MacArthur Fellow Lynda Barry Shares the Secrets of Her Creative Recipes

With Making Comics, Lynda Barry brings four decades of cartooning experience to her delightfully unorthodox pedagogy. In a recent phone interview with LJ, the newly minted MacArthur Fellow revealed a few of the secrets of her creative recipes. Here’s what she had to say.

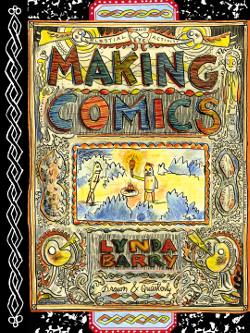

With Making Comics (Drawn & Quarterly; starred review, LJ 12/19) Lynda Barry brings four decades of cartooning experience to her delightfully unorthodox pedagogy. In a recent phone interview with LJ, the newly minted MacArthur Fellow revealed a few of the secrets of her creative recipes. Here’s what she had to say.

With Making Comics (Drawn & Quarterly; starred review, LJ 12/19) Lynda Barry brings four decades of cartooning experience to her delightfully unorthodox pedagogy. In a recent phone interview with LJ, the newly minted MacArthur Fellow revealed a few of the secrets of her creative recipes. Here’s what she had to say.

Making Comics is your fourth book on process. Do you see these titles as building on one another?

Making Comics comes out of my experience of having taught these exercises in classes and workshops for seven years. I wanted to write down the recipes and offer them to a more general audience, to help those who have given up drawing because they feel they can’t draw a hand or a nose, for example.

If you imagine Bart Simpson or Charlie Brown with a hyperrealistic nose, that would look weird, right? Essentially, you can think about using the same lines to draw that we use to make numbers and letters. So, Making Comics is intended as an alternative to a theory-heavy approach to teaching comics—it utilizes what you have available immediately and gets you started drawing right away.

Your focus in this book seems to be more on the writerly elements of cartooning—plot, character, setting—and how images and words are inextricably linked. Is this an articulation of your own intuitive process and creative challenges, or do you consciously work this way? Or is it something entirely different?

The exercises in this book are exactly how I work! The writing and drawing aren’t separate at all—they’re an intuitive process that comes together. I never script a story before I make a comic strip—I let them meld together. When we’re young, writing and drawing naturally happen together, but then they get split apart educationally around the first grade.

In college I had a teacher, Marilyn Frasca, who treated different creative arts exactly the same—it didn’t matter the form, whether play, sculpture, or comic, as long as the living core of the work, its basic idea, was the same. I took that concept on in my own work at 19 or 20 and ran with it.

My greatest challenge is time! There’s an idea that you can start and stop your work anytime. But you shouldn’t—it’s like watching a play, you don’t press pause to go get a snack in the middle. When I begin a four-panel comic strip, for instance, I’d ideally have four hours to complete it. That’s a lot of time! The creative process has a beginning, middle, and an end, and you have to make time for all of it.

At one point in the book you reference American Italian cartoonist Ivan Brunetti as an inspirational teacher. How do you use his work in the classroom?

At one point in the book you reference American Italian cartoonist Ivan Brunetti as an inspirational teacher. How do you use his work in the classroom?

Brunetti’s Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice is the best that exists—it has simple, elegant, basic instruction on how to draw a person who can move and do things. No stick figures! Stick figures can’t move or do things or even eat! With the Brunetti style of figure drawing—big head, little body, wiggly arms that move like noodles—drawings can move immediately. Some student artists do things that make it hard for a story to creep in—Brunetti’s approach to character creation helps the story arrive.

How do you envision Making Comics being used by budding cartoonists or those working in fits and starts? The instructions in the exercises here are for classroom or home use—I see each activity as a recipe, with a timed exercise and a list of the tools you need. I wanted readers to be able to say purposefully, "Here’s where I begin and here’s where I stop." Vagueness keeps us from working, so knowing how much time and space I have to do something is helpful. A story needs time and space to show up—the least important part is a starting idea.

How do you advise students who are stuck on one topic or theme or who might be tired of writing about the same thing?

I find that I don’t really run into that problem. The way I’m teaching is meant to get you unstuck by purposefully including elements that are beyond your control. For instance—I’ll take a bunch of cards, labeled with nouns, settings, and so on, and then roll the dice. When I pull the cards, I have a combination of things to incorporate into a story. It’s important to try to keep your own choice out of it as much as you can. Otherwise, there’s too much pressure on your idea and it doesn’t have a chance to present itself to you. Anything that’s worth writing about or drawing—there’s always something fighting against it.

Congratulations on the MacArthur genius grant! What are your designs for using the award?

I’m delighted, obviously! I’m going to use the award to spend more time studying the point in people’s lives in which drawing and writing split. I’m also working on a book from that experience. I’ve been doing this with my graduate students at UW-Madison through a program called "Drawbridge," in which my students work with kids as coresearchers.

When little kids are drawing we tend to respond one of three ways—we’ll teach the kids how to make a cow, let them do their own thing and say, "that’s fantastic and amazing!" without engaging, or we show basic indifference. Parents, even pre-K teachers, will often apologize about how they draw—so...if drawing is a language, and the adults are too scared to speak it, how will kids learn to do it?

I like to explore mutual engagement, in which adults and kids both benefit from one another, by having adults copy kids while they’re drawing in real time. Three to five year olds have a living relationship with writing and drawing, and drawing with them and observing them has always gotten me out of ruts. The book will be about drawing with kids in a way that is of mutual benefit rather than about teaching kids to draw.

When you draw with a child, you can put the marker in your hand and let them direct it—they have information to share with you! Let it flow rather than controlling it. Let them use you as a drawing tool.—Emilia Packard, Tokyo, Japan

This article originally ran in Library Journal's December 2019 issue

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!