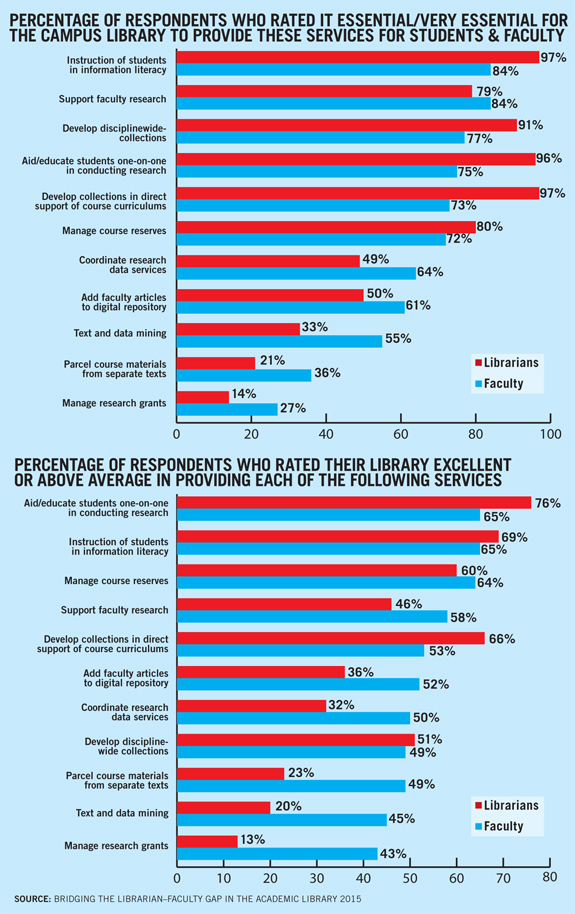

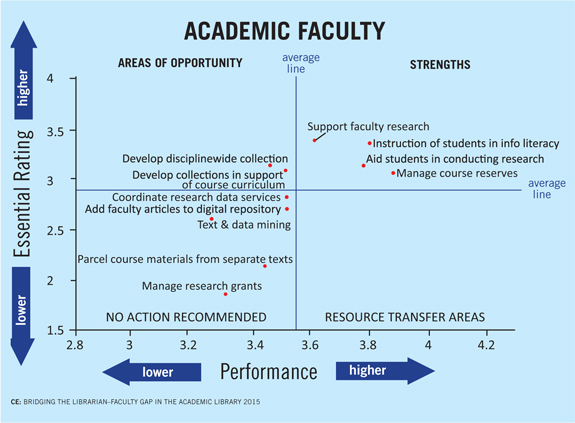

Librarians identified four primary, essential services: “instruction of students in information literacy,” “development of collections in direct support of course curricula,” “aiding students one-on-one in conducting research,” and “development of disciplinewide collections.” By and large, faculty agree that these areas are crucial, but they don’t always agree with librarians’ self-assessment that they’re doing a good job in these key areas. In particular, faculty members’ ratings of “development of collections in support of course curricula” and “development of disciplinewide collections” were low.

Much of the issue boils down to those perennial scarcities, time and money—with both faculty and librarians keenly aware of each other’s constraints as well as their own, even as they wish for more databases, more journals, and more specialized resources in their own areas of study (faculty) and more consultation and involvement (librarians).

Stretch support

The library’s support of faculty research is of utmost importance to faculty—tied for first place—but of secondary importance to academic librarians, coming in a distant fifth.

While agreeing on the primacy of traditional library services, especially instruction in information literacy (along with research), faculty were more likely than librarians to assign greater importance to stretch services such as text and data mining, grant management, and, interestingly, institutional repositories. Contrary to the common narrative that librarians must nag reluctant faculty to participate in repositories, 61 percent of faculty named librarians’ repository services as very important or essential, compared to only half of librarians. Faculty generally gave libraries highest marks in their service to undergrads and second best to service to faculty; service to graduate students came in last.

Also of note, faculty members were more inclined to be happy with librarians’ performance in those stretch areas than were librarians themselves; while librarians ranked their own performance higher than faculty did in core areas, in stretch areas, that reversed, with faculty giving higher marks than librarians.

Space, time main barriers

Collaboration and communication, it turns out, are in the eye of the beholder. Faculty members were far more likely to say they work together with librarians to coordinate course reserves than vice versa: more than half (57 percent) of faculty reported that they consult with the library to coordinate course reserves versus 31 percent of librarians reporting course reserve discussions with faculty.

Even more fundamentally, nearly all librarians think communication between faculty and librarians could be better (98 percent), but less than half of faculty (45 percent) feel the same need.

Areas where more consultation could occur include the development of course reserves and curricula in general.

Many faculty members as well as librarians cited lack of in-person contact as a reason for inadequate communication and collaboration, including distant offices or, for adjuncts, no offices; librarians who don’t leave the library enough and faculty members who no longer feel the need to go there in person. Yet when push came to shove, busy faculty overwhelmingly preferred email as a form of communication with academic librarians, while librarians were more split between email and in-person meetings.

Strategies for change

As far as what it would take to improve that communication, aside from more money, time, and staff members on both sides, the consensus appears to include a broad range of formal and informal mechanisms.

One strand of suggestions from librarians focused on involving librarians in a wide range of existing institutional governance activities: not just departmental meetings but curriculum development committees, professional development days, new faculty orientation, campuswide quality enhancement plans (QEPs), institutionwide grant project committees, etc., as well as getting on the departmental email lists.

A second strand involved creating new mechanisms to connect librarians with faculty both online and off and in both library, departmental, and neutral third spaces. These ranged from the easy to the ambitious and included monthly newsletters sent by the library director; regular faculty/author receptions in the library; yearly workshops about new resources; discipline coffee hours/research roundtables; targeted updates from library to discipline-specific faculty (a suggestion endorsed by several faculty members); research hubs in department centers with staffed hours; a faculty book club; a collection development focus group comprised of faculty members as well as librarians and library staff; and a library-created scaffolded set of modules and tutorials that faculty may easily plug and play, or use in conjunction with library instruction sessions.

Moving up a metalevel, one respondent wanted to create a collaboration to create collaborations: “I wish we had a committee or some sort of group that would be made up of faculty and librarians who could create programs for faculty-librarian partnerships.”

Proximate physical spaces would encourage informal interaction, which would increase the opportunities for faculty members and academic librarians to develop relationships, according to the survey. One respondent suggested a “faculty lounge or club to which librarians would also belong, fostering informal contacts that would enable faculty and librarians to get to know each other.”

An additional factor could be a change in campus culture: some librarians cited a lack of respect for their expertise on the part of faculty, perhaps exacerbated by a lack of faculty status (only 39 percent of librarian respondents worked at institutions that offer faculty status to librarians) or librarians not having doctoral degrees; some faculty members cited lack of helpful attitude or subject knowledge on the part of librarians. As to what mechanism to use to change such an entrenched cultural issue, several suggested asking faculty members who do work closely with librarians to advocate on behalf of the library.

Get the Full Story

To download a free copy of the full report, “Bridging the Librarian-Faculty Gap in the Academic Library,” visit www.thedigitalshift.com/research. To learn more about the findings and hear a librarian and faculty member discuss ways to deepen communication and collaboration between academic libraries and faculty, sign up for the free webcast “Mind the Gap: Find and Fix the Mismatches Between Faculty and Academic Librarians,” which will take place on September 30, at libraryjournal.com/mindthegap.

METHODOLOGY

The faculty survey invite was emailed to a selection of Gale’s faculty list on April 17, 2015, with a second mailing going to additional faculty on April 22. The survey closed on May 5 with 547 respondents. The academic library survey invite was emailed to an LJ list on April 17, 2015. The survey closed on May 5 with 499 respondents.

A drawing to win one of three $100 American Express gift cards was offered as incentive to reply.

Similar sets of questions were asked of the faculty members and academic librarians. Generally, the questions asked both sets of respondents fell along these lines:

- • Essential library resources

- • Rating the library’s performance of those services

- • Extent to which faculty and librarians communicate with one another

- • Method and quality of that communication

- • Communication barriers and suggestions for improvement

- • Educating students about using library resources.

For the complete methodology and both survey instruments, see the full report.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Jodika Gilworth

Hi; the link provided does not seem to lead to the full report, nor have I been able to quickly find the full report on the linked website; has it been moved?

Posted : Apr 03, 2020 10:56

Adrian Jenkins

An excellent report that makes a lot of sense, with some good recommendations for ways forward.Posted : Sep 04, 2015 03:53