2018 School Spending Survey Report

Open Music Library Combines Free and Subscription Databases

Academic database and streaming media publisher Alexander Street is beta testing the Open Music Library (OML), a new online resource that will eschew database paywalls, enabling non-subscribers to discover and use high-quality open access and public domain content from contributors such as the Library of Congress (LC) and the British Library (BL), while offering subscribers a seamless experience discovering and using free and for-fee content together.

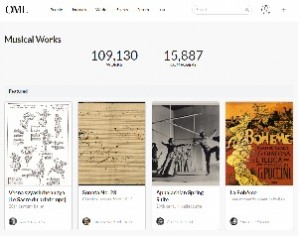

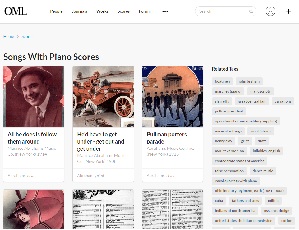

Academic database and streaming media publisher Alexander Street is beta testing the Open Music Library (OML), a new online resource that will eschew database paywalls, enabling non-subscribers to discover and use high-quality open access and public domain content from contributors such as the Library of Congress (LC) and the British Library (BL), while offering subscribers a seamless experience discovering and using free and for-fee content together. “Within the marketplace as a whole, there seems to be this almost religious schism between the open access, ‘all information should be free’ advocates and vendors that believe information should be behind a paywall,” said Stephen Rhind-Tutt, president of Alexander Street, a ProQuest company. “Most faculty and students don’t share in that schism. They want the best information, no matter where it’s to be found.” Rhind-Tutt pointed to Wikipedia and the New York Times as an example of how this “schism” ultimately impacts end users. The Times is considered to be a high quality, trustworthy source of news, and Wikipedia is one of the largest, most comprehensive sources of free information on the web. But, “because the New York Times is for-fee, and because Wikipedia, philosophically, doesn’t like the idea of being tightly embedded with for-fee content, there has developed this kind of bifurcated world,” in which subscription content may receive fewer citations by Wikipedia editors, regardless of the content’s quality. Similarly, he added, “on one side, you have HathiTrust and the Internet Archive doing excellent work making content freely available. And on the other side, you have folks like ProQuest and EBSCO and Gale and Alexander Street making content for fee. And what we thought was, what if we could bring these worlds together? The Open Music Library is a kind of discovery service...that would be unique insofar in that it will bring you not just free content, but for fee content as well." OML is still in development and won’t officially launch until 2017, but the open beta is live at openmusiclibrary.org, allowing interested users to explore OML and join a discussion forum for music researchers and librarians to submit comments, suggestions, and requests. Currently, the OML beta features more than 200,000 digitized scores, 33,000 articles (including paid and open access), and content from more than 100 journals. Alexander Street will continue to build these collections, and also plans to add streaming audio and videos of performances, as well as libretti, ephemera (such as programs and posters from live performances), and possibly an open instrument catalog. Ultimately, the site will also offer an open repository component, enabling registered users to add papers, scores, books, and other content. OML will “provide a really good free index to free content on the web. That’s the starting point, and if we did nothing else, that would be a really good, worthwhile thing,” Rhind-Tutt said. “If we can drive traffic and build a community and have researchers submit content, and allow people that have the wherewithal to pay for the for-fee resources, then we’ll be in an even better situation.” Of course, as a for-profit company, paid subscriptions will be a focus for Alexander Street when OML launches. But the utility of this hybrid model is readily apparent with the field of music research. For example, a very general search for “Bach” using the OML beta currently directs users to hundreds of historical, public domain scores digitized by institutions such as LC and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF) and BNF’s Gallica digital library. But many audio recordings or filmed performances of Bach’s work created in 1923 or later are likely subject to copyright restrictions. OML will enable researchers to navigate both types of content from the same platform. Similarly, users can tab to a search for journal articles about “Bach” and will discover listings and citation information for articles in subscription journals such as Early Music or the Journal of Musicology alongside links to downloadable content from open access publications such as the Journal of the Society of Musicology in Ireland.

Academic database and streaming media publisher Alexander Street is beta testing the Open Music Library (OML), a new online resource that will eschew database paywalls, enabling non-subscribers to discover and use high-quality open access and public domain content from contributors such as the Library of Congress (LC) and the British Library (BL), while offering subscribers a seamless experience discovering and using free and for-fee content together. “Within the marketplace as a whole, there seems to be this almost religious schism between the open access, ‘all information should be free’ advocates and vendors that believe information should be behind a paywall,” said Stephen Rhind-Tutt, president of Alexander Street, a ProQuest company. “Most faculty and students don’t share in that schism. They want the best information, no matter where it’s to be found.” Rhind-Tutt pointed to Wikipedia and the New York Times as an example of how this “schism” ultimately impacts end users. The Times is considered to be a high quality, trustworthy source of news, and Wikipedia is one of the largest, most comprehensive sources of free information on the web. But, “because the New York Times is for-fee, and because Wikipedia, philosophically, doesn’t like the idea of being tightly embedded with for-fee content, there has developed this kind of bifurcated world,” in which subscription content may receive fewer citations by Wikipedia editors, regardless of the content’s quality. Similarly, he added, “on one side, you have HathiTrust and the Internet Archive doing excellent work making content freely available. And on the other side, you have folks like ProQuest and EBSCO and Gale and Alexander Street making content for fee. And what we thought was, what if we could bring these worlds together? The Open Music Library is a kind of discovery service...that would be unique insofar in that it will bring you not just free content, but for fee content as well." OML is still in development and won’t officially launch until 2017, but the open beta is live at openmusiclibrary.org, allowing interested users to explore OML and join a discussion forum for music researchers and librarians to submit comments, suggestions, and requests. Currently, the OML beta features more than 200,000 digitized scores, 33,000 articles (including paid and open access), and content from more than 100 journals. Alexander Street will continue to build these collections, and also plans to add streaming audio and videos of performances, as well as libretti, ephemera (such as programs and posters from live performances), and possibly an open instrument catalog. Ultimately, the site will also offer an open repository component, enabling registered users to add papers, scores, books, and other content. OML will “provide a really good free index to free content on the web. That’s the starting point, and if we did nothing else, that would be a really good, worthwhile thing,” Rhind-Tutt said. “If we can drive traffic and build a community and have researchers submit content, and allow people that have the wherewithal to pay for the for-fee resources, then we’ll be in an even better situation.” Of course, as a for-profit company, paid subscriptions will be a focus for Alexander Street when OML launches. But the utility of this hybrid model is readily apparent with the field of music research. For example, a very general search for “Bach” using the OML beta currently directs users to hundreds of historical, public domain scores digitized by institutions such as LC and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF) and BNF’s Gallica digital library. But many audio recordings or filmed performances of Bach’s work created in 1923 or later are likely subject to copyright restrictions. OML will enable researchers to navigate both types of content from the same platform. Similarly, users can tab to a search for journal articles about “Bach” and will discover listings and citation information for articles in subscription journals such as Early Music or the Journal of Musicology alongside links to downloadable content from open access publications such as the Journal of the Society of Musicology in Ireland.  “The idea behind OML is to provide an experience for the researcher or music student that allows them to find an original manuscript that has been digitized and made available on the web by a national library, and find all of the articles that have been written about that manuscript,” explained André Avorio, head of the Open Music Library Initiative for Alexander Street. “Or, if you find an article that studies a specific performance of an opera, to then go to a video recording of that opera, or to an audio recording of the exact work being discussed in the article. The idea is contextualization [for researchers], and it’s contextualization of a variety of content types that exist in disparate digital collections.” To facilitate discovery of related content across these disparate collections, OML is creating linked open data nodes, much like Wikidata. Using the principles of the semantic web, this structured data enables computers to associate essential information with a specific composer, for example, such as birthplace and a list of works, and then link that specific composer to digitized scores, articles, and other content from Alexander Street as well as content in the digital collections of different institutions. This structure should make it straightforward to add more public domain resources as OML grows. The OML database “defines individuals, it defines metaworks, and it defines instantiations of those metaworks,” explained Rhind-Tutt. “An example of a metawork might be [Ludwig van] Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. There are many instantiations of Beethoven’s 9th—there might be a video, there might be an audio recording, there might be a score, there might be combinations of those things. So…we took the backbone of this semantic structure, and started attaching various works to it.” In addition to BL, BNF, and LC mentioned above, other major third-party contributors currently include Denmark’s Royal Library, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, and Poland’s Biblioteka Narodowa and POLONA digital library. While working with open linked data projects such as Wikidata is certainly in the interest of institutions that want content from digitized collections to surface in open web searches, Avorio noted that the OML platform serves a much different purpose than a Google search, and explained why it will be a particular benefit for institutions to partner with OML on music collections. "The more [linked data] initiatives the better," he said. "Because Wikidata, just like Wikipedia, they help address the challenge of discoverability.... Wikipedia is part of the [Virtual International Authority File] network, and therefore, we can go from a Wikipedia page to an OML composer to all of the scores that exist in all of the national libraries...authored by that composer." The difference, he explained, is that OML will provide a free discovery layer for academic content about music. "The audience of Wikidata, just like the audience of Wikipedia, is generic, and includes people from virtually all domains," he said. " Whereas the audience of the Open Music Library [will be] centered around academic music and the academic music community—music scholars, music researchers, music professors, music teachers, music students, performers, artists, composers. The core difference is the specificity of the audience." And Avorio envisions the OML as a platform that will ultimately help researchers make discoveries beyond content, "potentially a platform for data analysis. So, if you think about social network analysis—and the importance of collaboration networks in the study of music—I want to know who collaborated with whom, and what did they produce, when? How did the mentorship network actually emerge? These are all things that researchers will be able to do once we have combined enough available structured data within the platform."

“The idea behind OML is to provide an experience for the researcher or music student that allows them to find an original manuscript that has been digitized and made available on the web by a national library, and find all of the articles that have been written about that manuscript,” explained André Avorio, head of the Open Music Library Initiative for Alexander Street. “Or, if you find an article that studies a specific performance of an opera, to then go to a video recording of that opera, or to an audio recording of the exact work being discussed in the article. The idea is contextualization [for researchers], and it’s contextualization of a variety of content types that exist in disparate digital collections.” To facilitate discovery of related content across these disparate collections, OML is creating linked open data nodes, much like Wikidata. Using the principles of the semantic web, this structured data enables computers to associate essential information with a specific composer, for example, such as birthplace and a list of works, and then link that specific composer to digitized scores, articles, and other content from Alexander Street as well as content in the digital collections of different institutions. This structure should make it straightforward to add more public domain resources as OML grows. The OML database “defines individuals, it defines metaworks, and it defines instantiations of those metaworks,” explained Rhind-Tutt. “An example of a metawork might be [Ludwig van] Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. There are many instantiations of Beethoven’s 9th—there might be a video, there might be an audio recording, there might be a score, there might be combinations of those things. So…we took the backbone of this semantic structure, and started attaching various works to it.” In addition to BL, BNF, and LC mentioned above, other major third-party contributors currently include Denmark’s Royal Library, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, and Poland’s Biblioteka Narodowa and POLONA digital library. While working with open linked data projects such as Wikidata is certainly in the interest of institutions that want content from digitized collections to surface in open web searches, Avorio noted that the OML platform serves a much different purpose than a Google search, and explained why it will be a particular benefit for institutions to partner with OML on music collections. "The more [linked data] initiatives the better," he said. "Because Wikidata, just like Wikipedia, they help address the challenge of discoverability.... Wikipedia is part of the [Virtual International Authority File] network, and therefore, we can go from a Wikipedia page to an OML composer to all of the scores that exist in all of the national libraries...authored by that composer." The difference, he explained, is that OML will provide a free discovery layer for academic content about music. "The audience of Wikidata, just like the audience of Wikipedia, is generic, and includes people from virtually all domains," he said. " Whereas the audience of the Open Music Library [will be] centered around academic music and the academic music community—music scholars, music researchers, music professors, music teachers, music students, performers, artists, composers. The core difference is the specificity of the audience." And Avorio envisions the OML as a platform that will ultimately help researchers make discoveries beyond content, "potentially a platform for data analysis. So, if you think about social network analysis—and the importance of collaboration networks in the study of music—I want to know who collaborated with whom, and what did they produce, when? How did the mentorship network actually emerge? These are all things that researchers will be able to do once we have combined enough available structured data within the platform." RELATED

RECOMMENDED

TECHNOLOGY

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!