Small Strategies: Wearing Many Hats in Small Academic Libraries

Reference librarians in small academic libraries do a little of everything, from seeing synergies to creating workarounds for staff, collection, facilities, and budget gaps.

Reference librarians in small academic libraries do a little of everything, from seeing synergies to creating workarounds for staff, collection, facilities, and budget gaps

Last summer, Library Journal checked in with reference librarians at small academic libraries. Themes that emerged from these conversations were the challenges of limited resources and the unique opportunities that exist in a smaller organization.

WEARING MANY HATS

“Working in a small library means you need to be nimble and agile,” says Stephanie Davis-Kahl, university librarian and copyright officer at Illinois Wesleyan University’s Ames Library (1,600 enrollment). “We all do a little bit of everything, which means it’s easy to see connections and intersections between our various responsibilities.”

Sharon Spence-Wilcox, a reference and instruction librarian at Seattle Central College (SCC) (4,782 full-time equivalency enrollment), noticed a shift with the arrival of a library dean who made “strong moves to break down silos and bring us together,” as well as increased worker democratization. Spence-Wilcox and her coworkers are cross-trained to provide backup coverage at the circulation desk. Work on library displays and outreach at campus events rotates through all staff. Spence-Wilcox says that this collaborative staffing model is “a welcome change from my early days [at SCC] where the approach was, ‘Only librarians do that.’ ”

As evidenced by her multiple job titles, Deborah Tritt Harmon, instruction and reference librarian, archivist, and associate professor at the University of South Carolina (USC) Aiken (3,522 enrollment), wears many hats. “In contrast to a large institution, there is less of the ‘stay in your lane’ mentality,” Harmon states. “If you see an opportunity to begin an initiative or fix something that’s not in line with your normal duties, it is often all right.”

|

SMALL WONDERS University of South Carolina Aiken’s Gregg-Graniteville Library enjoys a student-centered approach to services. Photo courtesy of Gregg-Graniteville Library |

SMALL LIBRARIES, LIMITED STAFF

Cross-training not only builds competence but is often necessary owing to budgetary limitations on staffing. This has never been more evident than during the COVID pandemic. Libraries have had to flex around workers being out for extended periods and staff positions being cut or not filled. “Two of our three missing staff people were in technical services,” says Becky Canovan, assistant director of public services at Iowa’s University of Dubuque Charles C. Myers Library (2,026 enrollment), “and they were the people already cross-trained to cover each other’s jobs. Because these two jobs were necessary to keep the library running day-to-day…three of us on the public services team had to jump in to cover these tasks.” Canovan, awaiting the time when the budget allows for the rehire, has also been assisting with the tasks of the vacant library direc-tor position. “Sometimes it’s hard to remember what it’s like to just have my own job.”

The open hours of small academic libraries are directly tied to available staffing. “Our Saturday and weekday hours had to be cut,” says Spence-Wilcox. “During summer quarters, evening students are at a complete disadvantage as our library closes at 4 p.m. Students in ESL and refugee programs especially suffer from not being able to visit and access materials.” At SCC, concerns around access have helped spur an ongoing initiative to train all library staff in equitable and inclusive approaches to the services they offer. Spence-Wilcox emphasizes that library workers have all participated in a series of trainings on creating an anti-racist library. “We are becoming more aware of the institutional racism that has existed in our spaces and how we can examine the status quo, ask questions, and adjust our lens as a united front to dismantle the systems of oppression our students experience,” she says.

Like larger institutions, libraries in smaller colleges and universities use student employees to cover workflows and tasks. In a smaller library, though, these students may provide much more critical coverage. “We lean on our student workers to fill in when staffing freezes or gaps between hirings occur,” notes Canovan. “Giving students the opportunity for challenge has resulted in two of our former student workers being hired on as professional staff upon graduation, and three student workers and two paraprofessional library staff members have gone on to get library degrees.”

While usage has declined in recent years, pre-pandemic the library was “extremely busy” during the day, says Spence-Wilcox. “We relied heavily on reference assistance from [the University of Washington’s iSchool] and other graduate programs to support the full- and part-time library faculty at the help desk.” SCC’s own work-study program supports circulation tasks, with student workers providing materials checkout services, along with shelving and inventory duties and the processing of new books.

|

Seattle Central College Library offers a variety of experiences for staff cross-trained in a range of roles. Photo courtesty of Sharon Spence-Wilcox |

COLLECTIONS IN FLUX

Making the most out of a tight materials budget is standard procedure in small academic libraries. Brandy Horne, reference and instruction librarian, coordinator of library instruction and reference, and associate professor at USC Aiken, says that state funding for public colleges and universities is already low, “and ours has been under 15 percent for over a decade.” The library hasn’t had a budget increase in more than 10 years, Horne says, despite the rising costs of materials. “During COVID, we froze our print materials budget, and we cut several databases,” some of which are slowly being added back as funding allows.

“Our book and media budget has never been enough to cover the needs of our instructional programs,” notes Spence-Wilcox. “Periodicals and database costs have skyrocketed to the point where we had to end subscriptions.” She and her colleagues find creative ways to connect SCC students with needed information. For example, interlibrary loan (ILL) and document-delivery services supplement SCC’s own collections, and the library often refers students to the University of Washington’s library system or the local public library.

|

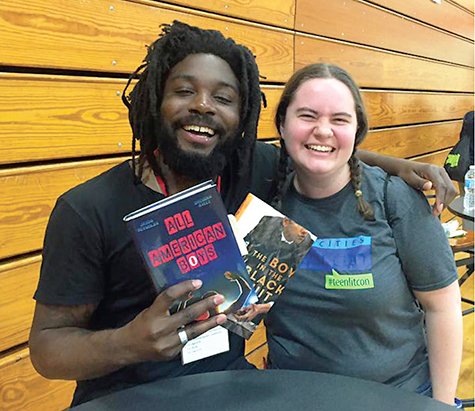

Becky Canovan (r.), assistant director of public services at Iowa’s University of Dubuque Charles C. Myers Library, with author Jason Reynolds after his participation in her library book club. Photo courtesy of Becky Canovan |

FACILITIES CHALLENGES

As student populations grow, these librarians are working to overcome barriers presented by the limits of their physical location. “Over the years, as the student population and use of the library has grown, we’ve been forced to downsize our book collections and remove shelving to make way for more seating,” says Spence-Wilcox. “Students’ needs for both quiet and collaborative spaces are difficult to satisfy.”

At the USC Aiken library, the entirety of the print periodicals collection was removed “to make space for learning commons,” according to Horne. The change in layout and the loss of those periodicals now means there is space for tutoring, advising, and student media creation. “Our library has been requesting funding for library renovations from the legislature every year for the last decade,” she says. “Our instruction room is small and outdated, with only 22 computers, so larger classes cannot be accommodated.”

Providing appropriate, modern spaces for students is also a challenge for Cali Biaggi, online learning librarian with Doane University’s Perkins Library in Crete, NE (enrollment 2,060). Biaggi notes that the library’s largest conference room was recently assigned to another campus office, “despite a lot of fighting against that happening. Something that may have helped in that situation would have been presenting better data about space usage,” but it all comes back to limited staff not having the time to work on such data-driven projects.

CREATIVITY AND COLLABORATION

Despite the barriers of time, staff, and space limitations, these librarians deliver exciting programs and projects that deepen the connection among the library, faculty, and student body. Canovan notes that there was a “particularly loud chorus of ‘students don’t read’ ” on campus. To counter this perspective, she helped run a young-adult book club for several years at the Myers Library. The book club leaders sought high-profile, popular titles that engaged dozens of people each session. Canovan found affordable copies of the books online and utilized ILL services to pull in additional copies. Club meetings included author presentations done via video calls and phone chats. “My favorite marker of success was handing an autographed and personalized copy of All American Boys [by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely] to a student who said that reading the book had changed him.”

Escape room–style programs intrigued Biaggi, and while she didn’t have the time or budget to go all-in on an instruction-based version of one, she crafted an activity using Google Forms. Each question on the form was a clue for students to solve to advance through the puzzle. “The clues were designed to get students to practice simple research-related tasks, [such as] searching the online catalog, searching a database, using a LibGuide, and using ILL services.” Biaggi’s first run was such a hit with a summer bridge program that she moved on to use the electronic scavenger hunt as an introduction to the library for all first-year students.

At USC Aiken, Harmon says, “Years ago, we noted that our students were struggling with the fundamentals of citation and that no single entity on campus was providing any support.” To address this concern, the library developed a series of simple style-guide handouts and moved on to creating YouTube tutorials. A video on APA 7th edition citations had 227,723 views as of the end of May. “Defining our success is the continued growth of citation-related initiatives,” says Harmon. The library developed inroads with nursing faculty, as well as the engineering and business disciplines that previously had low engagement with the library. “We have built authority, and our community knows and trusts our expertise,” Harmon continues.

In 2020, Davis-Kahl’s library transitioned to a new ILS along with more than 125 academic and special libraries in Illinois’s Consortium of Academic and Research Libraries, which serves over 90 percent of the state’s higher-education students, faculty, and staff. “The amount of work that went into a clean implementation [of the new ILS] is nothing less than extraordinary,” she notes. This was made more challenging by pandemic-related remote schedules and increased caretaking roles for many workers. “I’m lucky to work with a group of librarians and staff who have students foremost in mind, and who work together to do whatever work is before us, whether it’s moving many, many chairs to storage for social distancing, or learning how to be a backup for another person or learning a new technology.”

It’s this can-do attitude that bands small academic librarians together, working to achieve goals and innovate solutions despite challenges.

April Witteveen is the library director at Oregon State University’s Cascades campus.

Add Comment :-

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing