Library School Students Master Original Research

Long a mainstay of LIS professors, who advance the field with their examination of learning behaviors and library praxis, increasingly such discoveries are part of the learning experience for students as well.

RESEARCH AND LIBRARY SCHOOL go hand in hand. By the time library or information school students graduate, they’re veterans at researching topics—figuring out which kinds of resources will be germane and trustworthy, finding them in-house or out. But a different kind of research is also a part of library school: original research conducted by students and faculty. Long a mainstay of LIS professors, who advance the field with their examination of learning behaviors and library praxis, increasingly such new discoveries are part of the learning experience for students as well.

LJ took a look at work being done nationwide and spoke with some of those involved to get an overview of what’s under investigation, how students encounter the process, what they get out of it at the time (from course credit to prestigious publications), and how it benefits their later careers, whether they stay in academia or not.

Such research is amazingly varied, including the highly theoretical as well as more practical efforts to improve a specific area of library activity. Taking note of the hottest trends in student research topics highlights areas of rapid change in the field, pain points in library practice, and gaps in the existing literature.

Technology is a common thread in many current studies. At a broad level, it’s even possible to say that most research now involves looking at the use of technology in one way or another. Under that umbrella, however, two themes emerge as hot: user privacy and the use of open educational resources (OER). How to improve and encourage patron ease of using the library and its resources is also being explored.

EXAMINING PRIVACY

Student projects completed at New York City’s Pratt Institute offer a look at a variety of privacy-related studies at the master’s level, with recent efforts including “The Role of Libraries Within Prisons, Jails, and Juvenile Facilities” and “Mapping Lab: 2016 Stop and Frisk Data in Carto.” Geographic information system (GIS) and mapping tools such as Carto and other data analysis and display tools are heavily used by today’s students, who are expected to be adept at informatics. (In addition to traditional research papers, many projects are publishing their underlying data sets and producing data visualizations.)

“We feel strongly that a master’s program is not about skills but about deep understanding of theories and contextualizing theory in the workplace,” says Debbie Rabina, professor and LIS program coordinator at Pratt. “While skills address the how, research provides an answer to the why. It is not possible to be a leader in the field without understanding and engaging in the research process. Original research is obviously challenging within a semester framework but not uncommon. We see original research especially from students [whose projects] combine technology and literature.”

One Pratt student project that combines technology and not literature but media is "An Educator’s Guide to Internet Privacy Using Mr. Robot." In this 2016 work, Pratt MSLIS candidate Allison Nellis created a guide to be used with adults who are learning about technology-related privacy in the library or classroom. It employs as a basis the first season of the cable television series Mr. Robot, whose main character is an engineer at a cybersecurity firm. The guide discusses privacy issues that appear throughout the series, pinpoints specific laws that are broken in each episode, and provides talking points for classroom discussion. This guide presents an unusual method of study for students probing privacy and cybersecurity legislation.

OPENING THE BOOKS

One OER research project has recently been started by Elizabeth Dill, director of library services at Troy University, AL, who is pursuing a doctorate in public administration (DPA). (It is worth noting that not all work assessing library practice happens in library schools.) Dill is assessing academic library value using the bibliographies of Troy’s grant applications. Her work will compare the number of citations to materials in Troy’s library e-collections to the number of citations to OER and open access (OA) resources. The research will also examine the amount of grant money awarded according to citation type. Dill explains that the “findings can help academic library administrators make and justify informed decisions regarding budget allocation for their online collections. Also, as this is a three-year study, the yearly number and percentage of increase or decrease over the prior year for each type of resource will be determined.”

Related investigations have been performed in the past, and Dill says that work was the impetus for her study. “Work has been done before that looked at the ROI [return on investment] on [our] library’s collections, and I wanted to expand upon that to look at OER,” says Dill. “I’ve never done original research before, so I’m learning as I go through the DPA program. I think this will be valuable research for my institution because we’re trying to get as many grants as possible.”

Dill notes that her long-term goal is to progress through the ranks of library administration and considers research work an important step toward that goal. “It is important to my career to have this experience under my belt,” says Dill. “The plan is for it to lead to a job as assistant or associate dean in the future."

TWO KINDS OF DATA (l.–r.): The Making in Michigan Libraries Virtual Conference reported out student findings from the University of Michigan; this eye-catching graphic highlighted Pratt student research into the role of libraries in prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities

ASSESSING USER EDUCATION

Like OA, helping patrons acquire or improve information literacy and ease of use of the library is hardly a novel concept, but new aspects of the problem appear as technology, libraries, and patron needs and expectations change. Fresh ways of tackling the issue are always welcome, making this a lively as well as perennial area of research work.

Student Ben Rearick has been working for one and a half years at the University of Michigan (UM) Libraries on the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS)–funded project “Making in Michigan Libraries.” The project involves teaching local public librarians about Maker spaces, the Maker movement, and how they can implement Maker activities in their community. The researchers seek information on how libraries view the Maker movement and what their communities require from it, whether the need is education, help for entrepreneurs, or, says Rearick, “just providing a place for children and adults to relax.” The team is creating a Maker space handbook for libraries; it has already held a related virtual conference.

Another aspect of the grant is researching the implementation of Maker curricula. “In the public libraries we’re involved with, we’ve worked with after-school programs, and so we’ve been able to test out curricula and see what students are interested in, how they learn, and what works,” comments Rearick.

Rearick sheds some light on what it was like to enter an ongoing project, something many students face as they join a multiyear project for a semester. “I came into this work while it was already under way,” he explains, “so I’ve had to work out what was already done with the handbook and the direction it was going in before. I’ve had to work with my professor on what to focus on in the handbook and what sort of voice it should have.” Like Dill, he emphasizes that the completion of research in library school is career-boosting. “I’ve been able to present at a couple of conferences, reporting on what I’ve done,” says Rearick. “Having a publication and having presented, even at an event as small as the research symposium that’s built into the grant, is a demonstration of being able to conduct research in an academic library setting, which I hope to do in the future.”

STUDYING FIRST-GENERATION STUDENTS

The information literacy needs of first-year students are the subject of an upcoming research project at the University of Alberta (UA), Edmonton, and of recent work at the iSchool at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Jen Kendall is a graduate research assistant at the UA SLIS and an intern for the university press. She is beginning research about first-year students’ anxiety when it comes to libraries, with students at her university as the subjects. “I am hoping to compare how first-generation students (FGS) compare to continuing generation students (CGS) when taking a modified Library Anxiety Scale (LAS) as well as interviewing several FGS to learn more about how they experience library anxiety,” Kendall says. “Much research has been done on library anxiety, and FGS are becoming more visible as their presence in academia increases, but little research has been completed on how library anxiety specifically manifests in these students.”

Her choice of subject was informed by her own history. “As an FGS,” says Kendall, “I had many of the [exposures]that my first-generation peers have had. When I was seeking a topic for a preliminary research project...I discovered that not only were we generally overlooked in the literature, but our specific anxiety about navigating academic libraries was largely overlooked (an exception being Ernesto Hernandez Jr., at Weber State University, Ogden, UT, who was kind enough to share some sources with me and offer support).”

Kendall decided to learn more “in order to, at minimum, compile a resource guide to help other students in my position. University is stressful enough without thinking you’re the only person in the room who doesn’t understand what’s happening.” The results of the study will benefit academic librarians’ practice, Kendall says, by showing them ways in which FGS feel uncomfortable both in the library and in navigating libraries’ digital resources. Public libraries will benefit, too, with Kendall noting that “FGS are more likely to use the public library while in university for a variety of reasons: accessibility, comfort, free parking, ability to bring children, extended hours.”

TEACHING THE RESEARCHERS

Related work at the University of Illinois (UI) was completed in fall 2017 by a team led by Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe, professor/coordinator for information literacy services and instruction in the university library. “We often think of library school students as getting practical experience in being a librarian,” Hinchliffe says, “but I’ve been doing a lot of work with library school students who anticipate that they want to go into academic library jobs, where they will be tenure track and will need to do research and publish.”

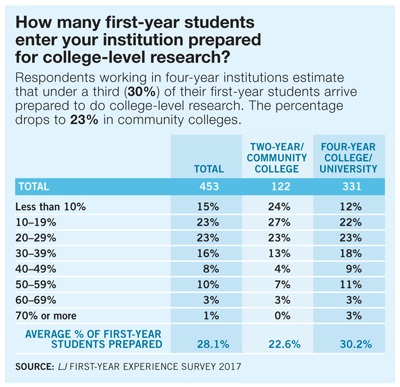

Hinchliffe’s fall 2017 team investigated the misconceptions that first-year students have related to information literacy. They used survey data collected by LJ reflecting librarians’ opinions of and encounters with first-year students, then coded the librarians’ responses in order to identify misconceptions on the part of students. The team then took that misconception inventory and held focus groups with librarians who work with first-year students, says Hinchliffe, validating and modifying the misconception inventory with group feedback. (Follow this link for a webinar about this project.) “Some of the results are not surprising,” says Hinchliffe. “For example, we found that first-year students believe that Google is sufficient for academic research and that they are already information literate.”

Hinchliffe explains that in her work, she aims to help students who want to go into academic libraries, where they will have research responsibilities, to be prepared by developing their research skills and knowledge. “Some of the biggest challenges for those who are new to carrying out research is that the processes...are very opaque,” she notes. “To people who are new to the research process, it looks like there’s this question, then a bunch of miracles occur, then an article gets published.” She’s working to demystify the process and help students see that doing research involves skills and knowledge but also project management know-how.

In Hinchliffe’s role with student researchers, which she refers to as “coaching and mentoring,” she is careful to set expectations that work with students’ schedules. “It’s not possible to do a research project and get it published in one semester,” she says, “so it would be unreasonable to make getting published a required outcome to a good grade. And the research might not go well. Publication space is competitive, and you have to show why your research matters.” Typically, Hinchliffe says, she requires students to complete the project, reflect on the process in writing along the way, and write a summative essay at the end. Then, depending on the student and the topic, she might also ask them to write a conference proposal but doesn’t require that it is actually submitted, because the student may not have the funding or other capacity to attend if accepted.

Allison Rand, a graduate assistant in the undergraduate library at UI, participated in Hinchliffe’s project on first-year students’ misconceptions and offered a student-researcher perspective. “This research has a lot of layers,” she says. “We are trying to understand how librarians understand how first-year students understand the library.” Rand illustrates how, sometimes, research findings cause a pivot in a project’s approach. “We initially threw out affective data like ‘the students don’t want to be here,’ because it wasn’t what we were studying,” says Rand. “But as we continued with the work, we discovered that the misconceptions that we were finding were the reasons behind the affective problems. So the things we threw out at the beginning of the research came back in at the end.”

Rand’s goals were to learn about the research process and get some familiarity, she says, noting that “this is kind of a vague plan for a for-credit independent study, but I didn’t want to make my goals too specific because I didn’t know how in-depth the research would be. It turned out that I ended up with two deliverables from the work: the paper that I wrote up as part of the independent study and the one the other researchers and I wrote as a team.”

She explains that a less-tangible but valuable outcome of the work relates to academic job seeking. “Since [the MLS] is a terminal and a professional degree, there is some pressure that you should come out of library school able to do this kind of work,” Rand says. “Looking at job ads, I see that I can already check off several boxes. [Employers can see that] I have this drive to publish and be involved in the academic community.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!