Library.Link Builds Open Web Visibility for Library Catalogs, Events

Linked data consulting and development company Zepheira is partnering with several vendors and libraries on the Library.Link Network, a project that promises to make relevant information about libraries, library events, and library collections prominent in search engine results. The service aims to address a longstanding problem. The world’s library catalogs contain a wealth of detailed, vetted, and authoritative data about books, movies, music, art—all types of content. But the bulk of library data is stored in MARC records. The bots that major search engines use to scan and index the web generally cannot access those records.

Linked data consulting and development company Zepheira is partnering with several vendors and libraries on the Library.Link Network, a project that promises to make relevant information about libraries, library events, and library collections prominent in search engine results. The service aims to address a longstanding problem. The world’s library catalogs contain a wealth of detailed, vetted, and authoritative data about books, movies, music, art—all types of content. But the bulk of library data is stored in MARC records. The bots that major search engines use to scan and index the web generally cannot access those records, and aren’t designed to work with MARC formatting, which was originally developed for 1960s and 1970s-era computers. “Catalogs are generally contained in an ILS [integrated library system], and they aren’t visible on the open web,” explained Vailey Oehlke, director of libraries for Multnomah County, OR, which has been working with Zepheira for more than a year. “That’s exactly what Zepheira’s linked data solution hopes to change.” Zepheira has been the Library of Congress’s key partner in the development of the BIBFRAME structured data model for bibliographic description, which LC hopes will eventually supplant MARC. The company was also founding sponsor of the Libhub Initiative, which analyzed how linked data might be used to raise the visibility of libraries on the web and worked to establish consensus within the field regarding best practices, laying the groundwork for Library.Link. Companies and services currently involved with the new initiative include SirsiDynix, Innovative Interfaces, EBSCO Information Services, NoveList, LibraryAware, Counting Opinions, and Atlas Systems. Zepheira copies a partner library’s catalog, converts records into the structured BIBFRAME format, and then hosts these BIBFRAME records in the Library.Link global, shared content distribution network designed for large-scale web ingest. The library’s original catalog remains intact—as Zepheira’s VP of Product Management Jeff Penka explained, the process is “non-destructive to current data and systems.” And content updating—currently every couple of weeks—ensures that data hosted by Zepheira is current, reflecting titles that have been recently acquired or weeded by the library, for example. Creative Commons licensing—requiring attribution to the library—is also added to each record, ensuring that service providers such as Google and Microsoft know where the data came from and what companies are allowed to do with it. Collections are one of the library’s largest assets, but also one of the most invisible on the web, Penka said. A library website might contain a few hundred discretely indexable pages, “but imagine if every individual page in the library catalog was able to be indexed. Now you’re talking about hundreds of thousands, or millions more.” Separately, libraries add key descriptive information to their “Local Link Graph” domain on the Library.Link network, such as branch locations and operating hours, library services, links, upcoming events, staff listings, and more. Zepheira structures this data for ingest by search engine web crawlers as well, using schema.org and Facebook Open Graph structured data markup. In partnership with Zepheira, SirsiDynix in January launched “BLUEcloud Visibility,” and Innovative Interfaces Inc. in March launched “Innovative Linked Data,” both of which integrate these processes with their customers’ existing ILS or LSP (library services platform). “We’ve been talking about this for years—how do we help libraries…put their content online and make it visible?” said Eric Keith, VP of global marketing, communications, and strategic alliances for SirsiDynix. According to some “back of the envelope math,” Keith estimated that only .003 percent of content searches originate on library websites and catalogs, compared to the vast majority that originate on the open web. “We know that a huge percentage of searches do not involve the library, so if we could make that content from libraries show up, it could be a sea change as far as the visibility of libraries,” Keith added.

Linked data consulting and development company Zepheira is partnering with several vendors and libraries on the Library.Link Network, a project that promises to make relevant information about libraries, library events, and library collections prominent in search engine results. The service aims to address a longstanding problem. The world’s library catalogs contain a wealth of detailed, vetted, and authoritative data about books, movies, music, art—all types of content. But the bulk of library data is stored in MARC records. The bots that major search engines use to scan and index the web generally cannot access those records, and aren’t designed to work with MARC formatting, which was originally developed for 1960s and 1970s-era computers. “Catalogs are generally contained in an ILS [integrated library system], and they aren’t visible on the open web,” explained Vailey Oehlke, director of libraries for Multnomah County, OR, which has been working with Zepheira for more than a year. “That’s exactly what Zepheira’s linked data solution hopes to change.” Zepheira has been the Library of Congress’s key partner in the development of the BIBFRAME structured data model for bibliographic description, which LC hopes will eventually supplant MARC. The company was also founding sponsor of the Libhub Initiative, which analyzed how linked data might be used to raise the visibility of libraries on the web and worked to establish consensus within the field regarding best practices, laying the groundwork for Library.Link. Companies and services currently involved with the new initiative include SirsiDynix, Innovative Interfaces, EBSCO Information Services, NoveList, LibraryAware, Counting Opinions, and Atlas Systems. Zepheira copies a partner library’s catalog, converts records into the structured BIBFRAME format, and then hosts these BIBFRAME records in the Library.Link global, shared content distribution network designed for large-scale web ingest. The library’s original catalog remains intact—as Zepheira’s VP of Product Management Jeff Penka explained, the process is “non-destructive to current data and systems.” And content updating—currently every couple of weeks—ensures that data hosted by Zepheira is current, reflecting titles that have been recently acquired or weeded by the library, for example. Creative Commons licensing—requiring attribution to the library—is also added to each record, ensuring that service providers such as Google and Microsoft know where the data came from and what companies are allowed to do with it. Collections are one of the library’s largest assets, but also one of the most invisible on the web, Penka said. A library website might contain a few hundred discretely indexable pages, “but imagine if every individual page in the library catalog was able to be indexed. Now you’re talking about hundreds of thousands, or millions more.” Separately, libraries add key descriptive information to their “Local Link Graph” domain on the Library.Link network, such as branch locations and operating hours, library services, links, upcoming events, staff listings, and more. Zepheira structures this data for ingest by search engine web crawlers as well, using schema.org and Facebook Open Graph structured data markup. In partnership with Zepheira, SirsiDynix in January launched “BLUEcloud Visibility,” and Innovative Interfaces Inc. in March launched “Innovative Linked Data,” both of which integrate these processes with their customers’ existing ILS or LSP (library services platform). “We’ve been talking about this for years—how do we help libraries…put their content online and make it visible?” said Eric Keith, VP of global marketing, communications, and strategic alliances for SirsiDynix. According to some “back of the envelope math,” Keith estimated that only .003 percent of content searches originate on library websites and catalogs, compared to the vast majority that originate on the open web. “We know that a huge percentage of searches do not involve the library, so if we could make that content from libraries show up, it could be a sea change as far as the visibility of libraries,” Keith added. Search evolution

This project, and the BIBFRAME initiative more broadly, comes at a time when search engines have been undergoing a sea change of their own. Readers have probably noticed Google's "Knowledge Graph" cards, which have been popping up alongside search results involving popular topics for a few years. A search for a current artist, such as Beyoncé, will result in a panel with a bio, a summary of recent news, lists of upcoming tour and event dates, images, song and album lists, links to official social media profiles, and more. Users no longer have to scroll through summaries of pages that may or may not have the information for which they were looking. Drawing current information from multiple different websites, these panels are an early example of the power of structured, linked data. Early search engines, such as AltaVista, worked by using web crawlers to build an index of the entire web that users could then search. Retrieving the most relevant pages was somewhat dependent on the user's ability to narrow results using advanced search options and Boolean operators. Google revolutionized search in the late 1990s with an algorithm that, essentially, used a citation model. The engine still used web crawlers to build an index of websites, but the algorithm ranked site relevance by analyzing which sites had the most links pointing back to them from around the web. The PageRank algorithm has been refined over the past two decades, but for years Google and other Internet search providers have been working on the next major Internet evolution—building a web of data that computers can process, defining entities and identifying relationships, or "links," between those entities. In their May 2001 Scientific American article "The Semantic Web," Tim Berners-Lee, James Hendler, and Ora Lassila envisioned a future in which, "the Semantic Web will bring structure to the meaningful content of Web pages, creating an environment where software agents roaming from page to page can readily carry out sophisticated tasks for users. Such an agent coming to [a medical clinic's] Web page will know not just that the page has keywords such as "treatment, medicine, physical, therapy" (as might be encoded today) but also that Dr. Hartman works at this clinic on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays and that the script takes a date range in yyyy-mm-dd format and returns appointment times." Librarians have been hearing about the promise of the semantic web and linked data ever since. But these concepts are no longer theoretical. For a literary example, Google's Knowledge Graph can use a structured data source such as Wikidata to establish that Jane Austen was a novelist who wrote books including Pride and Prejudice and Emma, and then use another structured data source, such as IMDb, separately to determine that these works have since been adapted many times over as movies and miniseries, including related, modern adaptations such as Clueless. Pulling information from multiple sites, the Knowledge Graph can display a fairly thorough summary of information about Austen, including images, a brief bio, famous quotes, book covers and links to books, as well as links to movies and shows based on those books. The official website of a contemporary artist, performance venue, restaurant, or business, etc. will also be regarded as a trusted source of information by the Knowledge Graph. If webmasters use structured data markup such as schema.org—created and supported by Google, Yahoo, Microsoft, and Yandex—search engines will be able extract information such as upcoming events, recent releases, or mapped locations, hours of operation, and menus, and display that information in the Knowledge Graph card on a search results page. If Google can determine the location of the user conducting the search via IP address or smartphone geolocation, then these results are tailored and mapped to that location. Of course, the data involving 19th and 21st century superstars like Jane Austen and Beyoncé is relatively easy to retrieve and confirm. So is information from official websites of restaurant chains, major concert and sports venues, and other corporate entities currently using structured data on their websites.New connections

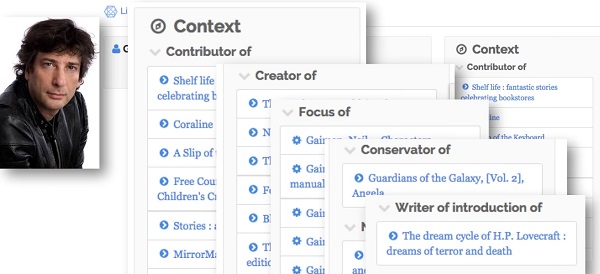

By hosting catalog records, and information about library locations and events as structured data, the Library.Link network will present libraries—individually and in aggregate—as a major source of high-quality, vetted linked data that Google and other search engines can use to improve search results and expand features like the Knowledge Graph cards. In turn, as the sources of this high-quality data, participating libraries and library content will surface more prominently in relevant open web searches, based on the location from which people conduct their searches. Penka described how a library's records of a popular author, such as Neil Gaiman, would work in this scenario, once Library.Link converts a MARC record catalog to BIBFRAME and hosts it on the open web. "In the context of linked data [Gaiman] is a person," he said. "But if you actually dig in on Neil, he’s also a contributor [to anthologies], a [content] creator, a focus [of interviews, criticism, and interpretation], a conservator, a narrator [of audiobooks]…and this information all came from MARC data. All of this rich information basically means, as we’re teaching the web how to consume this...there is no such page like that in the catalog [showcasing the entirety of his work], but we’ve taught the web how to get to over 250 other items in the catalog." Partnerships with services such as EBSCO's LibraryAware and NoveList aim to enhance the richness of that data. The new NoveList Select for Linked Data service, for example, adds metadata such as subject headings, genres, tone, pace, writing style, and appeal terms to BIBFRAME catalog records in the Library.Link network, generating readalikes and other information to help readers explore a library’s collection. “In 2010 we started enriching library catalogs with our content so that readers who were using the library’s most frequently consulted resource could see and find the content that would help guide them to their next book,” said NoveList cofounder and general manager Duncan Smith. “Today, when…a search for information, or a book, or an event, or workshop [usually starts on the open web] we had an opportunity with Zepheira…to make libraries more visible, and communicate their value.” Oehlke said that the early growth of Library.Link may be slow going, with results improving as more libraries add records to the network. But Multnomah was already seeing results when she discussed the project with LJ a few weeks ago. “Since we published the data last year, we’ve seen over 23,000 visits to our catalog” originating as open web searches, and 20 percent of those visits were from mobile devices. “I think [the project] has a ton of wonderful potential,” she said. “I have every expectation that it will pick up as more libraries sign on.”

Add Comment :-

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

TECHNOLOGY

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing