Materials Mix: Investigating Trends in Materials Budgets and Circulation

Fifteen years ago, Library Journal launched its first annual book-buying survey of public libraries nationwide. Although materials budgets were referenced, the report focused almost exclusively on book budgets and book circulation.

This year, in long-overdue recognition of what today’s collections really look like—and what the reports have been covering for years—the entire effort has been rebranded the materials survey. Further distancing itself from its roots, the new survey will leave comparison of operating costs to LJ’s annual budget survey and concentrate exclusively on budget and circulation trends for the wide array of materials in public libraries today.

The materials breakdowns reported by this year’s respondents will come as no surprise to anyone who has set foot in a public library recently. Though materials budgets remained flat, averaging $765,000 and veering from $24,000 overall for libraries serving populations under 10,000 to nearly $4.5 million overall for libraries serving populations of 500,000 or more, total book budgets—averaging $449,800—have fallen.

Some bright news for the print faithful: the slip averaged only 0.8 percent, and half of LJ’s respondents saw no change in book budgets at all. Stepping back, though, presents a different picture. Book budgets fell on average in every region but the South, and in some libraries—those serving populations of 100,000 to 499,999—the cuts were big, averaging more than four percent.

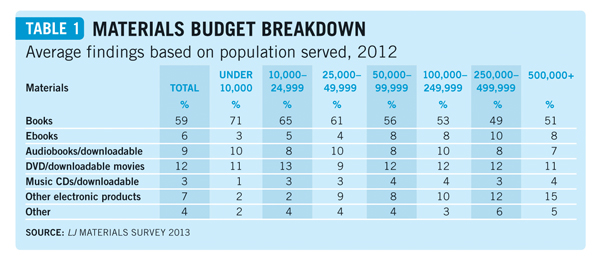

What’s more, books averaged only 59 percent of materials budgets, down from 61 percent last year and from the ten-year high of 68 percent in 2005 and 2006—a nearly ten-point drop. At libraries serving populations of 500,000 or more, books accounted for only about half the materials budget.

Interestingly, even as total book budgets tumbled, adult fiction book budgets inched upward, a consequence of both the continuing emphasis on in-demand titles (often fiction) and the loss of nonfiction readers to the Internet, as already reported in this survey. In 2003, adult fiction comprised 45 percent of the adult book budget, but that figure rose to over half in the following year and has been rising ever since. This year, fiction averaged 60 percent of respondents’ adult book budgets and around 70 percent at libraries serving populations of 25,000 and under.

The budget gets remade

If book budgets are down, even as materials budgets hold steady, where is the money going? To media and ebooks, of course (see “Materials Budget Breakdown,” at right). This year’s respondents pegged media—that is, audiobooks, DVDs, and music CDs and their downloadable counterparts—at 24 percent of the materials budget, up from 20 percent last year and double the percentage ten years ago. (For accuracy, let’s note that downloadables weren’t part of the mix in 2003, and the survey was not yet asking about music CDs.) DVDs/downloadable movies were the big media contenders, taking 12 percent of the materials budget on average, while music CDs/downloadables claimed only three percent.

Ebooks, offered by 87 percent of respondents (up from 79 percent last year), now take a six percent bite from the materials budget. That’s up from one percent in 2009, evidence that ebooks have secured a place in public libraries despite big-publisher resistance.

Fully 62 percent of respondents boasted increased ebook budgets, with only two percent suffering a decrease, resulting in an eye-opening 32 percent increase overall. Libraries serving populations under 10,000 saw the smallest increases—only about five percent on average—while those serving a range of populations, from 10,000 to 249,999, are now embracing ebooks fervently, with budget leaps averaging 35 percent to 45 percent.

While ebooks are booming, other electronic products, including reference, are not. These products accounted for only seven percent on average of respondents’ materials budgets, having slid downward since 2008, when they hit a ten-year high of ten percent. Evidently, libraries are saving themselves a bundle by, for instance, cutting out high-priced databases that just don’t get the use that had been expected.

Circ’s up

Book budgets may have gone south, but book circulation remains healthy. While last year’s respondents surprised us by reporting stalled circulation after a ten-year surge, this year’s respondents saw book circulation rise 1.6 percent on average, with circulation looking up in every size library but those serving populations of 10,000 to 24,999. The biggest gains were among libraries serving populations of 250,000 to 499,999, which recorded an overall increase of 3.7 percent.

As a percentage of total circulation, book circulation was highest at rural libraries (67 percent) and lowest at suburban libraries (60 percent) and, interestingly, exactly the same at independent libraries and library systems (63 percent). Adult books accounted for 53 percent of book circulation, with children’s books and YA books claiming 38 percent and nine percent, respectively. Compared with last year, though, adult book circulation lost a few percentage points to books for children and young adults. Who says kids don’t read?

Fiction continues to outstrip nonfiction in public library circulation, averaging 65 percent of the take. Within fiction, mystery still reigns supreme, cited by 99 percent of respondents among the top five fiction circulators, though it’s not quite as strong at urban libraries (see “Top Fiction and Nonfiction Circulators,” at right).

General fiction and romance follow, cited by 84 percent and 76 percent of respondents, respectively. Romance is nowhere near as popular among rural readers, however, who instead cotton to Christian and YA fiction. Alas fans of Dante and William Gass, the tilt toward popular literature is evidenced by the failure of literary fiction and the classics to make the top ten fiction circulators.

Recent trends in nonfiction circulation are holding steady. Five years ago, cooking took over the top spot from health/medicine, and its position is even stronger now. Since 2008, the number of respondents citing cooking among the top five nonfiction circulators has risen from 59 percent to 79 percent on average, and it dominates in all types of libraries—urban, suburban, and rural. (Is it all those hot chefs?)

Health/medicine (biggest in suburban libraries), how-to/home arts (biggest in rural libraries), and arts/crafts/collectibles (also a rural phenomenon) take the next three slots. Business/careers continues to ease downward, a perhaps encouraging sign. Less encouraging for the civic-minded is the fall of current events/politics, a rising star since 2003 that stumbled badly last year; the number of respondents claiming it as a top nonfiction circulator fell by half. This year it fared no better. Perhaps we’re all just sick of politics.

What really circs

What really circs

At 63 percent overall, books still grabbed the lion’s share of circulation. DVDs/movie downloadables—biggest at urban and at independent libraries—come in next at 21 percent overall.

Audiobooks/downloadables and music CDs/downloadables are relative small fry, averaging seven percent and four percent of circulation, respectively. These media are overshadowed by big brother DVD in other ways. While the circulation of DVDs/movie downloadables increased by 3.4 percent, the circulation of music CDs/downloadables fell by about the same percentage. The circulation of audiobook/downloadables remained flat.

At the moment, ebooks stake a claim to only three percent of total circulation, but watch out. This year’s respondents reported that ebook circulation soared 47.2 percent overall, with the largest libraries—those serving populations of 250,000 or more—reporting increases closer to 70 percent. Even the smallest libraries, serving populations under 10,000, saw ebook circulation increase by 16.5 percent on average. Most of those ebooks are fiction, which accounts for 80 percent of ebook circulation.

The ebook effect

In the end, will ebooks help boost public library circulation or help knock it down? The jury’s still out. Nearly one in five of this year’s respondents saw circulation decrease, and though budget cuts, closed branches, longer loan periods, and improved school library services were among the expected reasons, Mary Cronin, Madison Library, NH, made a comment echoed by many: “More patrons with reading devices are opting to purchase content rather than borrow it from the library.”

Cronin’s comment affirms a long-standing concern, while Jackie Davis, Anderson Public Library, IN, offers more context about the challenges ebooks present for public libraries: “The way people browse and check out ebooks vs. physical books is very different. It’s very easy to pull multiple books off the shelf to check out and take home to thumb through. The discovery and browsability of ebooks is abysmal.” Davis’s library limits the number of ebooks users can check out and generally denies renewals, which has a further impact on circulation.

Finally, though they’re not part of the circulation question, what about apps? They’re just catching on, with only 15 percent of this year’s respondents saying that their libraries offer them. Still, while no libraries serving populations under 25,000 boasted apps, 42 percent of libraries serving a population of 500,000 did, and apps remain an important new entry in the materials mix to watch. The most popular apps are Boopsie, Freegal, OverDrive, and BookMyne.

Self-published books

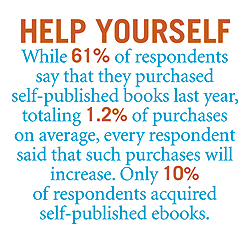

Smashwords and CreateSpace. E.L. James’s Fifty Shades of Grey and Alan Sepinwall’s The Revolution Was Televised. Self-published books are in the news—and in public libraries nationwide. Among this year’s respondents, 61 percent said that their libraries purchase self-published books in print, with the number bought last year averaging 1.2 percent of total book purchases. Of respondents whose collections include such titles, not one expected purchases to decrease.

So far, so good, but let’s point out a few negatives. Of the respondents who haven’t purchased self-published books in print, only 25 percent said that they would likely do so in the coming year, so growth opportunities aren’t as big as one might expect. Furthermore, only ten percent of respondents—and those only at libraries serving populations of 50,000 and up—said that their libraries had purchased self-published ebooks. That’s surprising, given the tremendous buzz such titles have been generating and the interesting alternative they might have offered libraries shut out of big-publisher titles.

Although perhaps not that surprising. When asked what genres their libraries favored in self-published titles, respondents overwhelmingly cited local authors (58 percent) and local history (53 percent). As Anderson Public Library’s Davis says, “We purchase some self-published titles, but only if there is a compelling reason, and we almost never purchase nonfiction (other than poetry) unless there is a community focus.”

Furthermore, by far the leading source of information about self-published books, ebook or print, is word of mouth—what the butcher, baker, and candlestick maker have to say about a book, not professional journals or TV celebrities. For many public libraries, then, these books are very much a local phenomenon.

Marketing the mix

Marketing the mix

With all the selection and management tools now available to librarians, from vendor-generated lists to CollectionHQ, are librarians looking at the rich array of books and ebooks, DVDs, and downloadable audios in their collections and starting to think of their work as more promotion than collection development? Not all of them. Says Inese Gruber, Windham Public Library, ME, “Promotion is ongoing, but collection development is still vital to reflect our community’s character.”

In fact, some librarians find that those tools actually free them up to focus more fully on collection building. Says Nancy Messenger, Sno-Isle Libraries, WA, “We have implemented CollectionHQ in the past year, and while the product focuses on moving the collection through circulation, it also has given our staff the tools they need to keep the collection refreshed and relevant to the communities they serve.”

Yet other librarians—about a third of LJ’s respondents—now see promotion as a large part of the job. Centralized selection, of course, has meant that many librarians have redirected their energies to talking up the collection; the need to buy mostly popular materials to meet demand has compelled others to turn from fretting over purchases to connecting what’s bought with users. Still others argue that marketing is now a defining aspect of library work.

“Librarians have everything to gain by working at salesmanship,” insists Celeste Steward, Alameda County Library, CA. “Bookstores are going away, yet people still like to browse and talk about books. I find it an exciting challenge—how will we promote without physical format? What will collection management mean in the digital age?”

As Steward points out, social media today allow librarians to push their collections in a really big way. So if you’re intimidated by Twitter or Pinterest, get over it. Tweeting your latest order won’t overwhelm the holds list, and managing a social media campaign might be the best thing you’ve done for the library. Today’s collections are richer than ever and diversifying quickly, and as ever-rising circulation suggests, users out there want to know.

- The Library Materials Survey was emailed to approximately 3,500 LJ newsletter subscribers on November 16, 2012. A reminder went out to non-responders on December 7.

- A drawing to win an iPad mini was offered as incentive.

- The field closed on December 12, 2012.

- A total of 175 U.S. public libraries responded.

- The data was weighted by population served to even out fluctuations in respondent sample sizes in each group. Weighted averages shown for total sample results only. Data appearing for specific population groups is unweighted.

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing