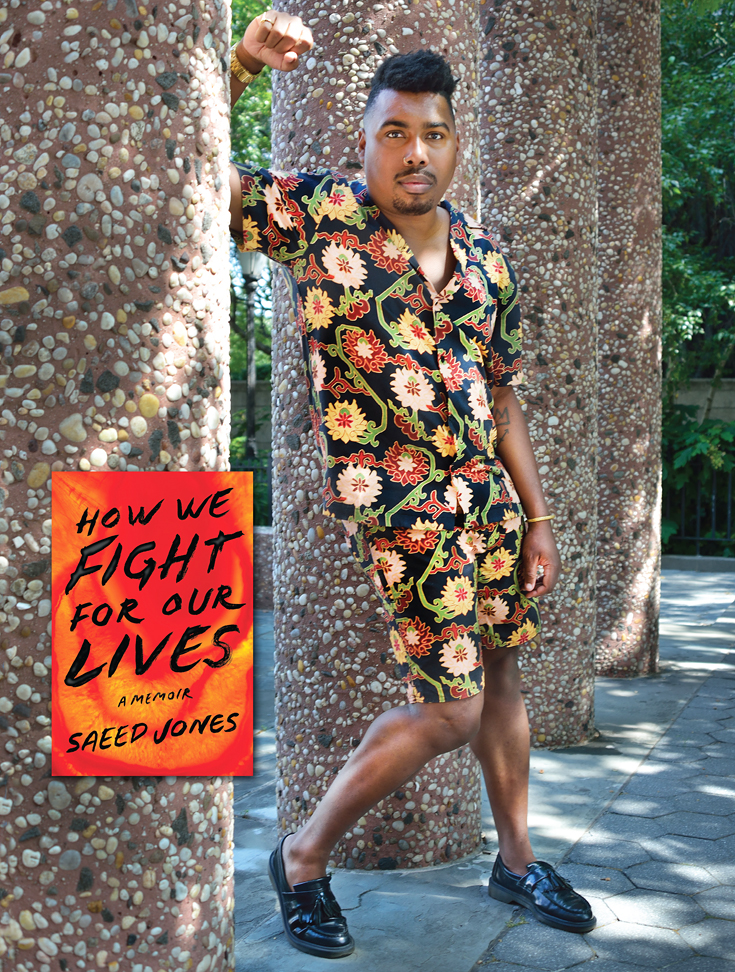

Saeed Jones on the Power of Writing | Editors' Fall Picks 2019

In July, poet and writer Saeed Jones spoke with LJ about his latest work, How We Fight for Our Lives: A Memoir. Jones is also the author of the award-winning poetry collections Prelude to Bruise (2014) and When the Only Light Is Fire (2011).

In July, LJ spoke to poet and writer Saeed Jones about his latest work, How We Fight for Our Lives: A Memoir. (See the editor’s pick, LJ 8/19, and starred review in that same issue.) Jones is also author of the award-winning poetry collections Prelude to Bruise (2014) and When the Only Light Is Fire (2011).

How would you describe your book?

I think a lot of people in this country, men in particular, have never really sat with the question "Why am I like this?" As we see more and more lately, failing to answer that question is perilous, not just for ourselves but for anyone in our path. I’m a joyful person and strive to embrace opportunities for joy as much as I can, but I’m inherently driven by rage. I am disgusted by how this country lies to us about what it is doing to us. I am disgusted by how effective the lies are, and how they eventually lead us into self-deception.

Growing up in Texas, people didn’t have to call me a "faggot," because I already believed I was a "faggot" based on what I was observing around me. No one had to call me "nigger" for me to hear it ringing in the air like wind chimes. As much as this book is my coming-of-age story as a gay black man raised in the American South by a single mother, it is also my attempt to excavate the reasons I’ve come to think of life as a fight. As it turns out, I have some damn good reasons to keep my fists up.

Growing up in Texas, people didn’t have to call me a "faggot," because I already believed I was a "faggot" based on what I was observing around me. No one had to call me "nigger" for me to hear it ringing in the air like wind chimes. As much as this book is my coming-of-age story as a gay black man raised in the American South by a single mother, it is also my attempt to excavate the reasons I’ve come to think of life as a fight. As it turns out, I have some damn good reasons to keep my fists up.

Have your experiences as a poet informed your long-form writing?

Absolutely. Poetry makes me a very slow prose writer. With poems, I revise as I write each line. I don’t move on to the next line until I’m satisfied. By the time I’ve finished writing a poem, I’ve probably rewritten it from the beginning 30 or 40 times. I tried writing the memoir this way, trying to perfect the language as I was generating the material. But even after I came to my senses and stopped trying to write each chapter line by line, the music found me. It’s just there—both in me and in what I write.

You write about change and vulnerability; what was the most difficult time of your life to talk about?

In 2011, the night before Mother’s Day, my mother had a heart attack. She died a few days later. Time just unspooled. I was sleepy all the time and often felt like I was turning into fog. Writing about it was painful and difficult because it felt like I was burying my mother all over again.

There is a brutal finality to writing about a loved one’s death. It’s the only time I’ve ever cried while writing. I actually experienced several panic attacks. A friend had to come and get me. But my mother was a fighter and I am her son. So, I kept trying. I eventually wrote that section of the book very quickly, both to keep from censoring myself but also because I wasn’t sure how much longer I could sustain the energy.

How did you approach writing about family secrets?

I don’t believe in family secrets. There is either accountability or there isn’t. I called my grandmother a few times while writing the book and assured her that I would do my best to show all the nuances of our relationship and how we have both changed over time; but what happened happened. I also let all the family members who appear prominently in the book read the manuscript before the galleys went out. I really appreciate the phone calls we had after they finished it.

What do you hope readers take away from your book?

Already, I’ve received several notes from readers, quite a few of them black gay men, saying that they recognized parts of themselves in my story: "I have said that exact same thing to myself! I remember thinking that, too!" They often note that the self-recognition is both a bit painful and comforting.

I want people to understand that they are not alone in their experience. When we think we are the only one going through whatever we’re going through, we are imperiled. I believe you can save someone’s life by honestly explaining how you have been where they are and that you’re still here. Your testimony can be a reason for someone to remember that they still have some fight left in them.

How did you know when your memoir was finished?

Honestly, I wouldn’t be entirely shocked if my editor called me tomorrow and said that we need to do one more draft.

Photos ©2019 William Neumann

This Q&A was originally published in Library Journal's August issue as part of the Editors' Picks feature, "Fall Fireworks."

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!