In Conversation: The 1619 Project

On Wednesday, November 13, Nikole Hannah-Jones joined Jamelle Bouie for a conversation, moderated by Jelani Cobb, about the making of The New York Times Magazine's 1619 Project.

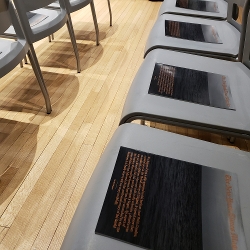

Photos © 2019 Stephanie Sendaula

On Wednesday, November 13, Nikole Hannah-Jones (reporter, The New York Times Magazine), creator of The New York Times Magazine's 1619 Project, joined Jamelle Bouie (columnist, The New York Times) for a conversation about journalism and history, moderated by Jelani Cobb (staff writer, The New Yorker; Ira A. Lipman Professor of Journalism, Columbia Univ.).

The well-attended event was held at Columbia University’s Pulitzer Hall, where attentive students, professors, and journalists gathered to get more insights on the making of the 1619 Project, an issue of The New York Times Magazine dedicated to examining the legacy of slavery. Contributors included historians (Matthew Desmond, Kevin Kruse) and journalists (Jamelle Bouie, Wesley Morris), among others.

Cobb: How do you describe the Project's ongoing appeal?

Hannah-Jones revealed The New York Times Magazine hasn’t seen this much demand since 2008, since the election of Barack Obama. "It's the time we’re [living] in," she said. "White Americans have realized they’re living in the same America that black people have been living in." She explained that black people are looking for data or scholarship to affirm what we've long known or suspected. Bouie also noted the last decade has been an ongoing conversation about race and racism, especially since the shooting of Michael Brown in 2014.

Hannah-Jones revealed The New York Times Magazine hasn’t seen this much demand since 2008, since the election of Barack Obama. "It's the time we’re [living] in," she said. "White Americans have realized they’re living in the same America that black people have been living in." She explained that black people are looking for data or scholarship to affirm what we've long known or suspected. Bouie also noted the last decade has been an ongoing conversation about race and racism, especially since the shooting of Michael Brown in 2014.

Elaborating on the appeal to readers, Hannah-Jones added that it mattered that the 1619 Project was in the "paper of record," giving the Project legitimacy while spurring backlash. Most criticism involved accusing the contributors, especially Hannah-Jones, of being unpatriotic. "The only way you can think this is unpatriotic is if you don't believe black people are fully American," said Hannah-Jones.

Cobb: What was the pitch for the Project?

Hannah-Jones acknowledged it wasn't hard to convince the Times to publish the 1619 Project; rather, it was hard for her to develop a career that would allow her to create such a milestone. In her words, the Project shows that "All across American life, almost nothing has been untouched by slavery." Hannah-Jones described the depth of her research process, which involved rigorous fact checking, along with consulting a panel of historians.

Hannah-Jones acknowledged it wasn't hard to convince the Times to publish the 1619 Project; rather, it was hard for her to develop a career that would allow her to create such a milestone. In her words, the Project shows that "All across American life, almost nothing has been untouched by slavery." Hannah-Jones described the depth of her research process, which involved rigorous fact checking, along with consulting a panel of historians.

Bouie described his contribution to the Project, "What the Reactionary Politics of 2019 Owe to the Politics of Slavery," which details the historical legacy of former Vice President John C. Calhoun, who Bouie considers to be the "intellectual godfather of the Confederacy." In describing the complicated founding of the United States and how discord has been part of the country since the beginning, Bouie brought the discussion up the present day, mentioning backlash from the political right when politicians or policies don't center white, conservative values.

Cobb: What is The Project's intent?

"Everything about our lives was constrained by being assigned a race," Hannah-Jones stated. With the Project, "We were trying to edify people, but in the process, we're edifying ourselves." She described the unique isolation black people experienced; other groups went through a chosen assimilation, whereas black people were forced to renounce their culture. "That stripping down of culture allowed us to create a new one," she maintained.

"Everything about our lives was constrained by being assigned a race," Hannah-Jones stated. With the Project, "We were trying to edify people, but in the process, we're edifying ourselves." She described the unique isolation black people experienced; other groups went through a chosen assimilation, whereas black people were forced to renounce their culture. "That stripping down of culture allowed us to create a new one," she maintained.

The rethinking of history is another one of the Project's goals. Instead of teaching African American history from tragedy to tragedy, Bouie and Hannah-Jones emphasized that how black people resisted the status quo should be taught alongside what they experienced. Their work is also an attempt to rid black history of shame by allowing for a more nuanced retelling, one that moves directly from emancipation in the 1860s to the civil rights movement in the 1960s. The Project has been well received in elementary and secondary schools and in institutions of higher education, and teachers are starting to share how they use it in the curriculum.

Cobb: Are there any improvements you would make to the Project?

Hannah-Jones is proud of the project, which involved eight months of research; however, she would like to address specific subjects, such as education, in the future. For her, "The entire Project is an argument for reparations," and reparation is about restitution. Bouie clarified that in order for Americans to accept reparations, we need to first live in an America that understands and accepts history. His response to those who ask, "When will black people get over slavery?" is to ask, "When will white people get over emancipation?" Considering the question of why immigrants should pay reparations, Hannah-Jones explained that people don't get to decide which parts of American history they claim. "The legacy of slavery harms [black people] the most, but it harms all Americans,” observed Hannah-Jones. "If you don't know how something is built, how can you destroy it?”

What's next?

While the accompanying podcast is on hiatus for the time being, Hannah-Jones is working on new projects, including a 1619 syllabus to be released at a later date.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

allen schade

Since rethinking history is one of the authors goals I'm curious as to why her project fails to mention that of the 13 million Africans who made the passage , all were sold to white slavers by black slave traders. Is this true? If so, doesn't it deserve mention in the discussion about slavery, reparations, etc etc?

Posted : Sep 14, 2020 12:20